Acting Out: Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore

Acting Out: Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore

April 4, 2005 – July 2005

The Judah L. Magnes Museum

2911 Russell Street

Berkeley, CA 94705

Gallery Hours: Sun-Wed 11-4, Th 11-8

An exhibition to present the little-known chapter in the lives of the famed Surrealist photographer Lucie Schwob (aka Claude Cahun) and her partner, the writer and artist Marcel Moore.

In the 1930s, Cahun and Moore participated in a range of anti-fascist activities. In 1937, they left Paris for the Isle of Jersey. When the Island was occupied during WWII Cahun and Moore were imprisoned for acts of resistance. Their house was commandeered by German troops who looted its contents, dispersing the library and destroying many of the artworks and photographs found on the premises. Despite the fact that what Cahun characterized as “the best of the work” then perished, an intriguing photographic and documentary legacy survived at the Jersey Historical Trust (UK).

Dr. Tirza True Latimer, Guest Curator.

Acting Out: Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore

remains on display at The Judah L. Magnes Museum until July 31, 2005

The exhibition is made possible through a generous grant from the Walter and Elise Haas Fund along with additional support from the Consulat General de France a San Francisco.

Acting Out: Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore

Acting Out, guest curated by Dr. Tirza True Latimer, differs from previous exhibitions featuring photographs of the Paris surrealist Claude Cahun in at least two significant aspects. First, the exhibition spotlights the collaborative dimension of an oeuvre conventionally attributed to Cahun alone. Many of the photographs described in recent catalogues and exhibitions as “self-portraits” were actually shot by Cahun’s life-long partner, Marcel Moore, who alternated positions with her lover before and behind the camera’s lens. Secondly, Acting Out situates this body of work with respect avant-garde theater in Paris, where Cahun and Moore were both spectators and performers throughout the 1920s. This significant context has been upstaged in recent scholarship by the later surrealist affiliation. Acting Out aims, then, to fill in the theatrical backdrop against which Cahun’s photographic episodes were staged while restoring Moore to the scene of their production.

The exhibition showcases approximately 90 objects including estate prints of photographs featuring Cahun, as well as high quality facsimiles of Moore’s costume and set designs, publications realized by the two artists working in collaboration, and personal documents. This material offers dramatic documentation of the couple’s cultural and political engagements, from Paris’ experimental theater of the 1920s to acts of resistance staged during the German Occupation of Jersey (where Cahun and Moore had taken up residence in 1937). The Jersey Heritage Trust collection, from which the exhibition is drawn, contains works unknown to US audiences. By juxtaposing unfamiliar images produced by Cahun and Moore with newly translated excerpts from Cahun’s writings and by considering the couple’s cultural activities from fresh perspectives, Acting Out aims to incite a new round of discussion and scholarship.

Acting Out: Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore

By Tirza True Latimer

“Photography is a kind of primitive theater, a kind of tableau vivant,” Roland Barthes remarked, shifting attention away from the medium’s significance as an evolutionary event in the history of pictorial representation.1 Viewing photography in this way, as a dramatic art, enables us to think about the photograph as an arena in which to act rather than a stilled frame out of reality’s filmic continuum. Since theatrical performance invariably requires an audience, looking at photography through the lens that Barthes proposes brings the spectator’s role in the production of meaning into focus. This, in turn, opens new realms of insight into a range of photographic as well as theatrical practices and has specific applications with respect to the work generated by Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore in the early twentieth century.

The photographic oeuvre featuring Cahun has earned acclaim and circulated in contemporary shows and publications under the banner of “self-portraiture.” I take exception to this classification on several counts. Hardly anyone would deny that these images result from some sort of collaboration, since Cahun could not possibly have realized most of them without assistance. This observation alone suffices to compromise the word “self” in the generally accepted formulation “self-portraiture.” Yet the categorical designation has provided scholars, curators, and other viewers with what seems a viable term of convenience. A number of art historians have compared Cahun’s photographic tableaux to those of the contemporary artist Cindy Sherman–who engages assistants to produce the photographic compositions that she enacts and/or envisions.2 While the designation “self-portraiture” unquestionably elides important aspects of Sherman’s representational process and project, framing the collaborative work done by Cahun and Moore as self-portraiture has additional consequences. Cahun’s collaborator, after all, was not a professional assistant but her life-long mate, Moore. What social prejudices and artistic hierarchies does the erasure of Moore accommodate and to what extent did the two artists foresee, forestall, foreclose (or, on the contrary, foreordain) this erasure?

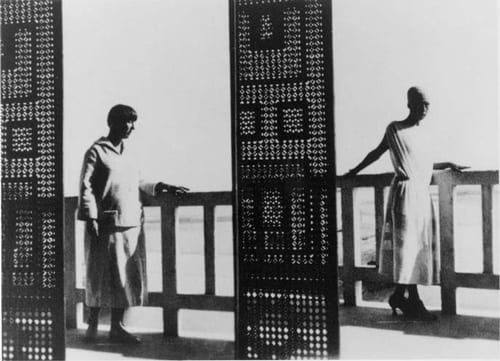

Let us look for answers–that is to say, statements of or about co-production–in the work itself. The Jersey Heritage Trust collection (featured in the current exhibition “Acting Out”) preserves numerous negatives and prints that make both the fact and the thematic of collaboration apparent. Some shots, for example, picture first Cahun and then Moore posing alternately in the same setting [figs.1-2, JHT/1995/41/n and JHT/1995/24/h].

