Hal Fischer: Gay Semiotics

The gay culture’s new visibility has exposed a subculture developing its own myths, cultural heroes, stereotypes and sign language (semiotic). Long before the current women’s journals began picturing naked men as sex objects, gay magazines were exploring aspects of male eroticism. And since gay men needed a method to communicate sexual preferences, a sexual semiotic was developed.

Unfortunately, until recently gay culture has suffered from a scholarly stigma. If research into gay iconography has been conducted, it has largely gone unnoticed. For the purposes of this essay I have observed the gay enclaves of San Francisco and examined nationally distributed gay magazines. Two aspects of gay culture are analyzed here. First, the male fantasy; archetypal gay images as they appear in both the gay media and gay urban enclaves; second, the invention of a semiotic mode within the gay community.

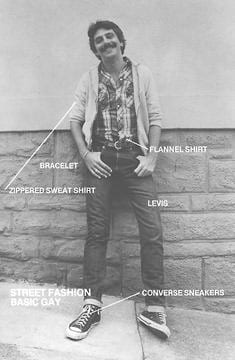

ARCHETYPAL IMAGES: Like the straight culture, gay culture has evolved a set of public, sexual prototypes. In gay magazines men are pictured in situations which were initially inspired by established male fantasies. Within the gay community certain characteristics of the fantasy have been adopted as fashion, thereby creating a ‘gay look’, i.e. Gay Prototype, the cowboy; Contemporary adaptation, flannel shirts, jeans, short hair.

The adapted items are essentially neutral in the culture at large, but form a style within the gay culture. Five basic archetypal images can be identified: classical, natural, western, urbane, and leather. The least complex, the classical and natural, are purely pictorial and exist primarily as myth structures in gay magazines, and more recently in ‘art photography’. The classical and natural have no counterpart in reality because they lack symbolic elements which can be adapted to contemporary dress. The other three have social applications in the gay lifestyle. With the exception of the urbane archetype, each prototype has its roots in cultural myths which may be construed as exclusively male. Furthermore, with the exception of the leather prototype, each archetype is based on a myth which has a social acceptability within straight cultural myths as well.

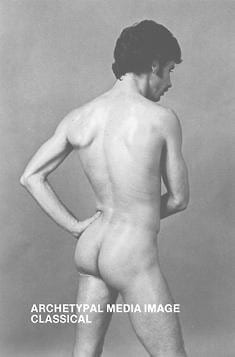

CLASSICAL: (Figure 5) The classical archetype can be understood as a modern interpretation of classical sculptural ideals. The gay media uses the classical motif rather extensively because it is universally recognized and therefore commercially viable. Here the male subject is usually presented in a highly dramatic or socially recognized artistic pose, roughly comparable to the classical, which draws legitimacy from its classical predecessors. The model is usually fully lit, or Rembrandt (edge lighting) is employed, with no scenery or props and a neutral background. Virtually the only thing needed to create this fantasy is a model whose proportions match the classical cliché.

The Greek or classical culture is a mainstay myth in gay consciousness. Greek society was essentially a male society in which both narcissism and homosexuality were accepted. Furthermore, it was a culture which contemporary society still holds onto as a paragon. Cross culturally it exists as a positive archetype.

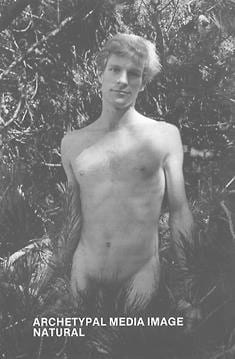

NATURAL: (Figure 6) The natural prototype originates in attitudes firmly engrained in the American consciousness. This archetype has antecedents in both American folk tradition and the arts. The natural motif is easily recognized. The model is photographed outdoors, usually in a forest or field environment with natural lighting. Unlike the classical archetype, the nature myth does not demand a specific physical “look”. Any model can be “natural” when photographed under the proper conditions. The nature archetype, like the classical myth, carries positive connotations. It implies virility, simplicity and-most important-freedom from any type of structure. The nature stereotype draws its impact from its relationship to the larger American cultural romance with nature myths.

