Robert Mapplethorpe

b. 1946, Floral Park, N.Y.; d. 1989, Boston

Robert Mapplethorpe was born November 4, 1946, in Floral Park, New York. He left home in 1962 and enrolled at the Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, in 1963, where he studied painting and sculpture and received his B.F.A. in 1970. During this time, he met artist, poet, and musician Patti Smith. She encouraged his work and posed for numerous portraits when they lived together in Brooklyn and in the Chelsea Hotel in Manhattan, a gathering place for artists, writers, and musicians in the early 1970s.

It was not Mapplethorpe’s original intention to be a photographer, and from 1970 to 1974, he mainly made assemblage constructions that incorporate images of men from pornographic magazines with found objects and painting. In order to create his own images for these collages, Mapplethorpe turned to photography, initially using a Polaroid SX-70 camera. Interested in portraiture, Mapplethorpe worked as a staff photographer for Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine. He also produced album covers for Smith and the group Television, and at the same time photographed socialites and celebrities such as John Paul Getty III and Carolina Herrera.

Two of Mapplethorpe’s friends were influential in his continuing exploration of photography as a means of art making. He met John McKendry, Curator of Prints and Photography at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, in 1971. The curator bought Mapplethorpe his first camera and persuaded him to take up photography full-time. Mapplethorpe traveled to Europe for the first time with McKendry, where he was introduced to many of the collectors who later became sitters for portraits. Curator and photography collector Sam Wagstaff, whom he met in 1972, became Mapplethorpe’s friend and eventual lover, encouraging the photographer’s development, gallery associations, and career course. They remained close until Wagstaff’s death in 1986.

Mapplethorpe had his first substantial shows in 1977, both in New York: an exhibition of photographs of flowers at the Holly Solomon Gallery and one of male nudes and sadomasochistic imagery at the Kitchen. Mapplethorpe’s diverse work—homoerotic images, floral still lifes, pictures of children, commissioned portraits, mixed-media sculpture—is united by the constancy of his approach and technique. The surfaces of his prints offer a seemingly endless gradation of blacks and whites, shadow and light, and regardless of subject, his images are both elegant and provocative. In the mid-to-late 1980s, returning to the sculptural use of photography seen in his early assemblages, Mapplethorpe created sensual diptychs and triptychs of photographs printed on fabric and luxurious cloth panels. In 1988, four major exhibitions of his work were organized: by the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; the Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; and the National Portrait Gallery, London. Mapplethorpe died due to complications from AIDS on March 9, 1989, in Boston.

The Institute of Contemporary Art’s retrospective continued to travel after Mapplethorpe’s death. Although the exhibition had sparked no controversy at its first two venues, the threat of right-wing objections to the photographs of S/M and homoerotic acts prompted officials at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., to cancel the show two weeks before its scheduled opening. The exhibition instead traveled to the Washington Project for the Arts, Washington, D.C., where it received record attendance.

Imaging Sadomasochism:

Robert Mapplethorpe and the Masquerade of Photography

by Richard Meyer

July 10, 1991

We should not…underestimate the signifying power of the spectacular subculture, not only as a metaphor for potential anarchy “out there” but as an actual mechanism of semantic disorder, a kind of temporary blockage in the system of representation.1

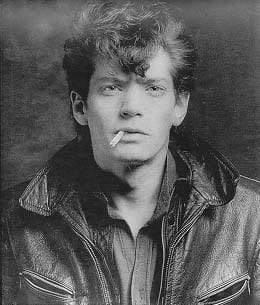

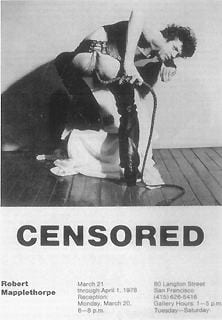

In the spring of 1987, 80 Langton Street, an alternative art space in San Francisco, mounted an exhibition of Robert Mapplethorpe’s photography. The show consisted of 19 black and white photographs cataloguing a spectrum of gay male sadomasochistic practices including penis piercing, latex bondage, single and double fist-fucking, and anal penetration with a bull-whip. An image of this last practice was the only self-portrait in the exhibition and was, not incidentally, selected as the gallery announcement for the show (fig. 1)

Figure 1. Robert Mapplethorpe, Self-Portrait, 1978 (Gallery announcement, “Censored” exhibit at 80 Langton Street). Photograph copyright 1978 The Estate of Robert Mapplethorpe.

