A History of Violence

June 7, 2018

Creative Labor presents:

A History of Violence – Opening Reception

Curated by Rudy Lemcke

SOMArts Cultural Center, 6-9pm

The Q-Ball – #Resist Performances: 7:30-8:30pm

Exhibition through June 28; Walk-Through: June 16, 11am

Gallery Hours: Tuesday–Friday noon–7:00 p.m.. Saturday noon–5:00 p.m

Free Admission

Our Facebook Page: https://www.facebook.com/events/1466099273536418/

Opening Reception features food, drink, music and the QBall: performances from artists of the 2018 National Queer Arts Festival.

Visual Artists include: Arthur Dong, David Wojnarowicz, Cassils, Jamee Crusan, Jamil Hellu, Bren Ahearn, Jason Hanasik, Kadet Kuhne, Julie Tolentino and Stosh Fila, Jaime Cortez, Xandra Ibarra, Việt Lê, Angela Hennessy, and Tim Roseborough.

The Turning, Queerly

A History of Violence

A History of Violence is a history of becoming.

Violence is defined by the World Health Organization as “the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community, which either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, mal-development, or deprivation.”

It is perpetrated through politics, economics, and culture – and made real through human interaction. Poverty, social injustice, state sponsored brutality, racism, sexism, homophobia, intolerance, and oppression are examples of its instrumentality. All are symptomatic of systemic violence manifesting itself in our daily experience of the world.

The LGBT community was born and shaped by violence like this. Through social and cultural exclusion, criminalization, medical objectification, religious persecution, artistic censorship, familial rejection and historical erasures, our identities were forged—for better or worse.

We exist in a world where these dynamics of power and control are already operating for and against us. Because of this, the psychic and physical effects of violence are a part of who we are.

Is resistance possible?

The idea of resistance itself implies a point outside of the system from which to act and critique this violence. But what if there is no outside? If so, could there instead be a place of turning from within that might trigger the emergence of a new becoming, queerly? What would this turning look like? What would it feel like?

This exhibition explores the work of artists who have gazed deeply into the flame of violence, and reacted in ways that allow us a compelling look into queer existence.

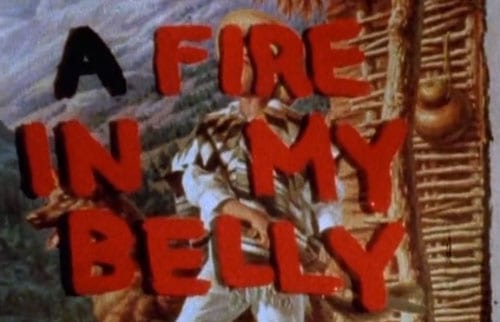

These issues are tackled in the work of artist and activist David Wojnarowicz (1954-1992). His film A Fire in My Belly was part of the acclaimed exhibition curated by Jonathan D. Katz, Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture (2010). Shortly after the opening of the exhibition, the film was censored and removed by political maneuvers of conservative religious leaders and right wing politicians. The film’s removal evoked an immediate response from the LGBT community, epitomizing an all too familiar attack on LGBT rights. Specifically, it represented an attack on our right to self-identity, the right to visibility, and ultimately the right to personhood that the Hide/Seek exhibition celebrated. This attack signaled to queers everywhere a revival in the culture war organized around an oppressive ideology that views homosexuality as a mental disorder at worst, and a sinful “lifestyle choice” at best.

The censorship of Wojnarowicz’s film ignited immediate protests. Spontaneous “emergency screenings” of the film across the country in museums and community spaces started a national conversation about LGBT art and censorship. This invigorated the work of queer artists and activists. The spirit of coalition and mobilization built on the legacy of early AIDS activists was revitalized and empowered by the immediacy and reach of social media.

The film is an unfinished work of raw emotion. It is a keen social critique. Its flashing jump cuts embody the violent crash of cultural ideologies and the burn of abject otherness. It shows at its core an unrelenting, unresolved conflict of cultural and political injustice that is the fire that Wojnarowicz leaves as his legacy in art and activism.

Following David Wojnarowicz, it is powerful, meaningful art with purpose that inspires this assembly of artistic voices as well as the community from which and through which they speak.

The artists in the exhibition are: Arthur Dong, Jason Hanasik, Bren Ahearn, Cassils, Jamee Crusan, Xandra Ibarra, Jaime Cortez, Julie Tolentino / Stosh Fila, Việt Lê, Tim Roseborough, Angela Hennessy, Kadet Kuhne, and David Wojnarowicz.