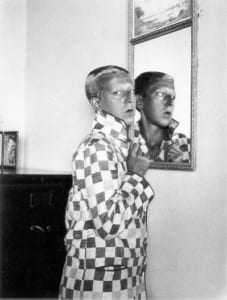

In addition to these reversals, the device of doubling and other metaphorical and formal references to artistic and emotional complicity–such as the intrusion of the photographer’s shadow upon the space of the photograph–affirm Moore’s engagement in less literal ways. A photograph, taken circa 1915 [fig. 3, JHT/1995/15/m], representing the still adolescent-looking Cahun posing against a massive formation of granite offers a case in point. We see Moore’s shadow cast upon the scene (and upon the photographic paper) in the lower right hand corner of the composition–just where we are conditioned to look for the artist’s signature. This doubly indexical mark could be understood as a sort of artistic contract that the couple would honor for nearly forty years. The silhouette, which draws the photographer/viewer into the frame of the picture, allows us to imagine the sitter’s expressive acts coming to fruition in the eyes of an unseen but present observer to whom those gestures are addressed.

At the very least, it would seem expedient to remove the hyphenated “self” from the label “self-portraiture” and to reconceive of portraiture, like photography, as a theatrical pursuit. Certainly portraiture, as practiced by Cahun and Moore, performed something other than the traditional functions of commemoration or classification. It appears to have served, on the contrary, to destabilize the notion of “self” that the portrait genre has historically upheld–and, more constructively, to provide an arena of experimentation within which the photographer and the subject could improvise alternate scenarios of social, sexual, and artistic practice. Within this arena, Cahun and Moore–subject to the constraints that faced “the weaker sex” in patriarchal societies in their time–could act up, act out, enact their desires, and act upon their convictions.

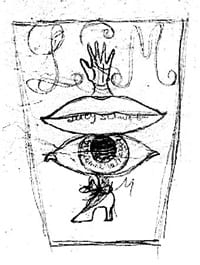

The creative alliance between Cahun and Moore formed in provincial Nantes, where, in 1909, the fifteen-year-old Lucie Schwob (who would later adopt the pen name Claude Cahun) encountered the seventeen-year-old beaux-arts student Suzanne Malherbe (Marcel Moore) in what they both described as “une rencontre foudroyante.”4 Eight years later, Cahun’s father, Maurice Schwob, a prominent publisher, married Moore’s widowed mother, Marie-Eugènie Rondet Malherbe, entwining the two “daughters” in a familial relationship that undoubtedly facilitated their artistic collaborations and provided a degree of social cover for their intimacy. An emblem designed by Cahun makes the division of emotional and artistic labor within this partnership clear [fig.4, uncatalogued, 2003 acquisition].

Cahun and Moore rehearsed and photographically recorded the private performances that they staged in their “bedroom carnival” throughout the 1910s, creating something like a new iconography of gendered subjectivity in the process. A photograph of Cahun pouring over an 1899 tome whose lettered spine bears the title L’Image de la femme serves as the point of departure [fig.5, JHT/1995/39/t].

Cahun’s head inclines as she studies this two-volume compendium with its engraved illustrations–cameo portraits of exemplary ladies throughout the ages from Penelope to the Empress Eugènie [fig.6., title page, L’Image de la femme by Armand Dayot].

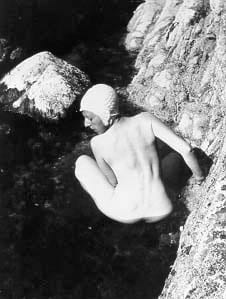

At Cahun’s elbow, a box camera–emblem of representational agency (and perhaps a figure for the eye of Moore within this photograph)–counteracts the mind numbing effect of the feminine stereotypes that permeated the visual and literary culture of their era. With the help of a simple box camera, Cahun and Moore would scrutinize such clichés, image by image, and formulate responses to them. In one example, Cahun (or is it Moore?) turns her back to the camera and to a pool of still water that captures her reflection, as if to reject (twice over) the stereotypes of narcissism linked with feminine subjectivity as well as homosexuality [fig.7, JHT/1995/29/n].

During these years, Cahun penned new scripts for misunderstood heroines (Sappho, Cinderella, Salomé, Eve, Judith…) and Moore applied her formal training as graphic artist to the creation of pen and ink illustrations. “Feminism is already in the fairytales,” Cahun remarked, the slightest shift in the angle of view will make the suppressed content plain.5 Cahun reformulated a dozen or so fables from the viewpoint of their “misunderstood” heroines and contributed several, including “Judith, la sadique,” to the prestigious literary journal Mercure de France 6 for publication. She and Moore intended to publish a fully illustrated version of the collection under separate cover, but never realized this ambition. We encounter Moore’s sardonic humor in the face of the castrating Judith that she created to illustrate this project, a face that bears more than a passing resemblance to that of her partner [fig.8, 2003 acquisition, uncatalogued].

The typescripts and illustrations that survive in the Jersey Heritage Trust collection enable us to imagine how such a publication might have turned out. Yet the circumstances that prevented Cahun and Moore from bringing the project to fruition remain a mystery.

The couple had already succeeded, after all, in publishing one illustrated book, Vues et visions, in print in 1919. As the title implies, the volume juxtaposed paired vignettes transforming contemporary “views” (two weathered skiffs tethered to an abandoned pier in the Brittany seaport of Le Croisic) into poetic “visions” (the stone figures of two boys permanently united in loving proximity upon a tomb in ancient Greece).7 An illumination by Moore frames each page of text penned by Cahun [figs.9-10, pgs 74 & 75 of Vues et visions].