Historically the individual in communion with nature is held up not only as an ideal, but also as a solution. References to the wilderness abound throughout literature, from Thoreau’s Walden to Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. These sources are rich with male connotations which become useful to gay culture. In Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, Huck and Jim lazily-and nakedly-float down the river. Whitman, in his poetic celebrations pays particular homage to men.

In painting as well, throughout the 19th century, we are presented with images of men in the wilderness, hunting, exploring or trading. Women seldom appear, and when they do it is usually in a minor role. Thomas Eakins devoted a great portion of his artistic energies to the male subject. He had close relationships with his male pupils: together they would go on retreats to the Eakins family farm, where the artist would make extensive photographic studies of the men wrestling, playing or posing. Some of these photographs were used as studies for paintings such as The Swimming Hole, which pictures six men (including the artist) swimming in the nude.

The 19th century natural archetype was rooted in classical ideas, but was reworked with an American subject matter. The prototype is particularly sacred to the American myth of the pioneer and of the wilderness as total freedom. Space and movement remain the answers to all problems, be it heading off to the moon, or simply hauling it down the road as Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda tried to do in Easy Rider.

In the media the nature myth reached a popular apex in the late 1960’s when the image of a naked man in front of a visionary landscape was embellished on day glo posters thoughout the country. The nature stereotype is a constant retreat when things get confusing in the real world. In advertising the nature motif is often used to offer a positive image while promoting a negative product.

Gay culture and the American culture at large share many of the same feelings toward the nature archetype. However, gay culture relates the nature motif to a mythical 19th century existence which depicted a men-only society in harmony with nature, free of rules and regulations.

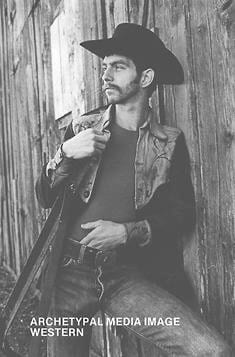

WESTERN: (Figure 7) The classical and natural archetypes operate primarily on a mythic and subliminal level, with little application to contemporary dress or appearance. The three remaining prototypes co-exist equally on a mythic level in gay magazines and on a real level in everyday gay culture.

The western or cowboy archetype can be seen as derivative of the natural myth. The archetype is recognized by articles of clothing, cowboy or western boots, jeans, flannel shirts, and in some instances hats. When the image appears in gay magazines the settings are usually imitation barns, corrals or fence posts. A typical advertisement for a gay escort service pictures a male model wearing only a hat and cowboy boots, standing in front of a plank background. He stands in 3/4 profile ‘ready to draw’. The analogy between the non-existent gun and the penis as ‘male weapon’ is obvious.

The cowboy represents the frontier and male dominated society. The bunkhouse, wide open spaces and male camaraderie have origins and parallels in the classical archetype, but are more contemporary, and widely used in TV and movies, and therefore easier to relate to. It would be unlikely for an American boy growing up in the 40’s or 50’s not to have a cowboy hero.

The machismo qualities of the western archetype are vigorously exploited by advertising. Modern cowboys are used by tobacco companies to play up masculinity and sexuality in a way that can easily be understood and emulated.

The gay media takes the archetype to its limits, playing up the image of the stud, pictured (unlike the leather archetype) in a positive and often innocent role. The western image traditionally has a heavy fantasy quotient. Society has, perhaps, begun to recognize the fact that a large number of the 35,000 cowboys roaming the range after the Civil War were finding sexual release with one another. Andy Warhol, in his film Lonesome Cowboys, used the western myth as the basis for a rather rambling plot in which the cowboys were sexually involved with one another.