The exhibition’s titled, Censored, referred to the curatorial circumstances surrounding and suppressing Mapplethorpe’s work at the time: After attempting without success to show his explicit s/m photography in New York, Mapplethorpe secured an agreement from the Simon Lowinsky gallery, a commercial space in downtown San Francisco, to exhibit that work along with his portraits and still-lives. Shortly before the slated opening of the show, however, the Lowinsky gallery “edited” out the most explicit of the s/m images, belatedly declaring them unfit for commercial exhibition. 80 Langton Street then stepped in, agreeing to exhibit the suppressed work on the proviso that it would not be sold via their exhibition. 2

In that the 80 Langton gallery was located just off Folsom street, the center of San Francisco’s leather scene, we could say that the censorship of Mapplethorpe’s s/m photography resulted in the return of the work to the space of its subculture. Certainly the newfound authenticity of the “Censored” exhibit–its fringe venue just around the corner from the Ramrod, the Brig, and the South of the Slot–was called upon to produce the show as an avante-garde event, one to which members of both the commercial art world and San Francisco’s high society were welcome. Listen, for example, to the description of Censored’s opening night reception which appeared in the San Francisco Art Dealer’s Associated Newsletter:

A fascinating cross-section of San Francisco society, and visitors from elsewhere, drank wine and bottled beer as they congratulated the New York photographer on his exhibition of photographs which explore the world of sado-masochism and its ritualistic trappings. Among those in the crowd, rubbing shoulders with the men in black leather, were popular ceramic artist Anita Mardikian, art collector Byron Meyer, University Art Museum Director James Elliot, male model Peter Berlin…San Francisco art dealers Simon Lowinsky, Ursuls Gropper [and so on]. 3

The clubbiness of this insider account might give us some pause in celebrating Mapplethorpe’s resistance to the commercial censorship of his work in 1978. It is Mapplethorpe, after all, who straddles the “world of sado-masochism” and that of the art-market, forming the singular overlap in that “fascinating cross-section.” And it is Mapplethorpe who is celebrated as the avatar of the erotic transgressions he photographs, the gay male artist engaging in the wild side of subculture in order to frame (and tame) its image for the gallery crowd. Patrons of the art circuit may now “rub shoulders” with the “men in black” while safely installed within the chic propriety of the art-opening. 4

The Censored exhibit would thus seem to fulfill the conventional function of documentary photography, namely the construction of an Other (whether victim, freak or specimen) for consumption by a culturally dominant, implicitly normative viewing audience. Martha Rosler describes the signifying procedures of such “concerned” photography as follows:

Documentary testifies…to the bravery or (dare we name it?) the manipulativeness of savvy of the photographer who entered a situation of physical danger, social restrictedness, human decay or combinations of these and saved us the trouble. Or who, like the astronauts, entertained us by showing us places we never hope to go: War photography, slum photography, “subculture” or cult photography, photography of the foreign poor, photography of deviance…5

As I have already suggested, this passage is descriptive of the “Censored” exhibit in significant ways: Mapplethorpe’s photography did recover gay sadomasochism from the sites of its subcultural practice and bring it back to the avante-garde “safe space” of the alternative art gallery. Even perhaps especially at the present moment, we should acknowledge Mapplethorpe’s commodification of gay subculture and his complicity with the procedures of the commercial art market. 6

Yet the fact that the Mapplethorpe’s s/m photographs sated the art market’s desire for a documentary “shock of the new” (or, as one critic would have it, a “shock of the black and blue” 7) does not eradicate the subversive valence and resistant pull of the project as a whole. While Mapplethorpe and his dealers were clearly manipulating a sexual subculture to economic ends, there were other pressures applied by his images of gay sadomasochism, ways in which they could not be–and still can not be–dismissed as so much subcultural profiteering of avante-garde exploitation.

I will suggest that Mapplethorpe, far from framing gay sadomasochism as the curious object of “concerned” photography, calls upon the intrinsic theatricality of s/m to stage the artifice and very masquerades of photography. 8 At their best, Mapplethorpe’s images of gay sadomasochism subvert the conventions of documentary by emphasizing their insufficiency as indexical records of subculturally experience. Far from “saving us the trouble” of going there ourselves, Mapplethorpe’s work announces the impossibility of ever knowing, of ever fully entering, the site of gay sadomasochism through photography.

