Glen Ligon

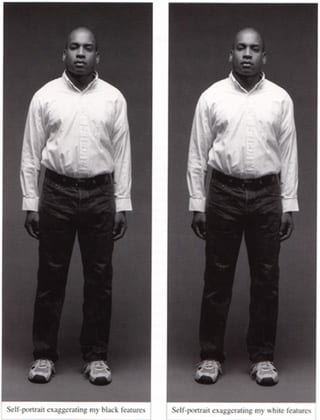

Glenn Ligon is a conceptual artist who chooses to create work in black and white as a way of pointing directly at racial stereotypes and expectations; at the same time it is a refusal to let his self-portraits be “colored.” In limiting his palette or restricting his photographs, Ligon reminds us of the polarized race relations that still plague the United States — one hundred-fifty years after the abolition of slavery.

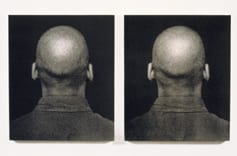

Glenn Ligon | Self Portraits, 1996 10 images, each 48 x 40 inches San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Self-Portraits, 1996. Installation view, “Glenn Ligon: New Work,” San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Borrowed Voices:

Glenn Ligon and the Force of Language

By Richard Meyer

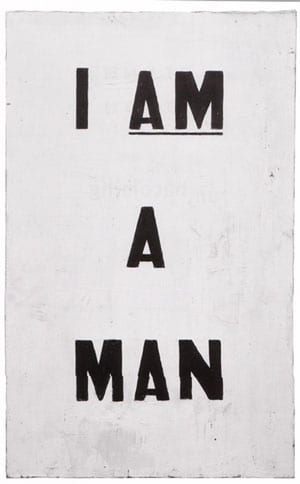

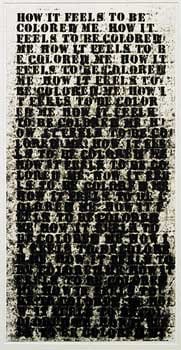

The work of Glenn Ligon mines the history of African American culture, from slave narratives to the Million Man March, from the icons of the abolitionist movement to the raunchy jokes of Richard Pryor. In the series of paintings that remain his best known, Ligon stencils black text across the surface of white, doorsize canvases. The words presented are not the artist’s own but have been borrowed from such writers as Zora Neale Hurston, Ralph Ellison, and James Baldwin. Typically, Ligon will repeat an especially charged sentence (“How it feels to be colored me,” “I am an invisible man,” “I feel most colored when I am thrown against a sharp white background”) until it verges, through the force of excess paint, on illegibility. The resulting pictures set up a series of dialogues between visibility and erasure, between the naming of color and its painterly absence on the canvas, and between the “black space” of the stenciled letters and the “white space” into which they increasingly bleed. For all the seeming dispassion of Ligon’s formal method (monochrome palette, stenciled letters, repeated words), his text paintings are supercharged with affect. They speak a first-person voice of black subjectivity while registering the denial and relentless silencing of that same voice.

An artist who is always reading, Ligon has said that he “wants to make language into a physical thing, something that has real weight and force to it.” (1) He listens hard to specific forms of both spoken and written language, to the inflections of vernacular and period use, and to the subtleties of syntax and style. Equally as important, Ligon looks hard at the material forms and mechanical reproduction of language, at printing methods, paper formats, and typefaces. In a 1993 series of prints entitled Narratives, for instance, Ligon mimicked the rhetoric and typography of nineteenth-century slave narratives while replacing the details of the text with information drawn from his own biography:

THE LIFE AND ADVENTURES OF GLENN LIGON, a Negro who was sent to be educated amongst white people in the year 1966 when only about six years of age and has continued to fraternize with them to the present time.

Ligon historicizes the language of self-description to draw out the trauma, but also the ironies, of modern black experience. Rather than situating the slave narrative securely in the past, the artist insists on the continuing relevance of that narrative to contemporary black life, including, and especially, his own. The power of Narratives lies largely in the way it studies (rather than simply appropriates) its source material, in the way it updates such texts as Incidents in the Life of Slave Girl and Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglas while carefully retaining the period format of their frontispieces.(2)

