Bernice Bing: Women’s Caucus for Art 1996, Excerpt from Ceremony by Flo Wong

WOMEN’S CAUCUS FOR ART 1996

Honor Award Ceremony

an excerpt from the presentation ceremony

By Flo Wong

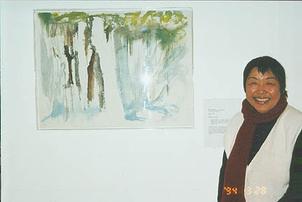

There is nothing more challenging to us as human beings than to embark on the path of self-enlightenment. Throughout her life, tonight’s honoree has done this admirably. It is with great honor that I introduce Bernice Lee Bing–artist and activist–who has courageously searched for self-enlightenment through a life of creativity and community commitment.

To highlight Bing’s life and art, I quote from the Tao Te Ching by Lao Tsu who taught about life and spirituality in ancient China 2,500 years ago. For me, Bing’s life and art exemplify the Tao which means THE WAY. Simply stated, it addresses a possible inner greatness and an equally possible inner failure.

In 1989, I met Bing in Oakland, California at an Asian American Women Artists Association meeting. When I first saw Bing’s paintings. I was overwhelmed with her masterful strokes, rich colors, glowing light and fluid, organic shapes. Her art made me hear cymbals of silence; I was immediately whisked into her artistic milieu.

At the time. I was project director for an exhibition entitled Completing the Circle: Six Artists featuring Northern California-based American artists of Chinese descent. This was intended to travel to China: its goal, to introduce contemporary Chinese American artists to the ancestral homeland.

Bing was accepted into the exhibition for her powerful abstract paintings expressing visual intersections of East and West. Raging Wind, an oil painting created in 1986, reveals what art writer Valerie Soe calls Bing’s intuitive process of the subconscious mind. Soe notes that Bing’s “Sweeping lines and splashes of paint on canvas evocatively spoke of Abstract Expressionism, Chinese calligraphy and painting.” Her strong and personal art revealed an aesthetic search for light within the dark metaphor of the Tao’s teaching.

Bing was born in San Francisco’s Chinatown in 1936, when immigration from China was still restricted by the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Law. Her mother had married when she was eighteen. Although she was a wife and mother, she wanted a glamorous life beyond domesticity and worked at Shanghai Low, a popular Chinatown night club when Bing was a child.

When Bing was six years old her American-born mother died of a heart ailment. After her mother’s death, Bing lived in Caucasian foster homes, occasionally staying with her grandmother. Bing’s movement in two disparate worlds–Chinese and American–had begun.

Bing’s bound-feet grandmother, traditional, subservient and angry, was abusive to Bing. And Bing was rebellious. She had difficulty assimilating at a middle class white school and did not do well academically. But drew to fill her time.

When Bing was seven, her art caught her grandmother’s attention and she frequently praised Bing’s emerging talent. Thus began Bing’s realization that art would be the means to understand her two cultures. Bing subsequently found her voice in life–and it has stayed with her ever since.

Through art, Bing dealt with the remoteness of her family and life set in a transplanted culture and the non-Asian world she encountered.

In 1958, she attended California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland on a scholarship, studying with Nathan Oliveira, Saburo Hasegawa and Richard Diebenkorn. Under the tutelage of Hasegawa she blossomed, switching her major from advertising to painting. Hasegawa’s use of Zen meditation in his dreamy-abstract and calligraphic art captured her attention.

Bing considering what it meant to be an Asian woman in America, pursued the poetry of Lao Tsu and other Eastern philosophers to learn more about her self, family and history. To this day, the spirituality of Eastern metaphysical thought informs her work.

After a semester at California College of Arts and Crafts, Bing transferred to the San Francisco Art Institute where she studied painting with Elmer Bischoff and Frank Lobdell. It was a time of the avant-garde. Bing’s artistic mentors were varied. Among them were de Kooning in art, Stein in poetry, Camus in literature, Beckett in theater and Fellini in art films.

In 1961, Bing graduated from the San Francisco Art Institute with a Masters in Fine Arts degree. She painted Blue Light in the same year, with a red ideogram, which in Chinese means people or humanity, in the bottom left corner. There is also a suggested shape of a heart. Both symbols–humanity and heart–reflect Bing. They direct me to chapter ten of the Tao which reads:

Understanding and Being open to all things,

Are you able to do nothing?

Bing did something.

Following her graduation, Bing was active in the Bay Area art scene. She had befriended Joan Brown and accompanied Brown in 1960 to New York for Brown’s first one-person exhibition. In New York, Bing met Marcel Duchamp.

In California, exhibiting locally in San Francisco and Berkeley, she received critical acclaim. Alfred Frankenstein, critic for the San Francisco Chronicle, noted Bing’s remarkable gift for the fluid line. Bing’s remarkable fluid lines are still strong after thirty years of painting.

In 1961, Bing worked as a caretaker at Mayacamas Vineyard in Napa Valley, where she experienced first-hand the power of nature. For Bing, nature was tactile and captivatingly spiritual. As a resident artist at Esalen in 1967, she was among the first to study New Age psychology and philosophy with Abraham H. Maslow, Joseph Campbell, Alan Watts, Ronald D. Laing and Fritz Perls.

It was an eye opening time for Bing. At Esalen, she concentrated on learning about her self through psychological and philosophical studies.

It was trail-blazing for Bing to depart from her traditional culture which emphasized family over a sense of self.

In 1968, Bing served on a National Endowment for the Arts panel for the Arts expansion program. In the early 1970s , she organized art events and programs in San Francisco. Among her achievements was establishing the first Asian American Art Festival at the SF Civic Center.

During a violent phase in Chinatown when killings were rampant. Bing established an art workshop with the Baby Wah Chings, a Chinatown gang. That program gave eleven to thirteen year olds a place to channel their energies. For those efforts, Bing won recognition. In 1983, she received the Distinguished Alumni Award from the San Francisco Art Institute. In 1984, Bing was awarded the SF Art Commission Award for Distinguished Work and Achievement in Community Arts. From 1980-1984, she directed and established innovative programs at the South of Market Cultural Center.

Her creative energy depleted, she renewed her life with a stay in China–the home of her ancestors–as well as Korea and Japan. In China she studied calligraphy and painting at the Zhejiang Academy in Haungzhou. And she lectured on Abstract Expressionism, helping Chinese art students understand the world of art.

Refueled and rested, she returned to the United States and settled in rural Philo in Northern California to begin art-making anew. Vital Energy, a 1986 oil painting, talks about the lifeblood of creating after an absence. In 1990, Bing received the Asian Heritage Council Art Award in recognition of her talent and her pioneering efforts to serve the art and Chinese American cultural communities in San Francisco.

Bing’s paintings from the late 1980s and early 1990s illustrate the unspoken heritage of her training grounded in Abstract Expressionism. They also portray Bing’s painterly calligraphic synthesis of the old world of China. The impasto of the paint comes from the buildup of calligraphic lines. Lotus Root , 1992, oil on canvas, refers to opening up with her Quantum Series Bing represents realms of possibility. She is still exploring the mystery of how small elements become a part of the whole.

In her life, Bing has discovered that art provided unity between her dual cultures. For her, virtue and perseverance are abundant.

It is with great honor that I present the distinguished Bernice Lee Bing. Through dedication to art and activism, Bing has walked the path of self-enlightenment.

“Knowing the self is enlightenment.”

Tao Te Ching, chapter thirty-three