A History of Violence is the second part of a curatorial trilogy called The Turning, Queerly that includes: From Self to #Selfie (2017), A History of Violence (2018), and Precarious Lives (2019). The project reconsiders the notion of the self as self-with-others; explores the scene of violence and trauma as trigger and turning point; and proposes a rethinking of alliances and old models of political organizing that looks to reform the ideas of self and community.

The miracle that saves the world, the realm of human affairs, from its normal, “natural” ruin is ultimately the fact of natality, in which the faculty of action is ontologically rooted. It is, in other words, the birth of new [people] and the new beginning, the action they are capable of by virtue of being born. Only the full experience of this capacity can bestow upon human affairs faith and hope. ~Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition

How do we engage with the work in this exhibition?

Arthur Dong

We begin by witnessing the testimony of convicted killers of gay men, recorded by filmmaker Arthur Dong in his 1997 documentary, Licensed to Kill.

Here, we find unfortunately familiar narratives, such as: a young man murdering another in “self-defense of sexual advances”–a defense known as “homosexual panic”; a self-loathing, religious gay man who took the lives of innocent homosexuals because of his own repressed tendencies; a victim of child abuse who feared losing his manhood; an army sergeant angry over gays in the military; and a self-described homeboy looking for easy prey. Deeply held narratives like these are the constructs of systemic violence that create an internal shadow image of LGBT people as unworthy of selfhood, and along with that, deserving these acts of erasure.

GLBT History Archive

White Night Riot, courtesy KTVU-TV, digital video.

The GLBT Historical Society and Archive houses countless documented incidents of anti-LGBT violence meant to erase identity. These range from the early days of the LGBT community to current accounts of the increase in anti-trans violence. For some of us, artifacts carefully displayed in a pristine museum case can resonate and glow like cinders—the smoldering residue of injury and hurt. But it is in this archive of memory and feelings embodied by these objects, and in this preservation and re-presentation of our history and cultural legacy, that we can rightly reveal and witness our power. It is within this historical frame, and the turning of oppression back upon itself, that allows us to reclaim it as our history of self-awareness and agency. This is the uneasy center of our history of becoming.

Jason Hanasik

Jason Hanasik’s beautiful photo series I Slowly Watched Him Disappear was completed over the course of four uneasy years. It follows Sharrod, a high school student in Virginia Beach, VA, from his freshman to senior year. During his matriculation, Sharrod chose to become a member of the National Junior Reserve Officers Training Corps (NJROTC).

This series sheds light on a moving transformation of its subject from boyhood to manhood. We find it here to be a complicated intersection of social, political, and cultural forces in which the photographer is both witness and silent actor. These compelling photos reveal two complex masculinities in its study of kinship and rite of passage, Sharrod’s disappearance becoming the slow appearance of the artist.

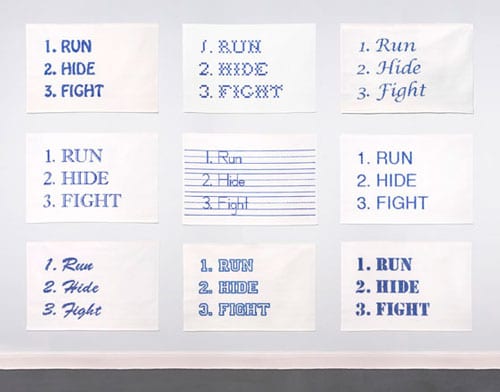

Bren Ahearn

Active Shooter Directions is Ahearn’s series of cross-stitch samplers, each a reference the slow education-by-handwork of young, early American women. In this “training,” the gender of femininity is literally sewn into the fabric of everyday life where it comes to be so embodied that it becomes unconscious muscle memory. As an educator, Ahearn works in institutions that now train students to respond to active shooter situations where gun violence and school shootings have become tragically common. The simplicity of the stitched words “Run,” “Hide,” and “Fight” have come to replace the A, B, C’s as a grim lesson that American youth must now learn.

Cassils

Cassils, 103 Shots

Cassils’ 103 Shots is a response to the mass shooting at Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Florida (1996). In testimony about the incident, one of the survivors recalled that the sounds of gunshots were initially perceived as “fireworks or balloons popping,” and didn’t register as a danger. From this narrative, Cassils created a short film shot on the day of the San Francisco Pride celebration. “Filmed in Dolores Park, the footage presents stark black and white imagery of a series of pairs of couples and friends bursting a balloon between their bodies with the pressure of an embrace. The faces of the film’s participants register affection, surprise, pain, discomfort, and laughter; each embrace is a minor enactment of the disorienting effect of violence in the space of intimacy. 103 embraces, 103 shots, one for each life lost or irreparably altered.” – Cassils

Jamee Crusan

The work of Jamee Crusan also uses the scene of the Pulse nightclub shootings as the trigger for their work. The lush materiality of the felt and the saturated color of cyan, draw us closer to these objects. We want to feel these pieces—to touch the thing-ness of their presence. But the seductiveness of this work belies the hidden violence of its creation. The embedded gunshot/wounds tear at Untitled (Felt), explode/scar in Treasures Buried Deep Are Often Guarded By The Deadliest Of Demons, and leave a permanent reminder cast in bronze of an unresolved melancholy that we feel in You Can’t Cheat Grief.

