Felix Gonzalez-Torres

“Untitled”, 1995

Billboard

Dimensions vary with installation

© The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation

Felix Gonzalez-Torres (1957-1996)

In 1993, in lieu of a standard biography/bibliography, Felix chose to write a portrait of himself. This is the Biography that we have chosen to print, which is in the true spirit of this gifted artist.

1957 born in Guaimaro, Cuba, the third of what would eventually be four children 1964 Dad bought me a set of watercolors and gave me my first cat 1971 sent to Spain with my sister Gloria, then went to Puerto Rico to live with my uncle 1979 returned to Cuba to see my parents after an eight-year separation 1981 parents escaped Cuba during Mariel boat lift, my brother Mario and sister Mayda escaped with them 1978 met Jeff in Puerto Rico 1976 Gloria and I moved to our own apartment-small, but full of sunlight 1977 Rosa 1976 met my friend Mario 1979 moved to New York City 1980 met Luis at the beach 1983 received BFA from Pratt Institute 1981 and 1983 attended the Whitney Museum Independent Study Program 1987 received MFA from the International Center of Photography and New York University 1983 Ross at the Boybar 1985 Jeff gave me Pebbles and Biko, two Lilac Point Siamese cats-hardly able to support myself, and now with two cats to feed, only Jeff 1985 first trip to Europe, first summer with Ross 1986 summer in Venice, studied Venetian painting and architecture 1986 blue kitchen, blue flowers in Toronto – a real home for the first time in so long, so long, Ross is here 1987 Wawanaisa Lake: beavers, wild brown bears, Harry retrieved every buoy he sees, New York Times every morning, duck cabin 1986 Mother died of leukemia 1990 Myriam died 1991 Ross died of AIDS, Dad died three weeks later, a hundred small yellow envelopes of my lover’s ashes-his last will 1991 Jorge stopped talking to me, I’m lost – Claudio and Miami Beach saved me 1992 Jeff died of AIDS 1990 silver ocean in San Francisco 1992 President Clinton – hope, twelve years of trickle-down economics came to an end 1990 moved to L.A. with Ross (already very sick), Harry the Dog, Biko, and Pebbles, the Ravenswood, Rossmore, golden hour, Ann and Chris by the pool, magic hour, rented a red car, money for the first time, no more waiting on tables, ‘Golden Girls’, great students at CalArts, Millie and Catherine, went back to Madrid after almost twenty years-sweet revenge 1989 the fall of the Berlin Wall 1991 Bruno and Mary, two black cats Ross found in Toronto, came to live with me 1991 the world I knew is gone, moved the four cats, books, and a few things to a new apartment 1991 went back to L.A., hospitalized for 10 days 1990 first show with Andrea Rosen 1993 moved to 24th Street 1987 joined Group Material 1991 Julie moved from Brooklyn to Manhattan 1992 the forces of hate and ignorance are alive and well in Oregon and Colorado, among other places 1993 Sam Nunn is such a sissy, peace might be possible in the Middle East 1992 started to collect George Nelson clocks and furniture 1993 three years since Ross died, painted kitchen floor bright orange…

from:(Catalogue Raisonne Cantz 1997)

| Untitled (North), 1993 | Untitled, 1992 | Untitled (right billboard), 1991-93 |

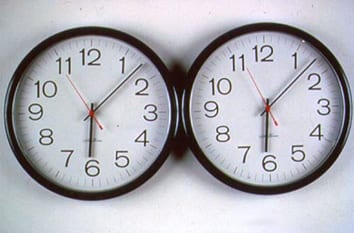

| Perfect Lovers, 1987-1990 | Untitled (Beginning),1994 | Untitled (Placebo), 1993 |

| Untitled, 1991 | Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.), 1991 |