The western image is popular for three reasons. First, movies and television have made it familiar. Second, the cowboy lives a ‘man’s life in a man’s world’. Third, western attire is easily translated into contemporary dress. Gay fashions (with the exception of the leather culture) tend to utilize prevailing male fashion standards. Flannel shirts, jeans, and boot are all popular within the mainstream culture. The gay culture finds these symbols useful because they assert one’s gayness, while retaining a masculine connotation within the society at large.

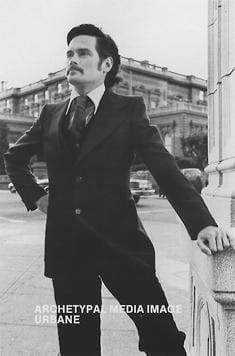

URBANE: (Figure 8) The growth of the gay culture is bringing a concern for quality into the gay media. Magazines are now appearing which include male centerfolds and essays, but which also feature quality writing oriented to the urban gay male.

The magazines have begun to promote the urbane image, a cross between stylish men’s wear and the elements of the western or leather look. The urban archetype emphasizes the gay male who is open and positive about his image and capable of functioning within the culture at large. It represents a new level of consciousness, a positive attitude towards gay culture by elements both within and outside the culture.

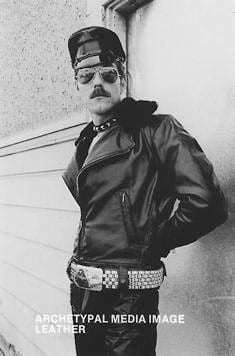

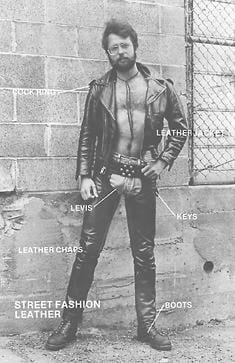

LEATHER: (Figure 9) The archetypes described so far all have their roots in myths accepted and celebrated by the mass culture. The leather cult, like its straight counterpart, is based on non acceptance or rebellion.

The leather archetype is the most easily recognized. Black leather items include everything from hoods to jackets, pants, caps and underwear. (figure 17; figure 24). Accoutrements include motorcycles, chains and various sexual items. The leather cult has its own bars, magazines and entertainments.

The leather cult was spawned by films and attitudes of the 1950’s; its primary inspirations were most likely Marlon Brando’s The Wild One, and James Dean’s Rebel Without a Cause. The leather cult is separate from mainstream gay culture because of the unconventional activities in which its members engage. While the cult adapts the motorcycle image as a proclamation of non-acceptance or separation, the leather men tend to involve themselves in private anti-social behavior (sadism and masochism) rather than public anti-social behavior.

The leather archetype has a peculiar mystique within the gay culture. Although the gay media and lifestyle do not widely publicize the leather cult, they do accept it in subtle degrees. Gay magazines which aim at a large cross-section tend to avoid the total leather look in favor of suggestion. A model in a magazine might, for example, be wearing a studded black leather wrist band or a studded belt. (figure 10)

Within the gay community black leather becomes a symbol for the unknown or the untried. It is entirely, vehemently, macho (at least in appearance and sometimes in reality). Members of the leather culture are a recognized but separate part of gay culture because of their appearance and tendency towards sadistic and masochistic activities.

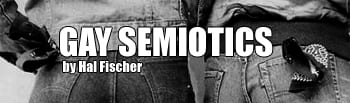

GAY SEMIOTICS: The gay semiotic, specifically the handkerchief signifier, was created in the leather community for practicality. Patrons of leather bars wanted to know who to cruise — they needed an identification system (figure 1) which would label men as passive or aggressive and also signify the type of sex act in which they wished to engage.

In San Francisco, the signs began appearing around 1971. The Trading Post, a department store specializing in erotic merchandise, began promoting handkerchiefs in the store and printing cards with their meanings. The red and blue handkerchiefs and their significance were already in existence, and meanings were assigned to other colors as well.

