Tee Corinne: Picturing Cancer in Our Lives

SCARS, STOMA, OSTOMY BAG, PORTACATH

: PICTURING CANCER IN OUR LIVES

by Tee A. Corinne

CONTENTS

Making Relationships Visible

Crisis

My Beautiful Friend

Beverly’s Leavetaking

Later

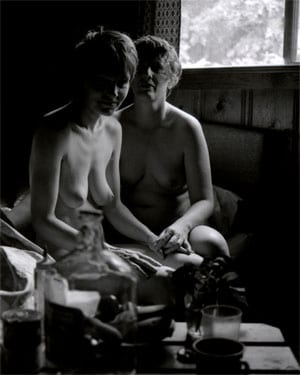

MAKING RELATIONSHIPS VISIBLE

In 1975, the year in which I most fully came out, I started making self-portraits that combined my own image with that of a lover. Photographer Honey Lee Cottrell (see Nothing But The Girl: The Blatant Lesbian Image) was my beloved at that time, and together we explored ways to make images that ìreadî as lesbian. In some of these pictures, I am nude and she is partially clothed. In one, I have my hand on her thigh and am looking into the camera as she looks at me.

In the early 1980s, after a separation of a year and a half, I made photographs of myself with Caroline Overman shortly after we became lovers for the second time. The relationship was wildly sexual and, at least to me, the pictures I made of us together, nude in hotel and motel rooms, convey this quality.

Sometime later I came into possession of a photograph of my grandmother Mabel (Carnes, Unland, Meares), taken around 1910, when At the time, she was a widow with a small child. In the picture, she is sitting on the floor leaning back against the legs of a woman seated in a chair. They were holding hands, facing the camera with looks of such complicity that they took my breath away. When I asked her about the other woman in the photo, she told me her name was Gertie Bance (Lance? Vance?). She said that Gertie was a handsome woman who never married and moved to California. I am sure they were lovers.

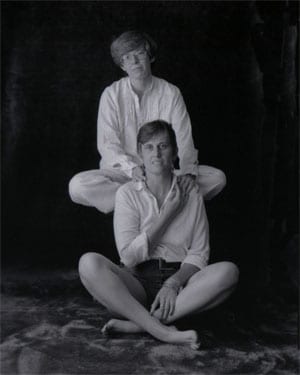

In the mid-1980s, with Lee Lynch, an author and yet another of my lovers, images which referenced that photograph of Mabel and Gertie, images in which I am shown sitting on the floor with Lee behind me.

My relationship with Beverly Anne Brown spanned the years from 1989 to 2005. Beverly loved appearing in double portraits with me and we often played in front of the camera. Frequently we used a mirror so that the picture would announce not only our lesbianism, but also that one of the subjects was the photographer.

As a rural activist and director of a non-profit organization, Beverly was cautious about allowing nude photographs to be made of her. When she was preparing to have a hysterectomy in 1992, however, she asked me to photograph her body before the surgery, but not print the photographs at that time, and I complied.

In 2003, after emergency surgery, she was diagnosed with metastasized colon cancer. Again, she had me photograph her in the nude. This time she stressed the importance of showing the scars, the stoma where her intestines now opened out of the left side of her abdomen, the ostomy bag which collected her body waste, and the porta-cath, above her right breast, which permitted easy access to her vascular system. She knew these images were important for other women to see. She wanted to show what happened to her body in order to demystify the results of having colon resection surgery, of using a body appliance like an ostomy bag, and of having a porta-cath inserted under oneís skin.

I continued taking pictures of her and of us, clothed and nude. For me, the strongest image in this series I arbitrarily colored blue. In it, we are naked, facing the camera. She is in front wearing her glasses as she almost always did. The ostomy bag is clearly visible. My hands are on her shoulders. It is titled “The Saddest Picture Iíve Ever Made.”

CRISIS

Almost exactly one year after Bev’s diagnosis, we came to a different kind of crisis. She said she had fallen in love with someone else. That someone was unavailable as a lover, but important as a friend.

We struggled forward, took photographs of one another, talked, argued, cried.

After a while, we reached a point of resolution, a place from which we could go on.

Two years after the initial diagnosis, Beverly decided to move to a city that was four hoursí drive from our shared home. The reasons for the move were complex. Some were professional: the move permitted her to continue working on projects about which she cared deeply.

For the first six weeks, we talked on the phone every day, as we had talked every day during the years of our life together. Then we talked twice a week. Finally, there was a call every Sunday. She was an amazing conversationalist: entertaining, knowledgeable and connected, always interested in what others were doing and thinking.