Each set of illustrations forms a sort of theatrical proscenium converting a double-page spread into a theatrical space within which the commonplace stuff of everyday life can reveal, through poetic transformation, new levels of meaning. More specifically, the images conjured up for us reverberate with homoerotic double sense, participating in a homophile reconstruction of antiquity underway since the late nineteenth century. Indeed, this album’s publication could be viewed as Cahun and Moore’s artistic coming out, since it undoubtedly raised their public profile as an artistic couple, and affirmed (albeit in code) their affection for each other and the legitimacy of their bond.

A year after the publication of Vues et visions, Cahun and Moore migrated from the provinces to Paris and opened the doors of their left-bank atelier to a dynamic population of intellectuals, artists, and political activists [fig.11, JHT/1995/15/a].

of the theatrical establishment (Edward de Max and Marguerite Moreno of the Comédie Française) as well as their engagement with experimental theater (in association with Pierre Albert-Birot, Paul Castan, Georgette Leblanc, Georges and Ludmilla Pitoëff, Beatrice “Nadja” Wanger, and Berthe D’Yd).

From 1925 to 1927, Cahun and Moore adhered to Les Amis des Arts Esotériques and participated in the life of the Théâtre Esotérique, founded by Berthe D’Yd and Paul Castan. The troupe specialized in what one reviewer described as “dramatic tableaux that made one dream, because of the preciousness and refinement of the palette, of Oscar Wilde’s Salomé.”8 Cahun assisted with, and occasionally performed in, the theater’s esoteric spectacles–which included Sâr Péladan’s Babylone, La Prométhéide, and Oedipe et le Sphinx. These productions were staged in a cultural center founded by the Société Théosophique. Moore, by then an accomplished designer, offered her services to the company. The theatrical and fashion designs preserved in the Jersey Heritage Trust archives leave little doubt as to Moore’s professional promise in this realm. Her schematic costume drawings, like the ones she conceived for stage idol Edward de Max, are sure-handed and expressive [fig.12, JHT/1995 uncatalogued].

Moore’s fashion plates, though, best demonstrate the originality of her designs. A fashion plate dated 1917, for instance, anticipates the mode garçonne that would sweep post- World-War-I Paris and foreshadows, at the same time, the aesthetic trends that would revolutionize the arts of fashion and fashion illustration in the 1920s [fig.13, JHT/2003/l/16].

Here, a flat-chested girl with a cap of chestnut hair slouches into a stance of studied nonchalance, hands thrust deep into the pockets of her bell-bottom pants. Sporting a bandmaster’s jacket with piping on the cuffs and collar, the model shifts her weight from hind foot to front, calling attention to the coordinated slippers. As if the fashions pictured here–including the woman’s boyish body type and body language–were not sufficiently striking, Moore tosses off a final flourish–the curious treatment of the model’s shadow. The shadowy double, which overlaps its originator like an uncanny apparition, has both an illogical relation to the light source and to subject’s body. What is more, as it crosses the subject and her path to project itself against the wall, it lapses into opacity, effacing the baseboard in the background. The ghostly shadow intensifies the dramatic impact of what might have otherwise seemed a pleasantly decorative, if somewhat sassy, fashion drawing. This and other of Moore’s works on paper from the same period defy easy categorization by drawing upon conventions of stage design and applying them to fashion and the reverse. Another remarkable example pictures a woman blanketed in a mottled cape striding theatrically across the page as if it were a stage [fig.14, JHT/2003/l/20].

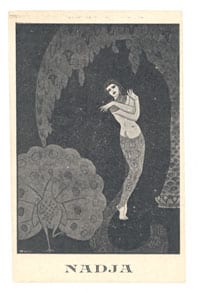

Costume and set designs by Moore for the Théâtre Esotérique have never come to light–however, her photographs of rehearsals and graphics for handbills, posters, programs, and other promotional material attest to her involvement. Much of this material, which captures the symbolist spirit of the theater’s productions, vaunts the charms of an exotic dancer named Beatrice Wanger, or Nadja as she was known [fig.15, JHT/1995 uncatalogued].

Only one or two photographs of Nadja (off stage) survived among the couple’s effects, but a few of Moore’s photos from this period picture Cahun posing as Buddha in the theater’s Theosophist Society locale [fig.16, JHT/1995/35/l].

The experience with the Théâtre Esotérique seems to have edged the couple toward a more serious career commitment to theater. Subsequently, Cahun auditioned before Georges and Ludmilla Pitoëff, whose work was respected within vanguard theatrical circles across Europe. Cahun had second thoughts, though, and declined an invitation to join the company, fearing that fragile physical and mental health would prevent her from keeping pace with occupational demands [fig.17, Moore, portrait of Georges et Ludmilla Pitoëff, courtesy of private collectors, Paris].

She remained in the Pitoëffs’ orbit, however, and closely followed their theatrical ventures.

Indeed, she and Moore seem to have attended the full spectrum of divertissements available in Paris of the 1920s: poetry readings at Adrienne Monnier’s bookstore, academic conferences at the Sorbonne, psychiatric teaching demonstrations at St. Anne’s Hospital, performances of the Russian Ballet at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées, Hollywood movies and jazz-band jam sessions. (Cahun occasionally reviewed such events for the literary journal, La Gerbe, published by her father.) Their conversancy with all echelons of Parisian performance and visual culture enriched the performances that Cahun and Moore continued to stage and photograph at home in their Montparnasse atelier/apartment.