Traditionally western societies have utilized signifiers for non-accessibility. The wedding ring, engagement ring, lovelier or pin are signifiers for non-availability which are always attached to women. Signs for availability simply do not exist.

In gay culture, the reverse is true. Signifiers exist for accessibility. Obviously, one reason behind this is that gays are less constrained by a type of code which defines people as property of others of feels the need to promote monogamy. The gay semiotic is far more sophisticated than straight sign language, because in gay culture, roles are not as clearly defined. On the street or in a bar it’s impossible most of the time to determine a gay man’s sexual preference either in terms of activity or passive/aggressive nature. Gays have many more sexual possibilities than straight people and therefore need a more intricate communication system.

In the gay semiotic the body is divided into sides, the left representing the aggressive, the right the passive. Any sign placed on the left side indicates that the wearer will always take an active role during sexual activity. Conversely, a sign on the right side of the body indicates passive behavior. Three basic signifiers are recognized: handkerchiefs, keys and earrings. Handkerchiefs (Figure 2) are assigned meaning by color. A blue handkerchief is a signifier for anal intercourse. A blue handkerchief in the left hip pocket indicates that the wearer will assume the dominant role. Conversely, a blue handkerchief in the right hip pocket indicates that the wearer will play the passive role.

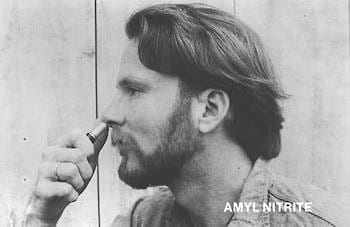

Red handkerchiefs signify behavior relating to anal/hand insertion, while black handkerchiefs indicate masochistic/sadistic tendencies. Yellow handkerchiefs represent sexual activities with the participant’s urine, or in gay jargon ‘water sports’.

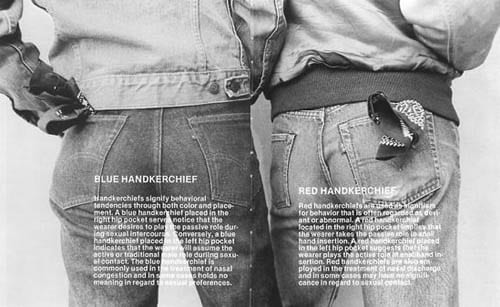

Keys (Figure 3) hung from a metal clasp attached to a belt loop are another common signifier for gay activity. While the body orientation remains constant, keys are not indicative of specific types of sexual activity.

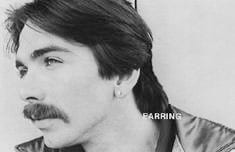

The earring (Figure 4) is sometimes employed as a sign, but is rather vague in meaning. While handkerchiefs and keys have either masculine or neutral connotations, the earring has strong feminine implications and at times is simply an object of fashion. The earring is a somewhat confused signifier, because its uses and meanings are so varied.

While gay semiotic mode is publicized, it is not necessarily practiced or adhered to within all strata of the gay community. For example, the handkerchief placed in the rear hip pocket is always a gay signifier, but is not always used as a sign for a particular activity. Interestingly the handkerchief is seen more often on the left or active side, and less frequently on the right or passive side, because gays are often reluctant to advertise their passive tendencies.

Handkerchiefs are also ambivalent signifiers because many individuals prefer to pick their roles after they pick their partners. In fact, the ‘switch hitter’ is probably more common to the gay scene than the individual committed to a particular activity.

However, the one area in which signifiers are stringently observed is the cult in which they originated. The leather culture exists as a subculture within a subculture, where the more unconventional sex acts involving sadism, masochism and water sports are practiced with frequency. Due to the variety and intensity with which the leather cult participates in these activities, the handkerchief signs are taken quite seriously.