For several of the artists in the exhibition, the body is the scene of violent acts of erased presence, obsessive desire, and the mocking complicity of power dynamics. Each in their own way is a defiant act of self-possession and reclamation.

Jamil Hellu, 100 Years of Solitude (2014), Digital pigment print.

Jamil Hellu

100 Years of Solitude was created in response to the 2013 Russian anti-LGBT propaganda law and Moscow’s ruling for blocking permissions to organize pride parades for the next 100 years. Hellu’s piece expresses solidarity with artists around the world who are speaking out against human rights abuses and bringing attention to the sociological ramifications of homophobia.

Jamil Hellu, 24 Variations for a Stoning Rock (2016), Animation, 00:24″ loop

The accompanying text for 24 Variations for a Stoning Rock reads: The size of the stone used in stoning shall not be too large to kill a person by one or two throws and at the same time shall not be too small to be called a stone. A chilling reminder of legitimized violence committed in the name of the father.

Jaime Cortez

Devoid of the body—the human subject—the photo work in The Salvage Series adapts images of crime scenes to telling ends. Here, they act as evidence of crashing ideologies, the collision of “American” identities, and the refusal of an othering value system. The sculptures turn in their own radiant accumulation, shimmering in the light of excess.

Is this an archeology of consumer culture? Or are these images and things a queer “turn” on the word salvage—salvage as an affordance, a calling out to the viewer to recover what has been lost and what has collapsed.

Kadet Kuhne

Kadet Kuhne, Null Extension – 2 channel video with 5.1 sound.

In Kadet Kuhne’s Null Extension we are asked to bracket our world and consider an alternative experience manifesting itself within the restraints of perception. Beyond the binaries of language it points to an unknowable site that we are given access to in the form of audio signals that are perhaps the pre-linguistic residual artifacts of this impossible state. We experience the movement of being that is sensed but not known.

Julie Tolentino / Stosh Fila

HONEY (performance documentation) , 2013, Video shot and edited by Nagy Krisztián and Nikolai Kozak. Four-hour outdoor durational performance by Stosh Fila and Julie Tolentino in Abu Dhabi, UAE. Appreciation the generous support of the NYUAD Theater Program & Professor Debra Levine, PhD.

The Cry of Love – Honey installation is the video documentation of a four-hour performance by Julie Tolentino and Stosh Fila. Witness the slow drip on a golden thread of honey from performer (above) into the mouth of performer (below). A complex emotional presence is created and ritualized by the video document of this performance. Is this the enduring pain of an insatiable need, or the pleasure of satisfaction? Are the performers active or passive in their roles as givers and receivers? At what point do we stop watching, walk away and exit the scene? Have we exposed ourselves by watching? Have we been compromised? Are we made vulnerable and complicit in its sweet violence?

The distortions of fragmented, displaced, and colonized identities are amplified in many of the works in this exhibition. The unsettled, uncanny body wanders queerly in from the sidelines.

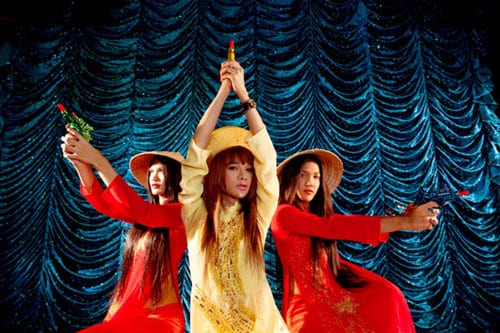

Việt Lê

Việt Lê’s Love Bang Trilogy includes the videos eclipse, heartbreak and lovebang!, each echoing the uncanny voices of the dispossessed. They are a symptom of the deep wound of cultural violence, the ghosts of a haunted history, the heartbreak of love and loss distorted by the past, and the forgetfulness of being—embodied by a homeless foreign boy lip-syncing a pop identity.

Tim Roseborough

Tim Roseborough, Casual Cruelties, 2017, 9 Digital Prints; 10:50 minute Video Loop; and Plastic Buckets and Candies.