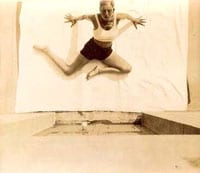

The level of their sophistication with respect to performance reveals itself in a series of aerial shots taken from an upstairs window of their building. Within Moore’s bird’s eye view, Cahun acts out something akin to semaphore code in the courtyard below. A black and white swimsuit abstracts the contours of her prone body and defines her form against the white sheet that serves as a backdrop [figs.18-19, JHT/1995/30/e and JHT/1995/30/c].

In 1926, around the time that these photographs were taken, the expressive dance movement leader Rudolf von Laban devised a “revolutionary alphabet” for the transcription of his choreography. Laban’s code–which synthesized verbal, visual, and corporeal signs–inspired a publication featuring photographs of one of his students, the Czech dancer Milada Mayerová, whose signaling body mediated “a meeting of [the] autonomous arts [for] solving a common task.”10 Somewhat surprisingly, Mayerová’s Alphabet received international critical attention. As Laban, Mayerová, and much of the European artistic avant-guard acknowledged, the alphabet–building block of language (and therefore culture)–offered a logical starting point for the project of cultural reconstruction in the wake of the Great War. Mayerová’s choreographic alphabet may also have held interest as a sort of primer for devotees of expressive dance (a movement that had emancipatory implications with respect to the female body and female sexuality). Moore’s photographs offer evidence that she and Cahun were not only aware of this didactic performance trend but, further, aimed to personalize its rhetoric. Looking at the signals formed by Cahun’s body in this light, it is possible to see the initials “C.C.,” posed back to back in one exposure and an “M” emerging from the side of an “S” in another.

At the other end of the performance spectrum, photographs from this decade picturing Cahun “in training” contain multiple references to more popular pastimes such as boxing and matinee theater. Costumed in boxer shorts, wrist guards, and a leotard inscribed with hearts and the admonition “Don’t Kiss Me I’m In Training,” Cahun balances weights bearing the names of the comic heroes Totor and Popol in her lap, and preens for the camera in a manner that accentuates signs of hyper-femininity: paste-on nipples, painted-on lips, lacquered-down spit curls [fig.20, JHT/1995/30/j].

“Training for what?” she prompts us to ask. Training to become a woman…or to un-become one? Training to be a lesbian? Keeping in mind that theories emphasizing the role of social conditioning in the production of gender (the psychiatrist Joan Riviere’s 1929 essay, “Womanliness as a Masquerade,” for instance), were coming into circulation at this time, we may justifiably consider the couple’s escalating investment in the spectacular arena as a logical extension of their original engagement with L’Image de la femme.

Toward the end of this spectacular decade, Cahun and Moore joined an obscure theater company, Le Plateau, directed by Pierre Albert-Birot, whom they had probably encountered at the Théâtre Esotérique. Albert-Birot–a typographer, poet, and visionary–had long dreamed of venturing into the dramatic arts and Cahun and Moore numbered among the handful of collaborators that he recruited from Paris’ theatrical margins. Cahun performed as Satan (Le Diable) in an adaptation of a twelfth-century mystery play about Adam and Eve, Les Mystères d’Adam, produced by Albert-Birot in March of 1929 [fig.21, JHT/1995/31/u].

She earned critical praise for her role as Blue Beard’s wife (Elle) in a feminist parable, Barbe bleue [fig.22, JHT/1995/30/k],

and also performed as the character Monsieur in a satire titled Banlieu (which was not as well received) [fig.23, JHT/1995/30/h].

Moore apparently did not produce costumes or sets for Le Plateau, but documented several of the plays photographically, including those in which Cahun performed.

Albert-Birot mapped out his research program for new modes of dramatic and poetic expression in a “Programme-Revue” also named Le Plateau. Cahun contributed excerpts of her writings to the publication, where Moore’s portraits of the members of the company were also reproduced [fig.24, Moore, illustrations from Le Plateau].

Le Plateau (the name evokes the “naked stage,” theater at its essence), survived for only one season but left a mark, nonetheless, upon the history of modern theater. Although the members of the troupe invariably outnumbered the members of the audience (they performed Barbe bleue before a single spectator), the productions nevertheless lent impetus to the era’s radical dramatic trends, in dialogue with theorists like Bertolt Brecht (the alienation effect) and E.G. Craig (the displacement of dramatic emphasis from the actor to the scene). Le Plateau was to be a place where “the theater was as purely theater as possible, that is to say a scene that depends uniquely upon the two originators of drama: the Author and the Actor.”11 Reviewers commented on the starkness of the productions, where “no nuance of lighting…no artifice of decor…creates an atmosphere of mystery, of anxiety, of fright à la Maeterlinck.”12 An admirer of Chinese and Japanese dramatic arts, Albert-Birot instructed his actors to paint their faces into characterless masks and trained them to strip their lines to the essence, so that the words became “white”, and the phrasing “monotonous.”13 The dramatic gesture followed suit, reduced of all embellishment, firm, legible, rigorous. “In everyday life, we waste words and gestures because we have time to lose and no one is looking, but the actor, a thousand eyes follow his movements and he has only an hour or two to transmit the drama that he performs, it is therefore indispensable that he act and speak with the greatest economy, on stage no waste, nothing must be lost.”14 Cahun’s body language as she poses for photographs in her Barbe bleue costume conveys something of the choreographic precision that Albert-Birot exacted from his cast members. A note to the metteur-en-scène penned by Cahun “correcting” his staging of her role as Elle evidences the give-and-take that prevailed, however, even in the face of the Albert-Birot’s strong artistic convictions.