MY BEAUTIFUL FRIEND

Seven months after Beverly left, I drove north to see her. We had visited in person only once since she had moved out. I thought I was going to visit her to say goodbye. What happened was a closure and an opening as well. We had been estranged and we were no longer.

Earlier in the week, I had e-mailed her to see if it was all right for me to come, but she hadn’t responded. The messages being sent out by the organizer of her caretaking, M.B., were dire and implied imminent demise. My friend Jeanne encouraged me to just go, as did Beverly’s brother, Ron, who suggested I arrive shortly after he would. I knew he would help me get in if anyone should try to bar my way.

The drive takes four hours, during which I considered different scenarios. What if some woman met me at the door, arms crossed, and blocked my way? In the past, Beverly had made a list of all the people she wanted to be protected from. Would I now be on that list?

I arrived early enough to use the bathroom at a local coffeehouse and pick up a cold soda. At Beverly’s duplex, Ron and his wife, Sharon, came out of the front door as I approached. They told me Beverly was just then getting dressed. I followed them back inside. K., M.B.ís partner, was sitting in Beverly’s reclining chair holding a drooling infant. Beverly is a cleanness freak and has never been fond of babies. I wondered if she had changed in major ways.

Another friend came in, greeted me, and told me that Beverly was so changed that she had been shocked when she saw her. She told me, sotto voce, that Beverly had told her if I turned up I should be welcomed.

Beverly walked in using a cane. She was much changed and quite yellow brown but did not look nearly as bad as I had expected. Her eyes were bright and excitedly looking around. Her face lit up when she saw me. I can’t remember now if I got up and gave her a hug. I think I did, but relief was my overwhelming experience, relief that she was happy to see me and also that she was not exactly at deathís door yet.

K. went, taking the baby with her. Beverly looked at the tissues left behind and asked her brother to put them in the garbage, wash his hands, and bring her a glass of water. She was so much the same at her core that I almost laughed. Did her eyes really twinkle as she looked at me, a look that was almost conspiratory?

PHOTOGRAPHS

Small talk. I was bored. I told her I had brought my camera and would like to take pictures. She said good, that she had been trying to get others to take photographs of her, but no one would. I set up my tripod and took several close-ups of her face. She asked everyone to leave and come back in half an hour. She had me lock the front door then started taking off her clothes. She had lost a lot of upper body mass and the jaundice extended to her waist. From there down she was swollen and distended from fluids not being cleared from the body. There were feces in her ostomy bag, but I told her not to worry about it. I could PhotoShop it out later if I needed to.

She stood, turned for me, walked across the room, turned again. I took one hundred and fourteen pictures in less than half an hour. We finished. I helped her dress. She sat in her chair. The night before, her mother had called me unexpectedly, wanting to know if I had seen Beverly lately. When I told her I was going up the next day, she asked me to give Beverly a hug for her. I told Beverly this. She agreed to the hug.

I knelt before her and put my arms around her. She put her cheek against mine. One of us said, “I love you.” The other said, “I love you.”

She said, “Sometime I just miss you holding me.”

“Ditto,” I answered.

PORTLAND ART MUSEUM

I unlocked the door. People came back in. I said I would leave, but asked if I could return in the evening. Beverly said that Ni Aodagain would be there after 5 pm and I might want to visit with her. I agreed to come back between 5 and 6.

Then I drove to the Portland Museum of Art to see the new wing. Beverly and I had always enjoyed going to museums together and I wanted to be able to tell her about it. She had tried to find other museum-going companions but complained about how slow they walked or the way they stopped to read all of the wall texts.

I had about an hour and a half before the Museum closed, but I am good at speeding through exhibits, stopping only when something really catches my eye. The newly-acquired Clement Greenberg collection was fabulous, made up of all those New York-based artists whom he helped to fame by writing about them. I saw a woman reach out and tug at a piece of wood on a Louise Nevelson sculpture. No alarm went off. What is going on here?

I went to the bookstore and found a postcard of Beverly’s favorite Marsden Hartley painting which is in the older section of the museum, then I went to visit the Hartley and other beloved images including some beautiful Japanese prints.

I ate food that I had packed for the trip: energy bar, soy milk, peanuts, sunflower seeds. Beverly was sleeping when I returned. Ni Aodagain and I talked. When Beverly joined us, it was obvious that she wanted to know what was going on and to be part of it. She put the Hartley postcard on the table near her and looked at a book on Washington Women Artists that I had bought.