Like any other cultural group, gay people have developed a semiotics intended both for identification and/or invisibility within the larger culture, as well as communication among themselves. As economic, political and social levels of interaction fluctuate, the uses of the language will broaden and new, more evolved — overt as well as covert — terms will come into use. As the gay community is polarized on some issues and cohesive around others, the semiotic process which helps locate in the larger culture will flourish with the interesting and undoubtedly provocative results.

ARCHETYPAL MEDIA IMAGES |

|

|---|---|

|

|

CLASSICALThe classical prototype can be viewed as a modern caricature of antique sculptural ideals. the gay media employs a classical motif rather extensively because it is universally understood and therefore commercially viable. the subject is usually presented in a highly dramatic or “socially recognized” artistic pose, roughly comparable to the classical and drawing its legitimacy from its antique predecessors. The subject is usually fully illuminated, or edge lighting is employed, with no scenery or props and a neutral background. |

|

WESTERNThe western or cowboy prototype is identified by articles of clothing: cowboy or western boots, jeans, flannel or western style shirts and in some instances hats. When the image appears in gay magazines the settings are usually barns, corrals or fence posts. The cowboy represents the frontier and a male-only society. The machismo qualities of the western archetype are vigorously exploited by advertising. Modern cowboys are used by the media to play up masculinity and sexuality in ways that are subconsciously understood by the gay populace. |

|

URBANEThe growth of the gay culture has brought about a concern for quality in the gay media. Magazines are now appearing which include male centerfolds and photo essays, but also feature quality writing oriented to the urbane gay male. The urbane prototype expressed through fashionable attire emphasizes the gay male who is open and positive about his image and capable of functioning within the culture-at-large. It represents a new level of consciousness and a positive attitude towards the gay culture by elements both within and outside the subculture. |

|

LEATHERThe leather prototype is the most easily recognized look. Black leather items include everything from hoods to jackets, pants, caps and underwear. Accoutrements include motorcycles, chains and various sexual items. In the gay media black leather becomes a symbol for the unknown or untried. It is entirely, vehemently, macho in appearance. While the other archetypes have their roots in myths accepted and celebrated by the culture-at-large, the leather cult, like its straight counterpart is rooted in non-acceptance and non-conformity. |

|

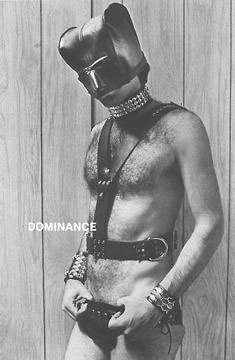

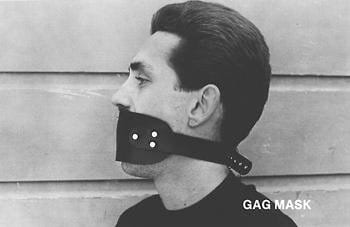

DOMINANCEDominace is achieved through the creation of an aura. In this example the aggressor has selected a black leather mask with eye and nose slits and matching black leather underwear. He also finds that a studded collar and conplementary wrist bands give his partner an added thrill. The “command torso” harness is adjustable to any chest size and has metal rings for attatchments. The aggressor’s black, hairy chest is the perfect complement to the dominance look. |

|

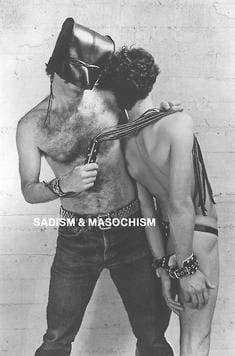

SADISM & MASOCHISMS & M activities demand structured role playing and a high level of communication between partners. In this case the M, clad only in leather jock strap and padded restraints, anticipates a whipping. The bare chested S prefers the anonymity of the hood and obliges his partner with a whipping from his specially selected cat-o-nine tails. While all this takes place in an atmosphere of good, clean fun, a lack of communication between the S and M can result in bodily harm. |