Interview with Felix Gonzalez-Torres by Robert Storr

ArtPress

January 1995

; Pages: 24 -32

By: Robert Storr

FELIX GONZALEZ-TORRES

ETRE UN ESPION

Interview by

Robert Storr

The work of Felix Gonzalez-Torres has quickly risen to a preeminent place on the international scene asone of the most personal oeuvres in contemporary art. The great number of shows currently devoted to his output, including the major exhibition planned for the Guggenheim (17 February – 7 March, 1995) are ample proof of this attention. Criticized as being a politically correct artist, Gonzalez-Torres strikes back in the following interview, calling for a veritable guerrilla war – intelligent and undercover – against the plethora of straightforward, moralizing works of art with their angry-young-man messages. You recently took part in an exhibition in London that placed you in context with Joseph Kosuth, and the pair of you in context with Ad Reinhardt. And I was struck by the fact that instead of trying to separate yourself from previous generations, you joined with Kosuth in establishing an unexpected aesthetic lineage. Could you talk about that a little bit because on the whole, younger artists generally avoid putting themselves in such close proximity to their predecessors, especially conceptualists in relation to painters? I don’t really see it that way. I think more than anything else I’m just an extension of certain practices, minimalism or conceptualism, that I am developing areas I think were not totally dealt with. I don’t like this idea of having to undermine your ancestors, of ridiculing them, undermining them, and making less out of them. I think we’re part of a historical process and I think that this attitude that you have to murder your father in order to start something new is bullshit. We are part of this culture, we don’t come from outer space, so whatever I do is already something that has entered my brain from some other sources and is then synthesized into something new. I respect my elders and I learn from them. There’s nothing wrong with accepting that. I’m secure enough to accept those influences. I don’t have anxiety about originality, I really don’t.

READING ALTHUSSER DRUNK

How did that show come about? Joseph and I met one day somewhere downtown, and he was talking about how much he admired Reinhardt, although he was a totally different kind of artist – a painter -belonging to a different generation. It was the same thing for me with Joseph. I will never do the kind of work that Joseph has done. I’m not into Heidegger and I don’t go to the dictionary and blow up the information into black-and-white photostats. But I respect Joseph’s work a lot. I think that we in the new generation, the one that has used some of the same ideas for the advancement of social issues, owe a lot to artists of the past like Lawrence Weiner and Kosuth. In the essay in the show’s catalogue Joseph said itvery well, “The failure of conceptual art is actually its success.” Because we, in the next generation, took those strategies and didn’t worry if it looked like art or not, that was their business. We just took it and said that it didn’t look like art, there’s no question about it but this is what we’re doing. So I do believe in looking back and going through school reading books. You learn from these people. Then, hopefully, you

try to make it, not better (because you can’t make it better), but you make it in a way that makes sense. Like the Don Quixote of Pierre Menard by Borges; it’s exactly the same thing but it’s better because it’s right now. It was written with a history of now, although it’s the same, word by word. What other theoretical models do you have in mind? Althusser, because what I think he started pointing out were the contradictions within our critique of capitalism. For people who have been reading too much hard-core Marxist theory, it is hard to deal with the fact that they’re not saints. And I say no, they’re not. Everything is full of contradictions; there are only different degrees of contradiction. We try to get close them, but that’s it, they are always going to be there. The only thing to do is to give up and pull the plug, but we can’t. That’s the great thing about Althusser, when you read his philosophy. Something that I tell my students is to read once, then if you have problems with it read it a second time. The if you still have problems, get drunk and read it a third time with a glass of wine next to you and you might get something out of it, but always think about practice. The theory in the books is to make you live better and that’s what, I think, all theory should do. It’s about trying to show you certain ways of constructing reality. I’m not even saying finding (I’m using my words very carefully), but there are certain ways of constructing reality that helps you live better, there’s no doubt about it. When I teach, that’s what I show my students – to read all this stuff without a critical attitude. Theory is not the endpoint of work; it is work along the way to the work. To read it actively is just a process that will hopefully bring us to a less shadowed place.

FOR WHICH AUDIENCE

When you say what you and some of the people of your generation have done is to deal with the elements

of conceptualism that can be used for a political or a social end, how do you define the political or social dimension of art? What do you think the parameters are?