Consider, for example,the way that the 1979 photograph of Helmut (figure 3) emphasizes in art-studio backdrop, that framing swathe of fabric, the elegant if unlikely stance of the model atop a pedestal. Mapplethorpe’s portrait glosses the codes not so much of gay sadomasochism as of art photography, of its preparations and beautifications. The formalist play with light and shade is insistent here and unapologetic, the leather jacket becoming blackest, for instance, when it overlaps the white muslin fabric behind it. Yet Mapplethorpe has been careful not to abstract the image out of all erotic specificity–the spreading of Helmut’s legs, the leather tie string which delimit ass from thigh, the suggestion of jerking off made by the placement of the right hand–these details will assert themselves should the viewer become too interested in photographic chiaroscuro or abstraction for abstraction’s sake. In denying visual access to Helmut’s face, cock, and hands. however, Mapplethorpe’s photograph refuses to depict an explicit practice of masturbation or to portray Helmut as a leatherman with any highly individuated identity. 9 Rather, the image is a portrait of the leather paraphernalia itself and the way it is erotically embodied–we might even say modeled–by one practitioner.

As with Helmut, Mapplethorpe’s 1978 portrait of Joe (fig 4) is not concerned with catching its subject in spontaneous sexual activity but with describing his erotic costume: the strap-on tube extending from the mouth, the ridges of the rubber hood, the studded collar, the industrial gloves, the sheen and torsion of the latex uniform. The premeditation of Joe’s pose–the fact that he has donned his latex and is stilling his body for Mapplethorpe’s camera–is emphasized by the visual evidence of the image. This is no vérité realm of the street or the sex-club but an acknowledged artistic set-up, the studio space of bare floorboards and benches, of backdrops and strobe lights.

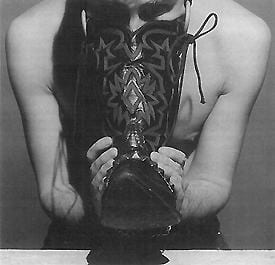

Even less than Helmut or Joe, does Mapplethorpe’s Untitled photograph from 1978 (fig 5) abstract its model out of the specificity of his sexual subculture. Indeed, it appears that the sitter has here become subordinated to his s/m fetish, as though through the very posturing of his body, he is attempting to conform to the demands of the cowboy boot. Consider the rounding over of the shoulders, the loss of the lower part of the face, the way in which the body, however we trace its contours, continually returns our gaze to the boot. Here again, Mapplethorpe has exploited the fetishistic capabilities of photography–the way it can deploy light and texture and cropping to isolate and eroticize an object–and crossed them with the fetishes of gay sadomasochism.

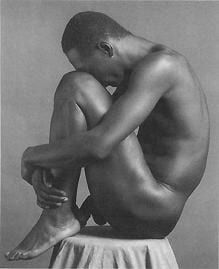

It is on just this point that I would distinguish Mapplethorpe’s portraiture of white s/m practitioners from his later series of black male nudes. In the s/m work, fetish objects and sexual paraphernalia mark the body of the model and signify his particular erotic trip: we may not be offered much information about Helmut but we do know that the harness, biker jacket, and boots are an erotic masquerade of his own choosing, just as we know that Joe’s latexwear is his and so on. The sheer diversity of the erotic props and paraphernalia on display in the s/m project asserts that Mapplethorpe is cataloguing a collective subculture, not merely his own desires or favored practices as part of that subculture, But in Mapplethorpe’s images of black male nudes, in the 1981 portrait of Ajitto, for example (fig 6), the model’s body is stripped of any marker of sexual identity or subjectivity–no traces here of the black man’s own erotic investments or fetish objects. Kobena Mercer and Isaac Julien have rightly observed of these photographs that,

As all references to a social, political, or cultural context are ruled out of the frame…the images reveal more about what the eye/I behind the lens wants to see than they do about the relatively anonymous black male models whose beautiful bodies we see. 10

Wherein the s/m pictures Mapplethorpe frame the erotic costume and sadomasochistic equipment of other white gay men, in the series of black male nudes, the model himself becomes the erotic paraphernalia, the very fetish of Mapplethorpe’s camera.