By routing slave narratives into a series of late twentieth-century self-portraits, Ligon complicates the status of those narratives as documents of authentic black experience. As we are reminded throughout Narratives, antebellum accounts of the slave’s life were prepared, edited, and often fictionalized to conform to the perceived desires of a white audience. Because it was illegal for slaves to learn to read or write, and because the veracity of the slave’s word was so frequently questioned, slave narratives were a almost always prefaced by extended testimonials as to their authenticity. In many cases, these testimonials were penned by white abolitionists who had transcribed the narrative or otherwise helped to secure its publication. (3) Narratives draws out the tension between the first-person voice of the slave and the white reader for, and by, whom that voice was recorded. In a print entitled “Black Like Me, or The Authentic Narrative of Glenn Ligon, A Black Man,” the artist appends a long–and hilariously long-winded–testimonial, which is signed, “Yours, very truly, A WHITE PERSON.” By framing the white person as a generic category, an undifferentiated type, Ligon satirizes the white authentication of black experience while suggesting that it was the very category of whiteness, rather than the testimonial of any one abolitionist, that carried the power of legitimization. (4)

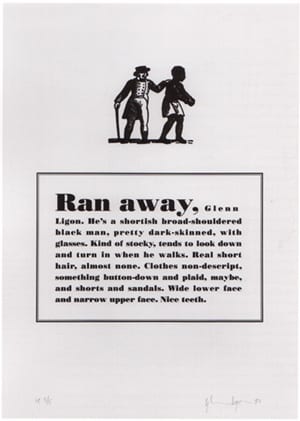

In Runaways (1993), a series of prints created in conjunction with Narratives, Ligon revises fugitive slave posters of the midnineteenth century by inserting various descriptions of himself in place of a the runaway slave. The descriptions were drawn from ten friends of the artist, each of whom was asked to provide a verbal account of Ligon as though reporting his disappearance to the police. The texts that emerged from this process combine the casual language of physical appearance with the brute force of slavery:

RAN AWAY, Glenn Ligon. He’s a shortish broad-shouldered black man, pretty dark-skinned, with glasses. Kind of stocky, tends to look down and turn in when he walks. Real short hair, almost none. Clothes nondescript, something button-down and plaid, maybe, and shorts and sandals. Wide lower face and narrow upper face. Nice teeth.

That last phrase, “Nice teeth,” set off as its own sentence, resonates with the blunt language of the slave auction block. The entire print, in fact, closely mimics the format of its source material, down to the crowning visual icon of a white man in hat and topcoat restraining a shackled, half-naked black slave. In Runaways, as in Narratives, Ligon insinuates the historical legacy and language of slavery into a set of otherwise current descriptions of himself. In so doing, he situates slavery as a symbolic force that continues to reverberate within contemporary black life.

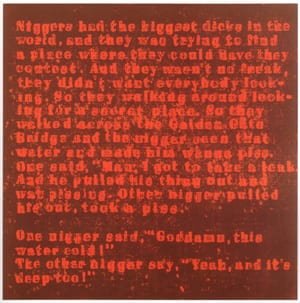

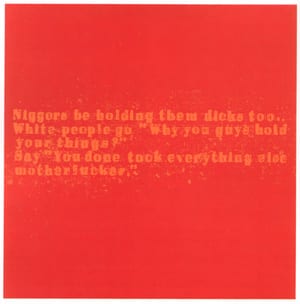

In both Narratives and Runaways, Ligon locates his art at the intersection of oral and written language, at the meeting place of verbal description, textual transcription, and historical source material. Tensions between the written and spoken word inflect a great deal of Ligon’s art, including several projects that take up far more recent examples of black representation than the slave narrative. In Cocaine (Pimp) and Mudbone (Liar) (1993), Ligon appropriates two jokes popularized by Richard Pryor in his stand-up routines of the seventies and early eighties. These jokes, which play on the image of the black man as well-endowed and obsessed with his own sexual power, blithely speak in the vernacular language of the street. As presented by Ligon, the improper grammar, syntax, and spelling of these jokes constitutes merely one aspect of their larger “impropriety.” For one thing, Pryor’s jokes are meant to be heard rather than read, listened to rather than looked at. In their original context, the jokes depend on Pryor’s vocal performance for their success, on the rhythms and intonations of this particular delivery. (5) Resituated as text paintings, the jokes become dissociated from Pryor’s voice and linked instead to the viewer’s. It is the viewer who must now read this script, who must mouth, however silently, these words. In rewriting Pryor’s jokes as text paintings, Ligon forces us to consider the vehemence of their stereotypes, the rage barely veiled beneath their humor, and the power of their obscenity in the face of a dominant (white) culture that simultaneously desires and dehumanizes black manhood.