Later, she was sitting up on the side of her bed to eat and take meds. I sat down next to her and lightly rubbed her back. Remembering what she had said earlier, I sat near enough that our bodies could touch. She leaned her face into my hair. “You still use the same shampoo,” she said, with obvious pleasure.

She appeared to be nodding out, so Ni Aodagain asked her if there was some reason that she didn’t want to lie down and go back to sleep. “Yes,” she said. “Tee’s here.”

I encouraged her to lie down and told her I would stay. She asked Ni Aodagain to leave us alone. I asked Beverly what she wanted and she said, “Tell me about the museum,” and I told her about all of the New York School paintings, but also the large, early Joan Brown impasto and how surprising it is to me that she has been dead for fifteen years. I described the six- or seven-foot Leonard Baskin block print of a standing nude male holding a bird. I’m sure he did the initial drawing with brush and ink, then cut around the interlacing marks, creating an image of beauty and delicacy and power. I told her that I missed going to museums with her, missed having her to talk art with. “Me too,” she said.

“I love you,” I said.

“Me too,” she said.

All this time I had been holding her arms lightly, touching her, keeping contact. She drifted off to sleep and I went on sitting there, tears running down my face. Went out and Ni Aodagain held me and we sat briefly outside so I could cry, then came back in where we could hear her if she wanted anything.

LATE IN THE EVENING

Beverly woke and came into the living room. I had been told that she wasn’t eating, but she had an appetite and wanted ravioli. The evidence in her ostomy bag showed she had been eating something. I found potstickers in the freezer, but she wrinkled her nose. “Too much meat,” she said. I asked if she wanted the kind of cheese ravioli which she used to keep in our refrigerator. “Yes,” she said.

“We’ll get you some tomorrow.” She ate chocolate ice cream, soup, fruit.

Another friend came over to change her ostomy bag and I thought about how glad I was that other people are taking care of all these details. I’m glad that Beverly gets mad at other people for making her take her medicines, and not at me.

I thought about the person who has been going around saying Beverly told her that she had accomplished all she wanted and that she was ready to go. Crap. This may be true in the short term, that knowing she was going to die soon, Beverly set out to accomplish everything she could with the time and energy she had left. But Beverly was a woman who started and ran a popular education non-profit organization, and wrote books and essays. She wanted to make a major impact on the world. And she wanted recognition. She often talked with me about wanting to receive a MacArthur Award, sometimes referred to as the MacArthur Genius Award, fifty thousand dollars for each of three years with no strings attached. The money would have been nice, but she wanted the acknowledgment, the validation, the peer group affirmation as well. Part of the sadness of the current situation, for me, is that she has surrounded herself with people who donít even know what a MacArthur Award is.

I would ask if she wanted me to leave and she kept saying she wanted me to stay. She would become agitated if she thought I was going. I left around eleven and went to stay a few blocks away with the sister of a southern Oregon friend. That night, I lay awake thinking and watching the patterns of branches and leaves on the tree outside the window, the moon moving across the sky. I thought about the word reconciliation. How unexpected that we were now, so simply, reconciled, as if the seven month separation had been a chasm that we leapt across. Yesterday I was single and thinking I might soon have another lover. Beverly had broken up with me almost a year earlier although she had not moved out at that time. After my afternoon and evening with her, I felt connected again, fully engaged.

SUNDAY MORNING

In the morning, her room smelled of urine and I mentioned this. She said she was embarrassed about it, that Ni Aodagain would wash the sheets.

The night before I had put on gloves and washed dishes. Beverly laughed. ‘You know how to do it right,’ she said. I know how she likes dishes washed because I like them done the same way, lots of suds and hot water. I washed counter tops, rinsed dirty milk and soy milk containers, combined bags of garbage. Perhaps someone is coming on Monday to clean and straighten. Perhaps it isnít important. Beverly, along with always caring about hygiene, was also incredibly messy. This house is an accurate reflection of that, but at home she always wanted cooking and eating surfaces to be clean.

Some time during that second morning of my visit she was standing near her bed looking at me. ‘I was going to ask you to come,’ she said. We just stood there, looking at one another. The distance between us, perhaps six feet, seemed larger, not smaller, by her statement. Yet I was glad to know that my intuition had been right, that what she hadnít been saying over the phone for two weeks was that she wanted me to come. Stubborn women, we are, and proud, strong qualities which can also get in our way.

Beverly went to the bathroom to try to pee. Ni Aodagain and I sat in the living room where Ni Aodagain told me about her trip to New Orleans and how she was working out things with her lover. After a while, Ni Aodagain called into the bathroom to ask Beverly if she was all right.