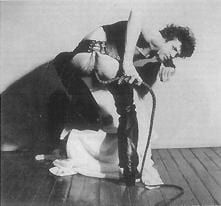

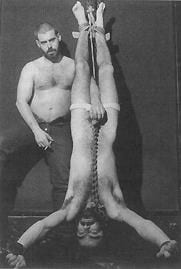

In turning back to the s/m project, I want to suggest that Mapplethorpe’s insistence on the premeditations of photography obtains no only to his portraits of individual practitioners but to those of sadomasochistic couples as well. Although it is in portraits of the s/m couple that the we might most anticipate depictions of sexual exchange, it is precisely here that Mapplethorpe most pointedly refuses that depiction. 11 The subjects of Mapplethorpe’s Elliot and Dominick (fig 7), for example, self-confidently present their erotic positions and equipment to the viewer. But even as Dominic is strung up and enchained by the apparatus of sadomasochistic and even as Elliot grabs both his own crotch and that of his submissive partner, neither man seems enthralled by the sexual act. It is as though they are waiting, perhaps resentfully, for the camera to absent itself so that the pleasure-session might begin or resume. Through the frontality of their stance and the certainty of their look, Elliot and Dominick project a resolute awareness of their roles, not only as sexual master and slave, but as subjects before the camera’s stilling gaze. Rather then enact a pretense of photographic transparency, the couple insist upon the artifice of their pose, challenging our spectatorial power to see and freeze them by signifying their agency in allowing a prepared, patently limited view of their sadomasochistic “image”.

To ground my claim that Mapplethorpe’s photographs draw a visible distance from the conventions of “subculture photography”, I will compare Dominick and Elliot to a photograph of gay s/m which might properly be called documentary: Mark Chester’s 1982 image of two men at a San Francisco sex club which accompanied an Advocate exposé on gay s/m entitled “To the Limits and Beyond” (fig 9). Note that the two men pictured are seemingly oblivious to the presence of the camera. that their spectacular fucking has been caught in media res though also from some distance, and that the subordinate details of the image–long and obscuring shadows, crushed mattress, tangle of chains–signify as random and spontaneous registered. Such are the visual codes which testify to an authentic documentary adventure, to the photographic capture of gay sex “beyond the limits.” Such are the codes which a photograph like Mapplethorpe’s Elliot and Dominick avoids at all costs.

Figure 7. Robert Mapplethorpe, Elliot and Dominick, 1979. Copyright The Estate of Robert Mapplethorpe.

If Mapplethorpe measures a distance from the conventions of documentary photography so too does he avoid the typical strategies of s/m pornography. Compare Elliot and Dominick to a soft-core porn photograph from the 1987 Son of Drummer magazine (fig 9). 12 In the Son of Drummer image, the anonymous models produce a fantasy of spontaneity and erotic release for the desiring gaze of the beholder. As viewers, we are invited to disregard the material production of the image (the presence of the photographer, the lighting of the scene, the hire and costuming of the models) so as to take more consummate pleasure in its erotic content. Apart from its assignment of sexual dominance and submission, the photograph offers no subjectivity or particular identity to the male models it displays. And indeed, even the men’s s/m roles appear reversible since both models are similarly outfitted for sex (tit-clamps, leather harnesses and hoods) and are, so far as one can tell, physically identical. Unlike this fantasy image of muscular, spontaneous sadomasochism, Mapplethorpe’s Elliot and Dominic both insists on the specific identity of its sitters and emphasizes the artifice and premeditations of photography.

Figure 8. Mark I. Chester 1982.

photo © Mark I. Chester

Slot, Rm 329

from the series, City of Wounded Boys & Sexual Warriors, 1982

The self-conscious staginess of Mapplethorpe’s s/m project is perhaps best characterized by his 1979 portrait of Bryan Ridley and Lyle Heeter (fig 10). In this image, Mapplethorpe exploits a mismatch between the couple’s sadomasochistic outfitting and their domestic interior, between their leather, chains, and master/slave hierarchy on the one hand and their wingback chair, oriental rug, grasscloth wall covering, and white antlers endtable on the other. This disjunction not only defuses the leather machismo of Ridley and Heeter, it also asserts that neither their erotic costume nor their domestic context–neither their chains nor their faux-rococo table clock–are sufficient metaphors of their identity. The spectacular contradictions of this image undo any interpretive move which would essentialize Ridley and Heeter in or as their sodomasochistic roles.

In terms of the photograph’s surprising overlay of sadomasochism and domesticity, consider the way in which the couple’s stance mimics a conventional marriage-portrait pose, with the dominant partner standing behind his seated and submissive mate. For an example of this pose in its more conventional format, we may look to Cecil Beaton’s photograph of Queen Elizabeth and the Prince Consort taken on the occasion of the Queen’s coronation in 1953 (fig 11). Even in the Beaton image, however, the standard positions of (male) dominance and (female) subservience are revised insofar as the Queen’s superior authority is signified by the elaborate regalia which unfurls from her seated position and by the marginalized position of the Prince within the visual field. Needless to say, Mapplethorpe’s portrait provides a far more radical revision of the marriage pose than to Beaton’s since the “husband” is now a leather daddy who restrains his strapping male mate with a leash of chains in one hand and a gently brandished riding crop in the other.