In a review of the 1993 Whitney Biennial, the Village Voice described Glenn Ligon as “a closet aesthete.” (6) The description was used to contrast the visual elegance of Ligon’s work with the self-conscious crudeness of several other artists in the show. Yet, the comment also implied another layer of meaning. Ligon’s contribution to the 1993 Biennial, Notes on the Margin’s of the “Black Book,” was his first work to deal with an explicitly gay theme. In it, Ligon juxtaposes Robert Mapplethorpe’s nude black men with a wide range of textual commentaries, including those of artists, politicians, Christian commentators, queer theorists, and drag queens. Ligon multiplies voices within Notes, not in order to create a happy plurality of diverse perspectives but to reveal how Mapplethorpe’s black male nudes function as a cultural screen onto which both fears and fantasies are projected. Rather than situating Mapplethorpe’s work as either a positive image or a negative stereotype of black sexuality, Ligon directs our attention to the ways the Black Book functions as a symbolic battleground on which conflicting claims–about race, desire, disease, art, and freedom–are registered.

Notes on the Margin of the “Black Book” inaugurated a moment in Ligon’s career in which the artist increasingly came to focus on the relationship between race and sexuality, including, but not limited to, his own. “In a sense, my work ‘outed’ me,” says Ligon. “I had already been out [to friends and family] but not in the public, professional world in that way.” (7) As this remark suggests, the process of coming out is not a simple declaration of sexual identity–made once, duly noted, and then left behind–but an ongoing series of negotiations between the gay subject and the multiple social worlds (e.g. private and public, familial and professional) in which he or she circulates. These negotiations are further shaped by the varying degrees of recognition and refusal, of silence and (half-) spoken acknowledgement that the gay subject encounters in response to “coming out.” Notice, for example, how the Voice’s description of Ligon as a “closet aesthete” suggests without specifying, a gay aspect to the artist’s work, how it displaces the homoerotic content of Notes on the Margin of the “Black Book” onto the plane of formalism.

Yet, such a displacement is not an entirely erroneous or regrettable one. Throughout his career, Ligon has suffused his work with a high degree of formal resolution and pictorial presence. The symmetry and elegance of Notes, for instance, is central to its critical mission, not least because Mapplethorpe’s photographs are themselves so painstakingly composed. Ligon began Notes on the Margin of the “Black Book” by jotting down his responses to the nudes on the pages of a personal copy of the book. The piece was born, the, from Ligon’s direct criticism/defacement of Mapplethorpe’s work. Yet rather than present his own “notes” in the finished project, Ligon turned to a wider, and more volatile, chorus of commentators. Instead of superimposing the language of these commentators directly onto Mapplethorpe’s photographs, Ligon centered two rows of framed and printed texts between the two tiers of black male nudes. Ligon’s wraparound grid of word and image respects, rather than violates, the formal logic of Mapplethorpe’s work. Notes on the Margin of the “Black Book” opens a space, at once critical and visual, between Mapplethorpe’s nudes and the voices that respond to them.

It is not coincidental that Notes, Ligon’s first explicitly homoerotic work of art, was also his first photo-text installation. “I think it is easier,” Ligon observes, “to speak about sexuality through specific photographic representation [than through painting or text].” (8) While he continues to produce paintings with oilstick, stencils, and canvas, Ligon now works with a wide range of other materials, including vintage gay porn, family snapshots, old issues of Jet magazine, thrift-shop furniture, and photographic portraits taken at Sears. In A Feast of Scraps (1994-98), Ligon inserted pornographic photographs of black men, complete with self-invented captions (“Mother knew;” “I fell out;” “It’s a process”), into photo albums of family snapshots, some of which depict Ligon’s own family. In these albums, unbidden erotic fantasies and sexual stereotypes of black men suddenly, and altogether spectacularly, take their place beside vacation snapshots, graduation photographs, wedding showers, birthday celebrations, and church baptisms. A Feast of Scraps renders visible that which must be kept hidden, left unspoken, or otherwise repressed within traditional records of domestic and familial life.