Tim Roseborough’s Casual Cruelties is a cycle of nine videos and sculptural elements that explore how long-standing historical conditions can influence casual and intimate human interactions. The work demonstrates how subtle gestures or an off the cuff remark can become unintended weapons. This cycle of videos consist of an “actor” and “subject” who maintain an ambiguous and charged relationship. The interactions allude to histories of domination and colonialism performed in the ordinary and casual encounters of daily life. The seductive candy-coated give-away gifts of the artist seduce and implicate the viewer in this dynamic social exchange.

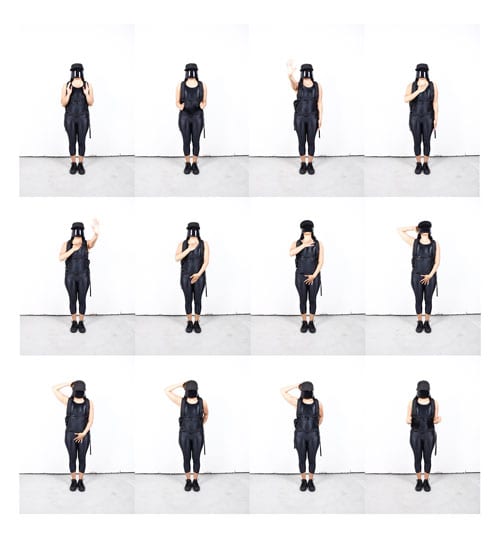

Xandra Ibarra

Xandra Ibarra, Spic Skin (Cucaracha), 2016, archival pigment print on canvas.

In another vein, the large-scale photographic piece by artist Xandra Ibarra is part of a series called Training for Exhaustion (For the Unintelligible). The photo presents a vacuum-sealed costume as an artifact of exhaustion; a by-product; an empty space where the subject is literally vacuumed out. This is the residual artifact of transformation, the violence of becoming, and vacant site for locating Ibarra’s body without an image—an incorporeal gesture of the self.

Xandra Ibarra, Cucaracha Lenses, 2015, plastic visors

Ibarra’s Cucaracha Lenses (Visors) are an ironic twist on the trope of riot gear worn to protect police from protestors. Here, the visors are a different type of riot gear meant to protect the protestors from the policing of identity in an age of surveillance and control. Invisibility is subversively re-inscribed on these objects as the right to opacity and refusal.

Xandra Ibarra (with photographer Autumn Swisher), Taking on the Corporeality of a Cockroach, 2015, Mounted Digital Print

In Ibarra’s public performance Training for Exhaustion (For The Unintelligible) we are asked to consider fatigue as a primary mode of being through which we experience our historical moment. Fatigue occurs when a material (in this case humankind) is subjected to the repeated loading and unloading of stress—the stress of identity. The performance prepares a group of “subjects” for transformation into a radicalized species capable of “intelligence, molting, evasiveness, breeding, durability, mutation and speed” – cockroaches. The work’s poignant humor offers us a radical rethinking of our response to cultural violence. It offers us endurance training, a workout, a heightened sense of corporality and interconnectedness—a turning through which we can prepare our precarious lives for resilience and futurity.

Angela Hennessy

Angela Hennessy, Bling, 2018, synthetic and human hair, artist’s hair, hair rollers and foundations, foam, athletic tape, twist ties, wire, elastics, chenille stems, velcro, enamel paint, gold leaf, copper sheet, glitter, black lava sea salt, pigment, steel knobs, wooden rings

Angela Hennessy’s recent work explores the idea of intertwined narratives and histories that are embodied in the materiality of experience. Her use of hair purchased from a local beauty supply house near Hennessy’s studio in West Oakland locates the material production of the work within a familiar world that reaches out to a shared lineage and heritage of black cultural tradition that co-exists despite aesthetic hierarchies. Into this, Hennessy weaves the practice of the use of hair in Victorian crafts of mourning and grief; of loss and remembrance. This is the work of memory and recovery—the labor of the care of self.

With her piece Bling we are presented with an idea of the ephemeral quality of reflected light and the flash of adornment. The title of the work refers to the shimmering golden necklaces worn by rappers to symbolize wealth and power, success and dominance. But in the quality of the blinding flash lies the trace of embedded histories of colonial power, of conquest and oppression and the chains that once bound people to the horrors of slavery. The trope of the necklace combined with the work’s references to shackles and collars re-inscribes these forms with beauty and libratory power. We bear witness to the reclamation of cultural presence. It embodies the ebb and flow of materiality and the flux of power dynamics. Its meaning is a flash of reflected light, the bling of adornment from the surface of a deep cultural wound.

David Wojnarowicz

We end our history where we began, with the unfinished work of David Wojnarowicz and the fire in our bellies that is the turning queerly toward a future that we claim as our own.

– Rudy Lemcke 2018

Thank you to our funders: