Things Are Queer

Things Are Queer

by Jonathan Weinberg

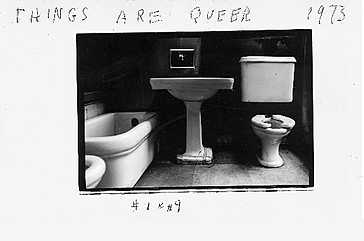

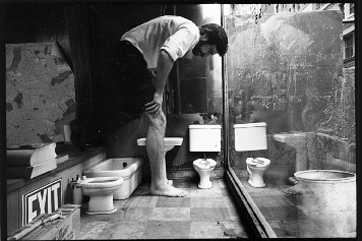

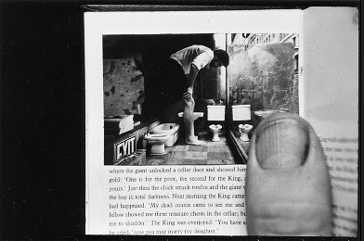

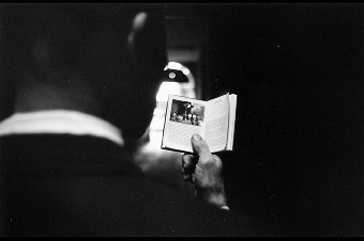

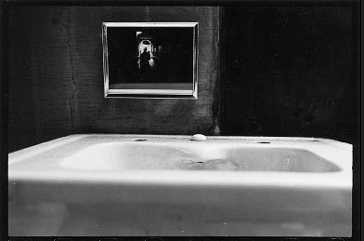

The first photograph of Duane Michals’s series Things Are Queer (fig.1) depicts a simple bourgeois bathroom. Picture 2 introduces a pair of enormous hairy legs. AS the series continues, the camera moves back, revealing that it is not the legs that are unusually big, but the toilet, sink, and bathtub that are small. The camera retreats again and we become aware of an enormous thumb on a page. It turns out that what we have really been seeing is someone looking at a picture in a book of a man standing in a tiny bathroom. AS if in a film, the camera keeps panning back. The man reading the book is in a dark corridor. In the penultimate photograph we find that this walking and looking man is merely a blowup of an image that is in the mirror in the bathroom. With the final image in the series we have come back full circle to the original toilet, sink, and bathtub.

On the face of it, Michals’s subject has nothing to do with homosexuality (though its landscape of bathroom, dark corridor, and voyeurism may have vague sexual connotations). The queer of Things Are Queer is not a matter of specific sexual identities but of the world itself. The world is queer, because it is known only through representations that are fragmentary and in themselves queer. Their meanings are always relative, a matter of relationships and constructions. In contradiction to its title, the series seems to say the things themselves are not queer, rather what is queer is the certainty by which we label things normal and abnormal, decent and obscene, gay and straight.

Michals’s series could stand as an allegory for the current ambitions of lesbian and gay studies to go beyond documenting specific homosexual identities and cultural practices. Increasingly its charge is to investigate the mechanisms by which a society claims to know gender and sexuality. Homophobia is not a mere by product of the ignorance and prejudice of a segment of the population, but an aspect of the way power is organized and deployed throughout society. As lesbian and gay theorists are fond of pointing out, the word heterosexual was only coined after homosexual–both terms are late nineteenth-century inventions. It is as if the dominant culture needs the Other to be certain of itself. Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s Epistemology of the Closet begins with the claim that “the major nodes of thought and knowledge in twentieth-century Western Culture as a whole are structured–by a chronic, now endemic crisis of homo/heterosexual definition.” 1 Queering the text is more than pointing to potentially gay and lesbian characters or insisting on the sexual identity of an author, it involves revealing the signs of what Adrienne rich called “compulsory heterosexuality.” 2