Among the convictions that Cahun and Moore shared with Albert-Birot, I would cite a profound mistrust of realist representational traditions, whether they be literary, dramatic, or pictorial. “We challenge realism because the realism we are given is false,” Albert-Birot declared, “…we do not believe that it is real. Today, most actors reproduce reality from the outside, whereas to reconstitute reality from the inside is to create; it is the beginning of creation.”15 With Apollinaire, Albert-Birot envisioned a theater in the round where the audience, activated as participants, occupied the center of the dramatic arena.16 This, too, struck a chord with Cahun and Moore, whose work explored the negotiation of meaning in similarly multilateral terms.

It is easy to understand why Albert-Birot’s ideas about theatrical play (performance as a “mode of research” into new forms of social and artistic interaction) would have inspired Cahun and Moore. Even after Le Plateau disbanded, they remained close to its leader. What is more, their encounters with Le Plateau and Le Théâtre Esotérique emboldened Cahun and Moore to widen their circle of artistic collaborators and to forge alliances with activists in the surrealist milieu. These milieux constituted the artistic and intellectual context in which Cahun and Moore created their second major collaborative publication, Aveux non avenus (disavowed confessions).17 The book, an anti-realist literary mosaic assembled by Cahun, features photocollage illustrations that Moore composed from the store of pictures she had taken of her lover, including several from Théâtre du Plateau performances. Amidst images of Cahun’s avatars and cultural icons (including Oscar Wilde and Alfred Douglas), Blue Beard’s Wife, Elle, attracts our attention at the center of the scrambled family album that introduced the book’s first chapter, for instance [fig.25, moore, heliographic reproduction of collage, plate for chapter 1, Aveux non avenus].18

The emphasis on the stage career within the literary/pictorial framework of Aveux non avenus signals the relevance of theater as a model for the couple’s other artistic initiatives. It is not surprising that Albert-Birot–who strove to free expression from the falsities of a commodity-driven cultural system–chose to publish excerpts from Aveux non avenus in his short-lived review Le Plateau. The book, like Albert-Birot’s endeavors, targets narrativity, realism, the cult of celebrity, and the cult of self.

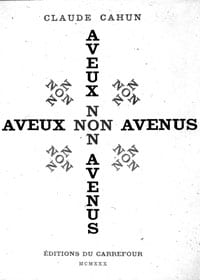

The title Aveux non avenus does not lend itself to facile translation. While “Aveux” may be clearly understood as either “avowals” or “confessions,” the addition of the phrase “non avenus,” which indicates that which has “not happened,” renders the formulation opaque. Most English-speaking scholars choose to translate “non avenus” loosely as “disavowed,” which contains both “avow” and its negation. This play on words captures the spirit of the title, which references, with the word “confessions,” an entire autobiographical tradition while canceling it out in the next breath. The book’s cover graphic prepares us visually for the project’s critical thrust, creating out of the self-contradicting title a canceling “X”–with the palindrome “NON” reiterated at its crux [fig.26, cover Aveux non avenus].

Golda Goldman, the Paris correspondent for the Chicago Tribune who interviewed Cahun and Moore in the 1920s, translated the book’s title more simply: “Denials.”20 Certainly “denials” (as in “no, not interested”) sums up the way most reputable Paris publishers responded at this time to requests to consider the publication of “women’s writing,” with its putatively confessional character. But, even more pointedly, “denial” offered a backhanded way of affirming the literary and personal choices that had marginalized Cahun with respect to Paris’s vanguard literary society–where she nevertheless sought sympathy.

“There are times,” she confessed to Adrienne Monnier, “when I suffer so much from this isolation, of which my nature and all kinds of other circumstances are the cause, that…,” her words trailed off.21 Monnier, in whom Cahun had hoped to find an ally, pressed the aspiring author to try her hand at the journal intime. Cahun’s response?

You have told me to write a confession because you know only too well that this is currently the only literary task that might seem to me first and foremost realizable, where I feel at ease, permit myself a direct link, contact with the real world, with the facts.22

“Don’t get your hopes up,” Cahun added in closing.23 The format that Monnier had recommended must have seemed impossibly burdened with both gendered connotations and testimonial truth-claims. Two years later, in 1928, she presented Monnier with the manuscript of Aveux non avenus, an anti-realist (indeed, surrealistic) critique of autobiography. Would Monnier consider publishing the book? Or would she write the preface? Both requests met with firm and painstakingly explicated denials. “What ever I may do, never could I avoid your objections, too profound, which address the very essence of my temperament,” Cahun ultimately conceded to the woman whose recognition she had sought.24 Monnier’s rebuff, however anticipated, must nevertheless have stung. Cahun and Moore had, after all, championed Monnier’s enterprise, La Maison des Amis des Livres, from its earliest days, borrowing books from the lending library, making purchases, supporting publications, attending the events that transformed the bookstore into an ad hoc cultural center. Cahun paid homage to the spectrum of Monnier’s activities in a piece she published in La Gerbe in 1919.25 She was among the first volunteers to staff the English bookshop that Monnier’s lover Sylvia Beach opened across the street [fig.27, Sylvia Beach portrait, mount inscribed by Beach reads “photograph by Lucie Schwob and Suzanne Malherbe.” (Princeton Libraries, MSS Sylvia Beach Papers, CO 108, Bx 241, F, Photos)].