|

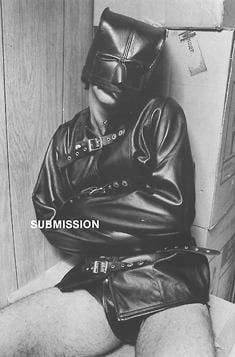

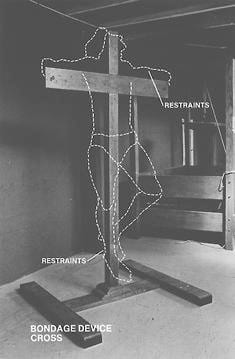

SUBMISSIONBondage creates sexual stimuli through immobilization. A number of devices are available for this purpose including wrist restraints, harnesses, and collars. The black leather strait jacket with four buckles and belted sleeves is a specialty item, guaranteed to please the most demanding S and M connoisseurs. However, economy minded individuals will find that rope clothesline and a book on sailor’s knots can provide a great deal of variety and hours of enjoyment at a minimal expense. |

|

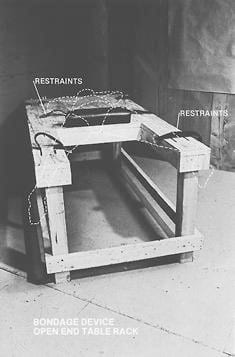

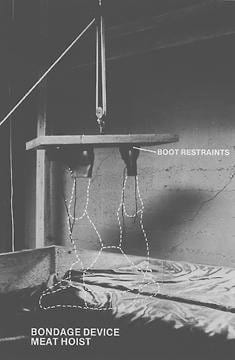

BONDAGE DEVICE OPEN END TABLE RACK |

BONDAGE DEVICE MEAT HOIST |

BONDAGE DEVICE CROSS |

HIPPIE

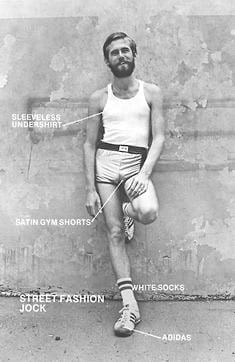

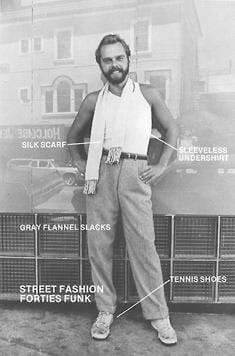

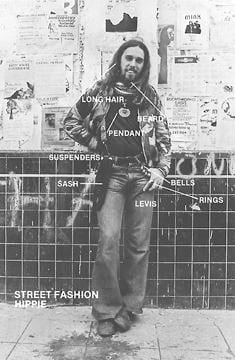

STREET FASHION |

|

|---|---|

BASIC GAY

|

JOCK |

FORTIES FUNK |

HIPPIE |

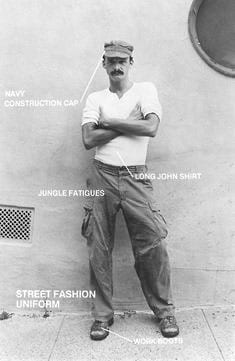

UNIFORM |

LEATHER |

ADDENDUM

In February 1977 I began work on a series of photographs which dealt with signaling devices found in the gay community. The images evolved out of my attempts to integrate the phenomena I observed in my neighborhood (Castro Street & Haight Ashbury) with my readings on structuralism.

Originally I had not planned to continue beyond the signalling photographs, but I quickly realized that from an anthropological position I had only scratched the surface of the gay experience. At that time my interest was further generated by the fact that I could not find any books or written information dealing with the visual iconography of the gay lifestyle. During this period Donna-Lee Phillips suggested that I write an essay on gay semiotics for Eros and Photography . The research and subsequent article (reproduced here) formed the nucleus for many of the photographic ideas which appear in this book.