The very terms lesbian and gay may seem tied to an outmoded identity politics. Several of the authors in this Art Journal issue prefer to term queer. (Note: This article is reprinted from Art Journal, Winter, 1996) Queer is more encompassing. It can be taken to refer to a whole range of possible identities–gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender–or even a hind of fluid state between these orientations. As a field of inquiry, queer studies potentially shifts the emphasis away from specific acts and identities to the myriad ways in which gender organizes and disorganizes society. However, there is a danger in this shift. If homophobia is everywhere, and everything and everybody is potentially queer, then the specific stories of how gay and lesbian people have lived and represented their lives, as well as the record of their persecution and struggle for civil rights, may be passed over. Robert Atkin’s essay, “Goodbye Lesbian/Gay History, Hello Queer Sensibility,” ( Art Journal, Winter, 1996) warns that what may be missed in queer theory is the politics and history of lesbian and gay communities. This danger is particularly strong in art history, which among the humanities has been relatively late to raise the issue of the relationship of art and sexual identity in a sustained fashion. Although there has been an increasing number of essays on lesbian and gay themes in art, there are still only a handful of full-length studies of the subject. This lack is even more acute when it comes to lesbian themes. Queering all works of art–that is, making them strange in order to destabilize our confidence in the relationship of representation to identity, authorship, and behavior–is a potentially political act, but it should not replace the task of recovering gay and lesbian iconographies and historical moments. As Christopher Reed insists in the introduction to “Imminent Domain: Queer Space in the Built Environment,” (Art Journal, Winter, 1996) queer and queerness are themselves historically specific terms that have their own social and political context and their won genesis. It is impossible to imagine queer theory existing without the identity politics of the pre- and immediate post-Stonewall era, or the later street actions of ACT UP. Queer theory is deeply indebted to feminist and African-American writings, just as lesbian and gay liberation itself was build on the model of the women’s movement and on the struggle for black civil rights.

In the end, I do not think it is necessary to choose between queer studies or lesbian and gay studies. We should feel free to move between them and even confuse them. Ideally, the two approaches–the queer, more theoretical and improvisational, the lesbian and gay, more dependent on the archive and biography–can go on simultaneously. Both require the sustained effort of the dissertation and the book, and the financial and moral support of the art historical establishment. Despite the Art Journal’s support of this special issue, the discipline of art history (and the academy as a whole) still takes gay and lesbian/queer studies as a minor area of expertise, a queer endeavor.

From its beginnings in the writings of Johann Winckelmann, art history has been a closeted profession in which the erotic is hidden or displaced. James Small’s essay in this issue, (Art Journal, Winter, 1996) making “Making Trouble for Art History: The queer Case of Girodet,” suggests the negative effects such a displacement has had on studies of Girodet’s paintings. Erica Rand, in Teach me Today: finding the Censors in Your Head and in Your Classroom,” explores the way institutional pressures are so pervasive that we often become our own censors, reproducing the oppression of the dominant culture. Still, there is a danger that in castigating art history and the academy for its prudery, we are beating a dead horse. We who do lesbian and gay/queer studies gain not a little satisfaction in believing in the conservatism of art history and the scandal of speaking of sex and deviancy. Michel Foucault begins his History of Sexuality with an attack on academics who think that raising the issue of sex is necessarily transgressive:

If sex is repressed–then the mere fact that one is speaking about it has the appearance of deliberate transgression. A person who holds forth in such language places himself to a certain extent outside the reach of power; he upsets established law; he somehow anticipates the coming freedom–for decades now we have found it difficult to speak about the subject without striking a different pose: we are conscious of defying established power, our tone of voice shows that we know we are being subversive, and we ardently conjure away the present and appeal to the future, whose day will be hastened by the contribution we believe we are making”What sustains our eagerness to speak of sex in terms of repression is doubtless this opportunity to speak out against the powers that be, to utter truths and promise bliss”; to pronounce a discourse that combines the fervor of knowledge, the determination to change the laws, and the longing for the garden of earthly delights. 3

I take Foucault’s shifting from talking about “a person who holds forth” to “we” in this passage to mean that Foucault was aware on some level that he, too, participates in speaking transgression. His unfinished project for a history of sexuality is, in spite of himself, part of a liberation movement that arose out of the very “fervor of knowledge, determination to change the laws, and the longing for the garden of earthly delights” that Foucault mocks. Still, Foucault is correct to suggest that merely speaking of sex is not the same as transgression–often such speech may be the means to traditional academic success. On a deeper lever, he seems to be questioning a central premise of lesbian and gay liberation, that speaking frankly of sexuality, particularly one’s own sexuality, is a means toward freedom. But certainly the risks and rewards involved in adopting a confessional mode are not merely a matter of content, but also of context, of who is speaking and to whom. Although many of us have become suspicious of the simplistic binarism inherent in the very concept of the closet (in/out, straight/gay, heterosexual/homosexual), for others the act of coming out is still enabling, precisely because its terms are so simple, and the imperative seemingly so clear. But here is another story, as Juba Clayton’s performance “Closet Ain’t Nothin’ but a Dark and Private Place for?” suggests. Because of the enormous pressure of race, class and gender prejudice, coming out may be too great a risk for many women of color. HIV/AIDS has also shifted the terms of the closet. Coming out as having the HIV virus may bring on new and more frightening oppression. It is this oppression that makes Ann Meredith’s artist project, in which she helped women with HIV/AIDS make photographic self-portraits, so remarkable. The transgressive, like the closet itself, is not a universal state, but a matter of multiple positions. There are as many kinds of closets as there are lesbian and gay lives.