I’m glad that this question came up. I realize again how successful ideology is and how easy it was for me to fall into that trap, calling this socio-political art. All art and all cultural production is political. I’ll just give you an example. When you raise the question of political or art, people immediately jump and say, Barbara Kruger, Louise Lawler, Leon Golub, Nancy Spero, those are political artists. Then who are the non-political artists, as if that was possible at this point in history? Let’s look at abstraction, and let’s consider the most successful of those political artists, Helen Frankenthaler. Why are they the most successful political artists, even more than Kosuth, much more than Hans Haacke, much more than Nancy and Leon or Barbara Kruger? Because they don’t look political! And as we know it’s all about looking natural, it’s all about being the normative aspect of whatever segment of culture we’re dealing with, of life. That’s where someone like Frankenthaler is the most politically successful artist when it comes to the political agenda that those works entail, because she serves a very clear agenda of the Right.

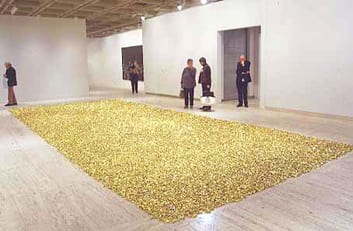

For example, here is something the State Department sent to me in 1989, asking me to submit work to the Art and Embassy Program. It has this wonderful quote from George Bernard Shaw, which says, “Besides torture, art is the most persuasive weapon.” And I said I didn’t know that the State Department had given up on torture – they’re probably not giving up on torture – but they’re using both. Anyway, look at this letter, because in case you missed the point they reproduce a Franz Kline which explains very well what they want in this program. It’s a very interesting letter, because it’s so transparent. Another example: when you have a show with white male straight painters, you don’t call it that, that would be absurd, right? That’s just not “natural”. But if you have four Black lesbian sculptors from Brooklyn, that’s exactly what you call it, “Four African-American Lesbians from Brooklyn.” What’s your agenda? Who are you trying to reach? When people ask me, “Who is your public?” I say honestly, without skipping a beat, “Ross.” The public was Ross. The rest of the people just come to the work. In my recent show at the Hirshhorn, which is one of the best experiences I have had in a long time, the guards were really in it. Because I talked to them, I dealt with them. They’re going to be here eight hours with this stuff. And I never see guards as guards, I see guards as the public. Since the other answer to the question “Who’s the public?” is, well, the people who are around you, which includes the guards. In Washington people asked me, “Did I train the guards, did I give them a lecture?” I said, “No, I just talk to them when I’m doing the work.” They said, “You know we have never been to an exhibit where the guards go up to the viewers and tell them what to do, and where to go, what to look at, what it means.” But again, that division of labor, that division of function is always there in place to serve someone’s agenda. THE POLITICAL ARENA When I was at Hirshhorn and saw the show, there was one particular guard who was standing with the big candy floor piece Untitled (Placebo), and she was amazing. There was this suburban white, middle class mother, with two young sons who came in the room and in thirty seconds, this woman – who was a black, maybe church-going civil servant in Washington, in the middle of all this reactionary pressure about the arts – there she was explaining to this mother and kids about AIDS and what this piece represented, what a placebo was, and how there was no cure and so on. Then the boys started to fill their pockets with candies and she sort of looked at them like a school mistress and said, “You’re only supposed to take one.” Just as their faces fell and they tossed back all but a few she suddenly smiled again ad said, “Well maybe two.” And she won them over completely! The whole thing worked because then they got the piece, they got the interaction, they got the generosity and they got her. It was great.

Do you think there’s a way to break the intellectual habits that result from generations of moralizing protest art. Such work is based on the idea that the artist is there to enlighten a socially benighted world, along with that comes the expectation that the artist personally be a beacon of virtue so that if, at any point, they are shown to be less than pure, then everything they say is subsequently dismissed as bogus. This has happened over and over, as if the social content of art were limited to individual ethical exercises rather than thinking of art as political and cultural probe? Let’s go to the political arena, I’ll say, the real political arena, and say that some politicians that have not been “good,” yet they have done some very wonderful things for everyone, improving the quality of life for a lot of us in a very tangible way and at the most intimate personal levels. Like some of the programs John F. Kennedy started. I’m a product of that. I went to school because of what that man started. Womanizers and drunks and all that stuff, guys with mob connections made all these changes possible so that someone like me could the get loans and go to school. That’s just one simple example of from life. Let’s move forward to a certain degree, in terms of the kind of protest art that says all Capital is bad, Bennetton is bad. We know that! We really do know that. We don’t need a gallery space to find out something we read in the news. PURITAN ANTI-AESTHETIC What about ideas of a puritan anti-aesthetic?