“Yes,” she answered, “I’m enjoying listening.”

THE BATH

Ni Aodagain started doing laundry. Between us, we did four loads. Beverly announced she wanted to bathe and she wanted me to help her. She turned and looked at me and asked if that was all right.

“Yes.”

Those end-of-life intimacies are so dear. I remember helping my grandmother Mabel bathe when she was in her eighties and being surprised at how unselfconscious she was. I felt like it was a gift that she would reveal her body to me and felt the same way about Beverly wanting me to help with her bath. What she really wanted to do was wash her genitals and legs where the urine had dried.

I sat with her a long time as she relaxed enough to urinate. When she finished, she washed her hands and asked me to hand her a paper towel from the shelf. She said, ‘I couldnít get them to keep things clean enough,’ meaning she had tried keeping her own cloth towels separate, but that other people would use them, so she had resorted to paper towels.

“I knew what you were doing with the paper towels as soon as I saw them,” I said.

She put her arm around me and leaned against me. “You know me,” she said. “These people,” she pressed her lips together and shrugged toward the rest of the house, “they donít really know me.” She looked at me and smiled wryly. “You donít know everything about me, but you know who I am.”

“You donít know everything about me either,” I said. She brushed her lips across mine. It was one of two kisses she gave me, testing, teasing, territorial. Each was as soft as a birdís wing, swift and gentle and then it was gone before I could even react. I remembered all the other kisses, all the other ways she had been with me over those many years, my beautiful, smart, funny friend.

“It is so hard,” she said, “being hovered over.” She made a face. “So hard being made into an object, a thing.” We had discussed this before, the distaste she had for people wanting to help by fawning over her, using her and her illness to fulfill some kind of need of their own.

I finished drying her off and helped her into her old blue robe.

RESOLUTIONS

Driving home, I thought about the people who had told me to cut her off, cut her out of my life and move on. These include a counselor who kept pushing me to say that Beverly was being abusive to me, that I had been in an abusive relationship. To me, Beverly was dying. She was angry and confused and lashing out and I was there. As Charlotte said, “Poor baby, she is scared to death.” I thought also of the friends who said that Beverly had made her choice to leave me and that I should let go, too. If I had listened to them, I would not have had this last incredible weekend with her. She died five days later.

BEVERLY’S LEAVETAKING

On October 27, 2005, the Thursday after my weekend visit with Beverly, I felt her presence as I walked my dog in the back field. Later, Jane Mara called to tell me Beverly had died a few minutes before ten am. I wrote a brief message containing Mara’s information and sent it by e-mail to friends and acquaintances. When I came to one name that I wasn’t sure I should send the message to, the woman she had fallen in love with, I paused, wondering if it would be better for this person to learn the news from someone else. The lights blinked, then went out and came on again.

I remembered that Beverly and a friend had made an agreement that if one of them died and came back, they would try to signal to the other that they were there by blinking the lights. “OK,” I said to her, “I won’t send this one.”

The electricity didnít waver the rest of the day.

For hours, however, I had the sense of Beverly being present with me and that we were talking, although most of the time no words were being spoken. I had yet another chance to tell her how much I loved her. She was a warm presence and seemed jubilant. I was arranging to have a wake that evening, phoning and e-mailing our friends. In the early afternoon, Jeanne Simington called to ask if I needed help cleaning and preparing for people to come over. I said, “No. Beverly is here. I’m enjoying her company. I’ll call if she leaves.”

At ten minutes to four, I knew she had gone and called Jeanne to accept her offer of help.

The following day, as I was driving over the two-thousand foot Mt. Sexton Pass, the Rogue River watershed spread out before me, I was thinking about how I was going to have to come out to yet another class about my lesbianism and about Beverly’s death, or I would not be able to teach effectively that day. I was also thinking about how scary this was. First I felt her presence, then it was as if she slipped into my body just under the skin behind me. I felt her stretch out her arms along my arms and wrap her fingers along with mine on the steering wheel. In my mind I heard her say, “Don’t be afraid. I am here. I am OK.” She repeated this until I was near the foot of the mountain.

I regard these visitations as gifts and am grateful for the final flutterings of her indomitable spirit.

LATER

I had begun Photoshopping the images of Beverly and me three months before she left and continued modifying these images up to and beyond her death. Four months after Beverly died, I was diagnosed with a tumor in the liver caused by cancer of the bile ducts. I had less chance of living than a coin toss would give me.

Triage. What could be discarded, what was most important? I have chosen to complete this collaborative project and share it via a cd with text. It is a passionate work, a final act of love.