Throughout his career, Ligon has investigated those moments when identity seems to slip or give way to its own erasure. For a recent installation entitled Day of Absence (1996), the artist combined larger-than-lifesize self-portraits resembling mug shots with four monumental silkscreens of news photographs of the 1995 Million Man March in Washington D.C. Day of Absence simultaneously registered Ligon’s awe in the face of the march and his disappointment that the collective visibility of black men was purchased at the price of other absences; namely, those of black women and (many) black gay men, including the artist himself. The full title of the 1995 event, “The Million Man March/Dau of Absence,” referred to the fact that black women wishing to support the march were asked to absent themselves from work on that day. By borrowing the second half of that title for his installation, Ligon emphasizes the ways in which (male) presence was tied to (female) absence, both at the march itself and in the newspaper photographs documenting it.

In Hands, one of the silkscreens murals in Day of Absence, a sea of black hands reaches upward as thought grasping or waving at something beyond the bounds of the visual field. The specific context for this photograph was a collective pledge in which march participants were asked to rededicate themselves to the cause of the family. In Ligon’s mural, however, this context gives way to larger series of symbolic tensions between presence and absence (the hands vs. the men to whom they belong), between abstraction and figuration (the streaky expanse above vs. the outstretched fingers below), between the terms of political identity and those of invisibility (the mass of black men vs. their fragmentation and disappearance).

In another of the Day of Absence murals, a huge banner is hoisted above a mass of silhouetted heads and upraised fists. Apart from the wind holes that have been punched through its surface, the banner is entirely blank, an expanse of seeming emptiness. To create this mural, Ligon not only cropped and dramatically enlarged his source photograph, he digitally removed the slogan, “We’re Black and Strong,” imprinted on the banner. By eliminating these words from the image, Ligon inserts absence at the core of the collective spectacle of the Million Man March. “Who,” the empty banner now seems to ask, “is rendered invisible by this public moment of black male solidarity?” Having removed “We’re Black and Strong” from the banner, Ligon retrieved the slogan to serve as the title of the mural. The slogan is absented from the visual field only to resurface, like the return of the repressed, on a wall label or catalog checklist.

From his earliest text paintings to his most recent installations, Ligon has challenged the apparent transparency of language by changing the intended conditions of its display and reproduction. These changes have resulted in language that is difficult, and sometimes impossible, to see. As Ligon himself observes, “I’ve always taken text to the point of disappearance in my work.” (9) The artist uses disappearance to figure the limits and absences that lie at the heart of identity and to suggest that individual subjects never align neatly with the overarching terms of race or sexuality. .Glenn Ligon teaches us that the material force of language, the legacy of the borrowed voice, may register most strongly at the very moment of it sown vanishing.

1. Cited in Roberta Smith, “Lack of Location Is My Location,” The New York Times (June 16, 1991), 27.

2. Ligon consulted an archives of typography on the southern tip of Manhattan in order to match the period style of antebellum slave narratives. According to the artist, he used about twenty-five different typefaces for Narratives, some of which were common only in the nineteenth century (e.g. Orleans, Egyptian) and some of which continue to appear in printed materials today (e.g., Palatino, Century Schoolbook). For Ligon, “Theidea was the mix. The typefaces don’t match any one, original narrative exactly; they are a mix of typographical conventions from the period.” Glenn Ligon, personal correspondence with the author, September 29, 1996.

3. On the literary form of the nineteenth-century slave narrative, including the issue of authentication, see Charles T. Davis and Henry Louis Gates, Jr., eds., The Slave’s Narrative (Oxfordshire and New York: Oxford University Press, 1985).

4. Black Like Me is the title of a 1961 nonfiction bestseller by John Howard Griffin, a white writer, who, with the help of skin-darkening steroids and sunlamp treatments, traveled throughout he South as a black man and then published his experiences as an exposé of racism. In using that same title within Narratives, Ligon suggests how the experience of an “authentic blackness” is continually claimed by, and framed for, white subjects.

5. The primacy of the jokes as spoken language is further suggested by the fact that Ligon transcribed them from an LP recording of Pryor’s live stand-up routines rather than from a written source.

6. Peter Schjeldahl, “Missing: The Pleasure Principle,” The Village Voice, (March 16, 1993), 34.

7. Glenn Ligon, personal correspondence with the author, July 22, 1966.

8. Ibid.

9. Cited in “An Interview with Glenn Ligon and Gary Garrels, March 15, 1996,” Glenn Ligon New Work, exhibition brochure (San Francisco: Museum of Modern Art, 1996), unpag.

Richard Meyer is an assistant professor in the Department of Art History at the University of Southern California and a fellow at the Getty Research Institute for the History of Art and the Humanities. His book, Outlaw Representations: Censorship and Homosexuality in American Art, 1934-94, has recently been published.