Figure 10. Robert Mapplethorpe, Bryan Ridley and Lyle Heeter. 1979. Copyright The Estate of Robert Mapplethorpe.

While Ridley and Heeter clearly signify their respective roles of erotic dominance and submission, each man is equally dominant–or better, defiant–in the face of the camera. The couple seem to be warning us that although an economy of top and bottom exists between them, neither man will readily submit to the gaze of the beholder, The intensity of their look out at the camera was necessary, I think, if the photograph was to avoid condescending to it sitters. We can imagine how easily the contradictions of the image might otherwise have framed Ridley and Heeter as deluded or pathetic.

Figure 11. Cecil Beaton, Queen Elizabeth II’s Coronation, 1953. Copyright Cecil Beaton/Camera Press/Globe Photos, Inc.

We can imagine, for example, how a photographer like Diane Arbus might have handled the scene. Arbus’s 1963 photograph Widow in Her Bedroom (fig 12), a portrait which similarly pivots around the relation of sitter to domestic space, helps clarify the choices made by Mapplethorpe in Bryan Ridley and Lyle Heeter. In Arbus’s photograph, the bedroom clutter and Orientalized collectibles of the widow seem to frame her freakishness, to incarcerate her within it. Notice, for example, the way the widow’s vase and bureau appear to dwarf her body, nearly to crowd her out of the room. Now compare how Mapplethorpe’s couple preside over their space and see to dictate its scale, how securely Ridley inhabits his large wingback chair, for instance, and how well Heeter’s body fills the gap formed by the parted curtains. Or contrast the widow’s utter indecision about how to sit in her chair–about how to pose for Arbus’s camera, really–with the certain stance and confident look of Ridley and Heeter. Mapplethorpe’s image admits no disdain for its subjects, none of that Arbus certainty that the sitter will always be bottom for both the photographer and the viewer.

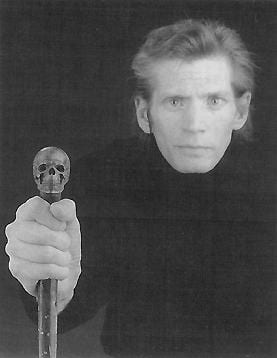

I would like to return, finally, to the Self-Portrait with bull-whip (fig 13) because I consider it Mapplethorpe’s most ambitious attempt at cross-referencing the codes of sadomasochism with those of art photography. The bravado of the self-portrait derives in large part from the spectacle of it anality and from the fact that the asshole on offer is the photographer’s own. Within the history of art, one is hard-pressed indeed to recall another self-portrait, whether painterly or photographic, which represents its artist as anally penetrable. In lieu of the conventional self-portrait’s claim to phallic mastery and professional self-regard, Mapplethorpe’s image insists on the sadomasochistic potentials and pleasures of the artist’s opened asshole. If, as Guy Hocquenhem has argued, “the anus has no social position except sublimination…[it] expresses privatization itself” 13 then Mapplethorpe’s Self-Portrait with bull-whip might be seen as a radical desublimation of the anus, a publicizing of the asshole and its erotic possibilities.

But even as the Self-Portrait articulates Mapplethorpe’s sadomasochistic identity, it reminds us that such an articulation is occurring within the prepared space of studio photography, of white walls, varnished floorboards, and draped chairs. By these lights, the fact that Mapplethorpe is at once the agent and object of anal penetration, at once fucker and fucked, may be read as referring to the procedure of making a self-portrait, of being at once the productive subject and the receptive object of photography. In short, the reflexivity of Mapplethorpe’s auto-penetration might be said to stand in for that of his auto-portraiture.

To extend this reading of the image, consider the way in which Mapplethorpe’s bull-whip snakes not only out of his body but out of the visual field, leading from his opened asshole to the beholder’s position of gazing. Might we not see the bull-whip as a metaphor for the apparatus of photography, a surrogate cable or extension cord tying Mapplethorpe’s posed body to the clicking camera off-frame? 14 If so, we could then interpret Mapplethorpe’s cupped left hand as mimicking the action of triggering a shutter-release. Read in this way, the bull-whip, a fetish object of s/m, stands in for the technologies of photographing the self, technologies implied by the metaphor to be fetishistic.