I don’t want that. No, between the Monet and Victor Burgin, give me the Monet. But as we know aesthetics are politics. They’re not even about politics, they are politics. Because when you ask who is defining aesthetics, at what particular point – what social class, what kind of background these people have – you realize quickly again that the most effective ideological construction are the ones that don’t look like it. If you say, I’m political, I’m ideological, that is not going to work, because people know where you are coming from. But if you say, “Hi! My name is Bob and this is it,” then they say, that’s not political. It’s invisible and it really works. I think certain elements of beauty used to attract the viewer are indispensable. I don’t want to make art just for people who can read Fredrick Jameson sitting upright on a Mackintosh chair. I want to make art for people who watch the Golden Girls and sit in a big, brown, Lazy-boy chair. They’re part of my public too, I hope. In the same way that that woman and the guard are part of my public. How do you think about the issue of engaging in explicitly social forms of art making with respect to your involvement with an activist collaborative project like Group Material? What’s the relation between the work you did with them and what you do as an individual artist? I always worked as an individual artist even when Group Material asked me to join the group. There are certain things that I can do by myself that I would never be able to do with Group Material. First of all, they are totally democratic entity and although you learn a lot from it, and it’s very moving, it’s very exacting, everything has to be by consensus, which is the beauty of it, but it is much more work. It’s worth it 100%. But as an individual artist there are certain things that I want to bring out and express, and the collaborative practice is not conducive to that. Group Material’s installations were generally a form of public address. How does that differ from what you’ve done on your own in other circumstances? Well, if you think of the stacks, especially the early stacks, that was all about making these huge, public sculptures. When I started doing this work in 1988-89 the buzzword was public art. One thing that amazed me at that the difference between being public and being outdoors was not spoken about. It’s a big difference. Public art is something which is really public, but outdoor public art is something that is usually made of good, long lasting material and is placed in the middle of somewhere, because it’s too big to be inside. I was trying to deal with a solution that would satisfy what I thought was a true public sculpture, and that is when I came up with the idea of a stack. It was before people started making scatter art and stuff like that. So when people walked into the gallery at Andrea Rosen’s and they saw all these stacks, they were really confused because it looked like a printing house, and I enjoyed it very much. And that’s why I made the early stacks with the text. I was trying to give back information, For example, there are ones I made with little snippets from the newspaper, which is one of the biggest sources of inspiration because you read it twice and you see these ideological constructions unravel right in front of your eyes. It wasn’t just about trying to problematize the aura of the work or it’s originality, because it could be reproduced three times in three different places and in the end, the only original thing about the work is the certificate of authenticity. I always said that these were public sculptures; the fact that they were being shown in this so-called private space doesn’t mean anything – all spaces are private, you have to pay for everything. You can’t get a sculpture into a public space without going through the proper channels and paying money to do that. So again I was trying to show how this division between public and private was really just words.

STATE OF CULTURE WARS

What is your guess about what the next phase of the cultural wars going to be? How will the whole NEA and censorship and multiculturalism proceed from here?