The exhibition of these photographs and publication of Gay Semiotics have occurred at a time when gay people have been forced to both evaluate and defend their lifestyles. In the past year we have witnessed the Anita Bryant purge and continued legislative attempts to curtail human rights. We have also observed San Francisco’s incredible gay day parade of 1977 and a developing awareness on social, economic, and political levels. At this point I cannot begin to describe how these things have affected my work, except to say that I hope this book will be part of the new and growing consciousness.

Gay Semiotics could not have been created without the assistance of many individuals:

My models (Richard, Tom, Michael, Rick, Kile, Bill, Tinker, Jon, Billy, Dan, Michael, Skip, Wayne, Larry, Doug, and Steven) were not only amazingly patient, but made suggestions and criticisms which were crucial to the development of my thinking.

Nick O’Demus of the Trading Post supplied the leather apparel and restraint funiture which appear in these photographs and also provided me with information on the origins of gay semiotics.

Don Lawson and Edward de Celle of the Lawson de Celle Gallery were responsible for the first public showing of this work in August 1977.

And Donna-Lee Phillips and Lew Thomas, who in addition to presenting me with provocative theories and reading material for the past year, furnished the technical expertise to make Gay Semiotics a reality.

Hal Fischer

November, 1977

San Francisco, California

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Albert, George. The Queens. New York: Da Capo, 1975

Arguelles, Jose A. The Transformative Vision. Berkeley, Ca: Shambhala, 1975

Austen, Robert. Playing the Game. New York: Bobbs-Merrill, 1977

Benjamim, Walter. Illuminations. New York: Schocken, 1976

Brinnin, John Malcom. The Third Rose: Gertrude Stein And Her World. Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1959

Burnham, Jack. The Structure of Art. New York: George Braziller, 1971

Gallucci, Ed & Grumley, Michael. Hard Corps. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1977

Hawkes, Terence. Structuralism and Semiotics. Berkeley, Ca: University of California Press, 1977

Hobson, Laura Z. Consenting Adult. New York: Warner, 1975

Hodges, Andrew & Hunter, David. With Downcast Gays. Toronto, Ontario: Pink Triangle Press, 1974

Hunt, Morton. Gay: What You Should Know About Homosexuality. New York: Farrar-Straus-Giroux, 1977

Isherwood, Christopher. Berlin Stories. New York: New Directions, 1954

Katz, Jonathan Ned. Gay American History. New York: Crowell, 1976

Lane, Michael. Structuralism: A Reader. New York: Basic Books, 1970

Murray, Joan. Reading the Structure of a Subculture. Oakland, Ca: Artweek, August 1977

Paz, Octavio. Claude Levi-Strauss: An Introduction. New York: Delta, 1975

Perrone, Jeff. San Francisco: Hal Fischer. New York: Artforum, October 1977

Ramirez, Efren Convento. In Pursuit of Images. San Francisco: Peace & Pieces Foundation, 1976

Robbe-Grillet, Alain. For A New Novel: Essays on Fiction. New York: Grove Press,1965

Robbe-Grillet, Alain. Snapshots. New York: Grove Press, 1968

Rowse, Al. Homosexuals In History. New York: Macmillan, 1977

Sander, August. Photographer Extraordinary. London: Thames & Hudson, 1973

Schmidt, Paul, ed. Arthur Rimbaud: Complete Works. New York: Harper & Row, 1975

Thomas, Lewis C. 8×10. San Francisco: Not-For-Sale Press, 1975

Thomas, Lew, ed. Photography and Language. San Francisco: Camerawork Press, 1976

Trading Post, A Taste of Leather #7. San Francisco: Trading Post, 1976

Tripp, C.A. The Homosexual Matrix. New York: Signet, 1976

Van Vechten, Carl, ed. Selected Writings of Gertrude Stein. New York: Vintage, 1972

Walker, Mitch. Men Loving Men. San Francisco: Gay Sunshine Press, 1977