One of the most obvious differences in terms of positions of power in the academy and in society concerns gender. This issue of Art Journal addresses the presence of lesbian women and gay men in visual culture, but that presence is not equivalent. The complex question of differences and shared agendas between lesbian and gay communities within and outside of the art world may not be addressed directly in this issue’s essays, but it underlies certain of the author’s choices and concerns. Given the relative invisibility of lesbian artists and particularly of lesbian art historians and critics, there is arguably more at stake in the writings by women. Where gay make writers can confidently assume the reader’s knowledge of key make artists and historians who are already in the canon (if not out of the closet), lesbian artists and critics have to deal with the continuing oppression of women. This oppression is at the center of Miriam Basillo’s discussion of the case of Aileen Wuornos as seen through the lens of recent lesbian art. The inhospitableness of the academy to women–regardless of sexual orientation (witness the tenure statistics)–is one of the reasons so much significant work on women and same-sex erotics has been produced outside by independent critics like Laura Cottingham. Cottingham’s essay, “Notes on lesbian,” discusses the near invisibility of lesbians and lesbian content in traditional art history.

One of the ironies of art history’s suppression of lesbian and gay content is that within the discipline the work of art is so often taken to be a closet that needs to be opened. Michael Lobel’s essay, “Warhol’s Closet,” demonstrates the way in which Andy Warhol plays with this trope, even as his supposedly manic collecting reveals the perversity that underlies the museum’s amassing and rearranging of objects. On another level, art historians often approach the work of art as a mystery that needs to be solved, or as a kind of mask, behind which is the essential identity of the artist. Unsurprisingly, the first attempts at interpreting works of art in terms of gay and lesbian erotics have taken the form of interpreting codes. My own work on Marsden Hartley and Charles Demuth involved exploring the ways their art had different meanings depending on their audiences. 4 What could have been discussed more in my book is the relationship of form to symbolic content. For example, is there a way to think of Hartley’s Portrait of a German Officer not just in terms of what it hides and reveals of a clandestine love, but as an embodiment of love itself? Hartley’s symbolic portrait was created to remember Karl von Freyburg, who had died in the early stages of World War 1. The picture is about the loss of love, and the impossibility of declaring the love between two men openly. But the painting’s transformation of flags, medals, and tassels into glorious patterns of color and line also suggests love’s fulfillment. Disturbingly, Hartley’s use of military regalia glorifies war. Yet paradoxically, the picture’s union of fragments is the opposite of the oppression and violence that is the essence of war. Hartley’s attraction to authority even as he refused to conform to its conventions was an essential aspect of gay life in the United States and Europe between the wars. But I do not want to be misunderstood. By raising the issue of form I am not postulating a gay sensibility, a set of stylistic characteristics that would be equivalent to a code. Instead, I am thinking about how the integrity and generosity of works of art might serve as a critique of the world. I am not calling for a new formalism in which we assume that good form amounts to good politics, but a reintegration of formal analysis into a investigation of lesbian and gay/queer content.

In asking for a reevaluation of what art looks like as well as what it means I am also hoping that lesbian and gay artists and art historians rethink the critical potential of traditional forms of art making. Of course, postmodernist strategies of appropriation have been and continue to be useful in unmasking institutional power. But we should be worried by how easily postmodernist modes of art making have been welcomed by the very museums and institutions they were meant to subvert. Traditional media like easel painting and art photography have recently been discredited. Their sensuousness, their use as decoration, and their ability to command high prices have been taken as complicity with an elitist art market. But if the right to love and to desire is central to lesbian and gay/queer studies, then I think we have to become more attentive to the erotics of art, past and present. For surely in art’s generosity and abundance is the model for a more loving and just world.

Returning to Duane Michals’s remarkable series of photographs, things are queer, not only because the world cannot be known and all representations are fallible, but because of the transforming process of art itself. In Michals’s beautiful photographs, queerness becomes an ideal; the circularity of the series suggests that the image is inexhaustible and unknowable. But in the end, art’s pleasures, its humor and mystery, do help us know the world in all its queerness.

Notes

1. Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Epistemology of the Closet (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990). 1

2. Adrienne Rich, “Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence,” In Blood, Bread, and Poetry. Selected Prose, 1979-1985 (New York: W.W. Norton, 1986).

3. Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, Volume 1: An Introduction, trans. Robert Huxley (New York; Vintage Books, 1978), 6-7.

4. Jonathan Weinberg, Speaking for Vice: Homosexuality in the Art of Charles Demuth, Marsden Hartley, and the First American Avant-Garde (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993).

Jonathan Weinberg, an associate professor of art history at Yale University, is a painter and author of Speaking for Vice.