The title Aveux non avenus does not lend itself to facile translation. While “Aveux” may be clearly understood as either “avowals” or “confessions,” the addition of the phrase “non avenus,” which indicates that which has “not happened,” renders the formulation opaque. Most English-speaking scholars choose to translate “non avenus” loosely as “disavowed,” which contains both “avow” and its negation. This play on words captures the spirit of the title, which references, with the word “confessions,” an entire autobiographical tradition while canceling it out in the next breath. The book’s cover graphic prepares us visually for the project’s critical thrust, creating out of the self-contradicting title a canceling “X”–with the palindrome “NON” reiterated at its crux [fig.26, cover Aveux non avenus]. 19

Golda Goldman, the Paris correspondent for the Chicago Tribune who interviewed Cahun and Moore in the 1920s, translated the book’s title more simply: “Denials.”20 Certainly “denials” (as in “no, not interested”) sums up the way most reputable Paris publishers responded at this time to requests to consider the publication of “women’s writing,” with its putatively confessional character. But, even more pointedly, “denial” offered a backhanded way of affirming the literary and personal choices that had marginalized Cahun with respect to Paris’s vanguard literary society–where she nevertheless sought sympathy.

“There are times,” she confessed to Adrienne Monnier, “when I suffer so much from this isolation, of which my nature and all kinds of other circumstances are the cause, that…,” her words trailed off.21 Monnier, in whom Cahun had hoped to find an ally, pressed the aspiring author to try her hand at the journal intime. Cahun’s response?

You have told me to write a confession because you know only too well that this is currently the only literary task that might seem to me first and foremost realizable, where I feel at ease, permit myself a direct link, contact with the real world, with the facts.22

“Don’t get your hopes up,” Cahun added in closing.23 The format that Monnier had recommended must have seemed impossibly burdened with both gendered connotations and testimonial truth-claims. Two years later, in 1928, she presented Monnier with the manuscript of Aveux non avenus, an anti-realist (indeed, surrealistic) critique of autobiography. Would Monnier consider publishing the book? Or would she write the preface? Both requests met with firm and painstakingly explicated denials. “What ever I may do, never could I avoid your objections, too profound, which address the very essence of my temperament,” Cahun ultimately conceded to the woman whose recognition she had sought.24 Monnier’s rebuff, however anticipated, must nevertheless have stung. Cahun and Moore had, after all, championed Monnier’s enterprise, La Maison des Amis des Livres, from its earliest days, borrowing books from the lending library, making purchases, supporting publications, attending the events that transformed the bookstore into an ad hoc cultural center. Cahun paid homage to the spectrum of Monnier’s activities in a piece she published in La Gerbe in 1919.25 She was among the first volunteers to staff the English bookshop that Monnier’s lover Sylvia Beach opened across the street [fig.27, Sylvia Beach portrait, mount inscribed by Beach reads “photograph by Lucie Schwob and Suzanne Malherbe.” (Princeton Libraries, MSS Sylvia Beach Papers, CO 108, Bx 241, F, Photos)].

She knew Monnier well, knew her as an unbending taskmaster, an exacting critic, a trail-blazer. She knew Monnier’s taste in literature, was aware of her aversion to surrealism (a movement with which Cahun identified). “Denial,” then, not only describes Cahun’s response to Monnier’s editorial suggestions, and Monnier’s (inevitable) rejection of Cahun and her book, it also describes Cahun’s psychic disposition with respect to the impossibility of Monnier’s complicity, which she had nevertheless obstinately courted. It was not in Monnier’s literary world, however, that Cahun and Moore would find their community of peers, but in the arena of politics.

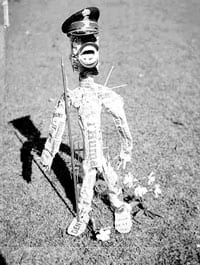

In 1932, Cahun joined the Association des Ecrivains et Artistes Révolutionnaires, where she encountered the surrealist leader André Breton. She (and more rarely Moore) signed, and helped to compose, many of the political tracts generated by Breton and his supporters during the 1930s. In 1934, Cahun published Les Paris sont ouverts (bets are on) a brilliant defense of poetry’s political potential, which earned her Breton’s grudging respect (despite his homophobia). Cahun participated regularly in surrealist demonstrations, strategy meetings, publications, and exhibitions during this period, while Moore remained active behind the scenes. The puppets and surrealist objects that Cahun (and Moore?) produced and photographed during the 1930s negotiated between the theater of political opposition and the theatre of dreams, the psyche and the revolution, the two poles, in other words, of surrealist practice.

As the surrealist group–and, moreover, the political left in France more generally–divided into antagonistic factions, Cahun sided with Breton. The acts of puppet theater that she staged and photographed at this time dramatize positions consistent with those that she advanced in collective publications such as Dissolution de Contre-Attaque (1936). In one mise-en-scène, for instance, a tiny German officer whose body Cahun had crafted out of the communist newspaper L’Humanité signals the merger of two totalitarian schools of thought, that of Hitler and that of Stalin [fig.28, Poupée I, JHT/1995/42/i].

In retrospect, it is tempting to view these “puppets” as harbingers of the creative acts that Cahun and Moore would stage on the Isle of Jersey during the German Occupation. However, in 1936, the idea of moving to Jersey–not to mention trepidations about the occupation of Paris–may not yet have broken the horizon of their conscious minds.

A year later, though, Cahun and Moore packed up their affairs and moved to St. Brelades, a remote parish on the isolated Channel Island of Jersey. One can only speculate as to their motives. Disillusionment with the political climate in Paris (the outbreaks of anti-Semitism, the violent schisms that divided the left and broke up their circle of friends) undoubtedly influenced the decision to seek a more harmonious environment. But why the Isle of Jersey? They had vacationed on the island and knew that it would offer them a haven where they could consider their options in relative serenity. But this was also true of Le Croisic, in Brittany, which had the advantage of being more convenient to Paris. The Channel Islands, on the other hand, were a world apart, a world in between–not part of the United Kingdom, closer to the Normandy coast, an historic place of piracy and literary exile. Was it the neutrality, the history of sanctuary, the cultural hybridity and political inconsequence that attracted the couple? They had discussed expatriating to Canada–but Jersey, at least, lay close enough to France’s shores to permit the maintenance of bonds of affinity and affection. (Henri Michaux, Nadja, Henri Barbier, Breton and Jacqueline Lamba visited them on the island, for instance.)

Not long after Paris was invaded by German military forces in 1940, Jersey suffered the same fate. Cahun and Moore decided to stand their ground, rather than fleeing to England as fully half of the islanders had. In fact, they launched a two-woman anti-nazi propaganda operation, blanketing every part of the island with handmade tracts. Cahun’s war memoir describes how she and Moore succeeded in creating the illusion of a large-scale resistance movement. After several years at risk, they were arrested for high crimes of treason and were subjected to arduous interrogation because they refused to reveal the names of their male collaborators. The investigating officers found it impossible to believe that two middle-aged women had conducted such a daring campaign “all alone.” “They were forced, at the end of the day, to condemn us without believing in our existence,” Cahun concluded.26 This tour-de-force performance, under fire, represents the end-logic of the couple’s career of theatrics: from the photo play of two defiant lovers, to collective acts of cultural subversion, to the (fragile) dream of political community, to acting as one (acting as if they were many) in resistance to military domination.

When I look at Moore’s pictures of Cahun [figs.29-30, JHT/1995/31/l, JHT/1995/31/k, JHT/1995/16/v, and JHT/1995/31/m]

taken just after the liberation, when the two returned to their home to dance along the fortifications that the German’s had built in their garden, a phrase from Aveux non avenus springs to mind: “Victorious! Sometimes victorious over the most atrocious inhibitions, a last-minute maneuver corrects a shadow, an imprudent gesture–and beauty is reborn.”27 I think, too, of the enigmatic pictures that Moore later took of another wall, at the end of a smaller garden, looking out over the same sea from the modest house that she purchased for herself after Cahun’s death. There I see a naked stage, haunted by the absent subject of Moore’s photographs, life-long object of her devotion and desire [fig. 33, the empty garden wall viewed from Moore’s backyard, JHT, print from uncatalogued negatives].

1. Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida, 31-32.

2. The “self-portraits” attributed to Cahun have figured prominently in several major exhibitions (for instance, Inverted Odysseys: Claude Cahun, Maya Deren, Cindy Sherman at NYU’s Grey Gallery) where this work was–not for the first time–compared to that of Cindy Sherman. This exhibition is not the first to compare Cahun’s photographic project to that of Cindy Sherman. From the moment of Cahun’s “rediscovery” in the mid-1980s, Sherman’s oeuvre has consistently provided a point of reference. In a 1986 review, Hal Foster describes Cahun as “a Cindy Sherman avant la lettre” (“Amour faux,” Art in America, January 1986, p.127). Cahun’s biographer, François Leperlier, makes the same comparison in Claude Cahun: l’écart et la métamophose (Paris: Jean-Michel Place, 1992). Katy Kline’s essay, “In or Out of the Picture, Claude Cahun and Cindy Sherman,” follows this pattern (Whitney Chadwick, ed. Mirror Images: Women Surrealism, and Self-Representation, Cambridge: MIT Press, 1998). Although Cahun is often cast as Sherman’s precursor “in the continually reedited film of art’s history,” Shelly Rice points out that “anyone who has seen one of Cahun’s tiny, black-and-white prints next to gargantuan, garish color photographs by Sherman knows that there’s more to this comparison than meets the eye” (Inverted Odysseys, p.24).

3. Among the many art historians who have explored the art of portraiture from this perspective, I would site Svetlana Alpers path-breaking and still engaging work on Rembrandt’s theatricality in Rembrandt’s Enterprise: The Studio and the Market (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988).

4. François Leperlier, “L’Exotisme intérieur,” Claude Cahun, Photographe (Paris: Jean Michel Place, 1995), 10. François Leperlier, “Claude Cahun, La gravité des apparences,” Le Rêve d’une ville: Nantes et le surréalisme, eds. Henry-Claude Cousseau et al. (Nantes: Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nantes, 1995), 263.

5. Claude Cahun, Aveux non avenus (Paris: Editions du Carrefour, 1930), 52.

6. “Eve, la trop crédule,” “Dalila, femme entre les femmes,” “Judith, la sadique,” “Hélène, la rebelle,” “Sapho, l’incomprise,” “Marguerite, soeur incestueuse,” and “Salomé, la sceptique” (dedicated to Wilde) appeared in Mercure de France (February 1925):622-643. Le Journal littéraire, 45 (28 February 1925) contained two more pieces, titled “Sophie, la symboliste” and “La Belle.” The manuscript of “L’Allumeuse,” “Marie,” “Cenrillon,” “L’Epouse essentielle,” “Salmacis,” and “Celui qui n’est pas un héros,” which were never published during Cahun’s lifetime, are preserved in the Jersey Historical Trust collection.

7. Claude Cahun, Vues et visions, dessins de Marcel Moore (Paris: Editions Georges Crès & Cie, 1919), 74-75.

8. Unreferenced clipping, dated 29 December 1923, Bibliothéque de l’Arsenal, Paris, RT 3993 SR97/1984,1923.

9. La Salle Adyar, 4, square Rapp, Paris.

10. Vitezslav Nezval, Alphabet, cited by Matthew S. Witkovsk, “Staging language: Milca Mayerova and the Czech Book Alphabet,” The Art Bulletin 86:1 (March 2004), 114. This essay offers a detailed history of the book’s production and convincing analysis of its implications.

11. Pierre Albert-Birot, typescript, Fonds Albert-Birot, Paris.

12. Louis Périé, Le Courrier du centre, Limoges (25 March 1929), unpaginated clipping, Fond Albert-Birot, Paris.

13. Interview, Arlette Albert-Birot, December, 2002.

14. Albert-Birot, “Arts dramatiques,” Le Plateau, no.1. (March 1929), 7.

15. Pierre Albert-Birot, “Arts dramatiques,” Le Plateau, no.1. (March 1929), 12.

16. Albert-Birot also shared with Apollinaire and other members of the Parisian avant-garde an interest in puppet theater as a locus of cultural renewal. He maintained connections with both experimental and traditional puppeteers via two associations–Les Amis de la Marionnette and l’Association nos Marionettes–whose members included Apollinaire, Philippe Soupault, Ivan Goll, Joseph Delteil, Jean Lurçat, Juan Gris, Marc Chagall, and Maeterlinck. Although his own ambitions for exploiting body-puppetry outstripped his technical capabilities and means (he renounced this line of investigation when his body puppets disintegrated in the first minutes of their stage debut), he urged his cast members to subordinate their egos, acting as human marionnettes in the service of a collectively rendered drama text.

17. Claude Cahun, with illustrations by Moore, Aveux non avenus (Paris: Editions du Carrefour, 1930).

18. The Fonds Albert-Birot contains heliographs of the plates that figure Cahun in her theatrical roles as well as a signed copy of Aveux non avenus. Cahun’s effusive inscription begins, “To Pierre Albert-Birot, whom I admire and whom I love, to the poet whom I had the honor of serving as a charmed if not skillful interpreter, happy to have been one of his creatures.”

19. It would not stretch the imagination to suppose that Cahun and Moore consulted Albert-Birot, a skilled and highly creative typographer, about the layout for this cover.

20. Golda M. Goldman, “Who’s Who Abroad: Lucie Schwob,” Chicago Tribune, European Edition, 28 December 1929, 4.

21. Letter from Lucie Schwob to Adrienne Monnier, Paris, 2 July 1926. Institut Mémoires de l’Edition Contemporaine [IMEC], Caen. Mais il est des jours où je souffre tant de cet isolement, dont ma nature surtout mais aussi toute sorte de circonstances sont cause, que….

22. Letter from Lucie Schwob to Adrienne Monnier, Paris, 23 July 1926. Fonds Adreinne Monnier, Bibliothèque Littéraire Jacques Doucet [BLDJ], Paris, MS 8718 B’ I 11. Vous m’avez dit d’écrire une confession parce que vous savez bien que c’est actuellement la seule tâche littéraire qui puisse m’apparaître tout d’abord réalisable, où je me sente à l’aise, me permettant une prise directe, un contact avec la vie concrète, avec les faits….Mais je crois avoir bien compris de quelle façon, sous quelle forme vous entendiez cette confession (en somme : sans tricherie d’aucune sorte).

23. Letter from Lucie Schwob to Adrienne Monnier, Nantes, 23 July 1926. Fonds Adreinne Monnier, BLDJ, Paris, MS 8718 B’ I 11. N’ayez pas grand espoir.

24. Letter from Lucie Schwob to Adrienne Monnier, Nantes, 2 July 1926. Fonds Adreinne Monnier, IMEC, Caen. D’ailleurs, quoi que je fasse, jamais je ne pourrai éviter vos objections, trop profondes, qui s’adressent à l’essence même de mon tempérament.

25. Claude Cahun, “Aux Amis des livres,” La Gerbe (February 1919).

26. Cahun, “Le Muet dans la mêlée,” 1948, published in Leperlier, Ecrits, 627, 629-30. La Gestapo chercha quatre ans en vain. Si nous avions pu vivre parées contre toute perquisition, si soudaine fut-elle, ils n’auraient jamais cru, malgré leurs informateurs, qu’il s’agissait de nous. Même toutes preuves en mains ils n’en croyaient pas leurs yeux. Ils restaient persuadés que nous ne pouvions être plus que des comparses, complices de …X. Pour obtenir qu’ils cessent de nous interroger au sujet de nos affiliations hypothéthiques avec…x, ou avec l’Intelligence Service (!!!), il nous fallut leur démontrer que nous etions pleinement conscientes et capables de nos “crimes.” Un peu de patience–de part et d’autre–y suffit…. Constatant que nous étions des femmes, ces êtres inférieurs…; que nous avions à Jersey la réputation de bourgeoises paisibles, qu’il était impossible de nous faire passer…pour des “terroristes”; que, lors de notre arrestation–devant témoins jersiais–nous n’avions fait aucune résistance; que vis-à-vis d’eux-mêmes, ce soir-là et au cours des interrogatoires, nous n’avions qu’une hostilité froide, exempte de toute violence émotive…ils y perdirent leur “aryien”: notre “idéalisme” passait leur conception cynique de l’espèce humaine. Cela piquait ce qui malgré tout subsistait en eux de curiosité psychologique….À Jersey, ils durent, en fin de compte, nous condamner sans croire à notre existence. En quelque sorte. Comme à regret.

27. Cahun, Aveux non avenus, 57.

Photo ©Grover Sales

Photo ©Grover Sales