I think we’ve gone through a cycle and I sense that it will change directions somewhat, but I’m not at all sure which way. It’s going to go on for a while, but first of all, we should not call it a debate. We should call it what it is, which is a smoke screen. It is no accident. As we know, everything, that happens in culture is because it is needed. There are certain things that happen to be there for a long time but they’re not needed, culture is not ready for that. That’s not the right social condition to make them be, to make them physical, to bring them to the forefront. Everything in culture works like that. So this is all a smoke screen. I just gave this lecture in Chicago and I read all this data and tried to make sense of what happened during the eighties, during the last Republican regime, how the agenda of the right was implemented and that was an agenda of homophobia and the enrichment of 1% of the population. Clearly and simply. But it is something we love. We love to be poor and we love to have the royal class. I know that deep inside we miss Dynasty, because that gave us the hope of some royalty, a royal family in America, which we almost had. But why worry about the fact that we have the lowest child immunization rate of all industrialized nations, right behind Mexico. Why worry about that when we can worry about $150 given to an artist in Seattle to d a silly performance with his HIV blood? Why worry about $500 billion in losses in the Savings and Loan industry when $10,000 was given to Mapplethorpe? Because the threat to the American family, the real threat to the American family is not dioxin and it’s not the lack of adequate housing, it’s not the fact that there has been a 21% increase in deaths by gun since 1989.

A SMOKE SCREEN

That’s not a threat. The real threat is a photograph of two men sucking each other’s dicks. That is really what could destroy us. It makes me wonder what is the family. How come that institution is so weak that a piece of paper could destroy it? Of course, you ask yourself, why now and why this issue and you realize that something else is happening. This is a smoke screen to hide what they have already accomplished. GUERILLA WARFARE The Right is very smart. Before they had Martians; well we proved that there’s no life on Mars. Then they said the Russians were ready to invade this country, but they’re not there any longer. Fidel is sinking, so what is there left that we can have that is visual and symbolic as that – the arts. Especially the arts that have, well, homosexual imagery. And that is one thing that bugs me about artists who are doing so-called gay art and their limitation of what they consider as an object of desire for gay men. When I had a show at the Hirshhorn, Senator Stevens, who is one of the most homophobic anti-art senators, said he was going to come to the opening and I thought he’s going to have a really hard time explaining to his constituency how pornographic and how homoerotic two clocks side-by side are. He came there looking for dicks and asses. There was nothing like that. Now you try to see homoeroticism in that piece. There’s a great quote by the director of the Christian Coalition, who said that he wanted to be a spy. “I want to be invisible,” he said, “I do guerilla warfare, I paint my face and travel at night. You don’t know until election night.” This is good! This is brilliant! Here the Left we should stop wearing the fucked-up T-shirts that say “Vegetarian Now.” No, go to a meeting and infiltrate and then once you are inside, try to have an effect. I want to be a spy, too. I do want to be the one who resembles something else. We should have been thinking about that long ago. We have to restructure our strategies and realize that the red banner with the red raised fist didn’t work in the sixties and it’s not going to work now. I don’t want to be the enemy anymore. The enemy is too easy to dismiss and to attack. The thing that I want to do sometimes with some of these pieces about homosexual desire is to be more inclusive. Every time they see a clock or a stack of paper or a curtain, I want them to think twice. I want them to be like the protagonist in Repulsion by Polanski where everything becomes a threat to her virginity. Everything has a sexual mission, the walls, the pavement, everything. We’ve touched on this already, but you came up in a generation where young artists read a lot of theory and out of that has come a great deal of work which refers back to theory in an often daunting or detached way. And that has put off many people. In effect, they’ve reacted against the basic ideas because they’ve gotten sick of the often pretentious manner in which those ideas were rephrased artistically. It’s a liberating aspect of the way that most of my generation does art, but it also makes it more difficult because you have to justify so much of what you do. If we were making, let’s say, a more formalist work, work that includes less of a social and cultural critique of whatever type, it would be really wonderful. Either you make a good painting or you make a bad one, but that’s it. When you read Greenberg you can get lost in page after page on how a line ends at the edge of the canvas, which is very fascinating – I love that, I can get into that, too. But when some of us, especially in the younger generation, get involved with social issues we are put under a microscope. We really are and we have to perform that role, which includes everything. It includes the way we dress to where are seen eating. Those things don’t come up in the same way if you are interested in the beautiful abstractions that have nothing to do with the social or cultural questions. It’s part of the social construction but it has less involvement in trying to tell you what’s wrong or what’s right. These are two plates on a canvas, take it or leave it. What you see is what you get. Which is very beautiful too – I like that.

TO CONTROL PAIN

After doing all these shows, I’ve become burnt out with trying to have some kind of personal presence in the work. Because I’m not my art. It’s not the form and it’s not the shape, not the way these things function that’s being put into question. What is being put into question is me. I made “Untitled” (Placebo) because I needed to make it. There was no other consideration involved except that I wanted to make art work that could disappear, that never existed, and it was a metaphor for when Ross was dying. So it was a metaphor that I would abandon this work before this work abandoned me. I’m going to destroy it before it destroys me. That was my little amount of power when it came to this work. I didn’t want it to last, because then it couldn’t hurt me. From the very beginning it was not even there – I made something that doesn’t exist. I control the pain. That’s really what it is. That’s one of the parts of this work. Of course, it has to do with all the bullshit of seduction and the art of authenticity. I know that stuff, but on the other side, it has a personal level that is very real. It’s not about being a con artist. It’s also about excess, about the excess of pleasure It’s like a child who wants a landscape of candies. First and foremost it’s about Ross. Then I wanted to please myself and then everybody.

University Art Museum

University of California, Berkeley

Berkeley, California

Matrix is The University Art Museum’s venue for exhibiting cutting edge art.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres

MATRIX/Berkeley 161

Mid January – late March 1994

Untitled (right billboard), 1991-93

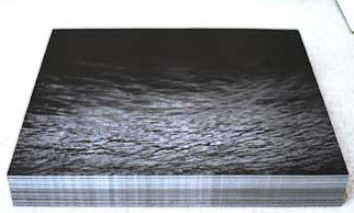

Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ MATRIX exhibition consists of two greatly enlarged black-and-white photographs and two long strings of bare light bulbs hanging from the gallery ceiling. The photographs, taken by the artist, depict birds flying against banks of clouds that are suffused with the pale light of an obscured sun. Enlarged to such a degree, the images become grainy to the point of abstraction, coalescing as an image only when viewed from some distance. As part of this exhibition, the same images are installed on actual billboards at sites throughout the East Bay. Also, in conjunction with this exhibition, there is a special insert in the UAM/PFA bi-monthly calendar: a photograph by the artist depicting the rumpled sheets and pillows of an un- made bed.

The materials and techniques of Gonzalez-Torres’ artworks are extremely modest: his use of commercially manufactured lighting fixtures and billboard prints neither astonish nor intimidate the viewer with the virtuosity of the artist’s “hand.” Rather, Gonzalez-Torres’ work is based in a more conceptual tradition that is perhaps closer to the practice of poetry than to the Western tradition of visual arts. Like a poet, Gonzalez-Torres does not reinvent language with each work, but rather utilizes the language (i.e. the materials) already available to him, recombining images and forms to create a specific effect.

While the individual materials of his work may lack much intrinsic aesthetic power, in juxtaposition and in the specificity of their placement (whether in a museum gallery or in some exterior, public site), Gonzalez-Torres’ works become charged with intense emotion. Here, in particular, the artist unabashedly lays bare an expression of awesome solitude that may strike viewers alternately as sad or soothing. There is nothing obscure about this work: its appeal to the viewer is in terms of images and symbols that are rooted in the vernacular culture. For the two photographs in this exhibition, some of the possible associations that come to mind are sky/heaven, bird/individual, bird/angel, light/wisdom, lights/angels.

Gonzalez-Torres identifies with the romantic movement of the early nineteenth century. Contrary to the common association of romanticism with a self-absorbed, anti-social stance, Gonzalez-Torres’ work resonates with that aspect of romanticism which was imbued with social consciousness. As Raymond Williams describes: “What were seen at the end of the nineteenth century as disparate interests, between which man must choose and in the act of choice declare himself either a poet or a sociologist, were, normally, at the beginning of the century, seen as interlocking interests: a conclusion about personal feeling became a conclusion about society, and an observation of natural beauty carried a necessary moral reference to the whole and unified life of man.”

Indeed, Gonzalez-Torres’ art is both by intention and by effect rooted in contemporary social conditions and comments on these conditions, albeit in an oblique and non-didactic manner. In this work, specifically, Gonzalez-Torres calls to mind both the alienation that plagues our society as well as the profound sense of loss felt for those who have died prematurely from the ravages of disease, war, and crime. While the work is open to numerous readings, its mood of solemn meditation certainly reflects, for the artist, the tragedy of his lover’s recent death from AIDS. This highly personal experience certainly lies behind the tender vacancy conveyed by the artist’s photograph of an empty bed.

In addition to his solo work as an artist, Gonzalez-Torres has been active for many years with the artists’ collective, Group Material (also including Julie Ault, Doug Ashford, and Karen Ramspacher). Like Gonzalez-Torres’ own work, Group Material, through the creation of thematically-based group exhibitions, creates bridges between aesthetic/personal/emotional and activist/public/informational modes. In 1989, Gonzalez-Torres participated in Group Material’s MATRIX exhibition, AIDS Timeline. Felix Gonzalez-Torres was born in 1957 in Güaimaro, Cuba, and currently lives and works in New York City.

Lawrence Rinder

Works in MATRIX:

Untitled, 1991-94, installation (two billboards glued to wall), dimensions and format variable. Private collection, Germany.

Untitled, 1991-94, dimensions and format variable. Berkeley and Oakland installation: silkscreen on billboard located at 6 locations, H. 10’5″, W.

22’6″. Private collection, Germany.

Detail from Untitled billboard, 1992, dimensions and format variable. Insert in UAM/PFA January/February 1994 Calendar, Vol. XVII, No. 1:

offset lithography on newsprint, 14 1/2″ x 22″. Lent by Elaine and Werner Dannheiser.

Untitled (couple), 1993, two strings, each string with light bulbs, extension cords, porcelain light sockets, dimensions vary with installation. Lent by

Mr. and Mrs. Jeffrey R. Winter.

Selected one-person exhibitions:

The New Museum of Contemporary Art, NYC ’88; The Brooklyn Museum, NY ’89; Andrea Rosen Gallery, NYC ’90 (also ’91, ’92, ’93); Neue

Gesellschaft für Bildende Kunst, Berlin, Germany ’90; Luhring Augustine Hetzler, Santa Monica, CA ’91; Massimo de Carlo, Milan, Italy ’91; The

Museum of Modern Art, NYC ’92; Magasin 3 Stockholm Konsthall, Sweden ’92; Galerie Peter Pakesch, Vienna, Austria ’92.

Selected group exhibitions:

The New Museum of Contemporary Art, NYC, The Rhetorical Image ’90; Whitney Museum of American Art, NYC, Biennial ’91; Portland Art

Museum, OR, Dissent, Difference and the Body Politic ’92; Margo Leavin Gallery, Los Angeles, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Albert Oehlen, Christopher

Williams: Théâtre Verité ’92; Musée d’Art Contemporain, Lausanne, Switzerland, Post Human ’92; Museum Fridericianum, Kassel, Germany, The

Nightshade Family ’93.

Selected bibliography:

Azgikos, Jan. “This Is My Body,” Artforum 29, no. 6 (Feb. ’91), pp. 79-83.

Deitcher, David. Felix Gonzalez-Torres (Stockholm: Magasin 3 Stockholm Konsthall ’92).

Nickas, Robert. “Felix Gonzalez-Torres: All the Time in the World,” Flash Art 24, no. 161 (Nov./Dec. ’91), pp. 86-89.

Tallman, Susan. “The Ethos of the Edition: The Stacks of Felix Gonzalez-Torres,” Arts 61, no. 1 (Sept. ’91), pp. 13-14.

Umland, Anne. Currents 34: Felix Gonzalez-Torres (New York: The Museum of Modern Art ’92).

Wye, Deborah. “‘Untitled (Death by Gun)’ by Felix Gonzalez-Torres,” The Print Collector’s Newsletter 22, no. 4 (Sept./Oct. ’91), pp. 117-19.