And yet, if the bull-whip is an instrument of sexual pleasure and penetrability, the very composure of Mapplethorpe’s expression seems at odds with it. It is though he is performing anal-penetration without seeming to experience it, or at least without offering the traces of that experience to the viewer’s gaze: there is no erotic release, no register of sexualized pain, no expressive evidence of the fact of being fucked. Instead, Mapplethorpe seems consummately in control of his appearance before the camera. And if his gaze acknowledges that he is is being caught (by his camera, by us) in the act of anal penetration, it also signifies his mastery over both the photograph and the sentient body depicted in it. 15

I argued earlier that Mapplethorpe’s most compelling work on s/m refutes the documentary distance between photographer and photographed, between the empowered subject and the curious object of documentary vision. There is, however, a quite different distance on which the 1978 Self-Portrait insists, namely, the distance between Mapplethorpe’s erotic practice of sadomasochism–say at the Mineshaft of The Anvil–and his masquerade of it in the studio, for the camera. What we are offered in the Self-Portrait is not a documentary image of gay sadomasochism but an acknowledged simulation of it, a performance of auto-penetration which visually glosses Mapplethorpe’s own claim that “sex without the camera is sexier.” 16

In the 1978 Self-portrait as in most of the images in the s/m project, Mapplethorpe is after something rather more ambitious than a documentary fiction of subcultural verisimilitude. In photographing the paraphernalia of sadomasochism while allowing its practioners to turn away from, or better, to look resolutely at the camera, Mapplethorpe stages gay s/m as an erotic theater whose players determine their own props and costumes, their own pleasures and script; a theater whose best performances occur beyond the frame of art photography and are therefore not accessible to the avante-garde viewer in search of Otherness.

Dick Hebdige writes,

What distinguishes the visual ensembles of spectacular subcultures from those favoured in the surrounding culture [is that] they are obviously fabricated [and] they display their own codes or at least demonstrate that codes are there to be used and abused. In this they go against the grain of a mainstream culture whose principal defining characteristic…is a tendency to masquerade as nature. 17

The achievement of Robert Mapplethorpe’s s/m project is that it displays the codes and erotic fabrications of gay sadomasochism all the while acknowledging, indeed actively calling into metaphoric use, the masquerades of photography.

FOOTNOTES

1 Dick Hebdige, Subculture, The Meaning of Style (London: Methuen, 1979) 90.

2 The Censored episode in San Francisco should be read as a pre-history of the recent and far more repressive censorship of Mapplethorpe’s work: the July1989 cancellation of The Perfect Moment, a full-scale retrospective of Mapplethorpe’s career, by the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D. C. (the show was subsequently revived by the Washington Project for the Arts, an alternative arts space, and then travelled to Berkeley, Cincinnati, and Boston); a punitive reduction in federal funding to the National Endowment for the Arts in the amount of $45,000–the sum of the grants awarded by the NEA to the Mapplethorpe retrospective and to Andres Serrano, another photographer whose work was deemed “obscene” by members of Congress; new restrictions on the NEA’s funding procedure based on the perceived content and “decency” of the work under consideration (the restrictions have since been repealed; and, in April 1990, the temporary closure of the The Perfect Moment by Cincinnati police and the indictment of its local exhibitor on obscenity charges–charges for which the defendant was tried and finally exonerated.

Curatorial information concerning the “Censored” show was related to me by Renny Pritikin, director of the New Langton Art gallery, in a phone interview on November 11, 1989 and confirmed by Robert McDonald, former board member of the 80 Langton Street gallery, in a phone interview on November 14, 1989.

3 Rita Brooks, “Censored,” San Francisco Art Dealer’s Associated Newsletter (unpaginated), May/June 1978.

4 Indeed, Simon Lowinsky, the very dealer who initially suppressed Mapplethorpe’s work is named on the list of prominent guests and in one of the photographs accompanying the notice, Lowinsky and Mapplethorpe are seen posing together for the opening-night camera, the former in jacket and tie, the latter in full leather.

5 Martha Rosler, 3 Works (Halifax: Nova Scotia: Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1981) 73.

6 The status of Mapplethorpe’s photography is no less paradoxical today than it was in 1978: even as it is now censored and censured, Mapplethorpe’s work, at up to $35,000 per print, defines the very apex of the contemporary photographic market. The recent battle over the putative “indecency” of Mapplethorpe’s work served, among other purposes, to inflate the market value of that work. See Grace Glueck, “Publicity is Enriching Mapplethorpe Estate” The New York Times, April 16, 1990: B1.

7 See David Herskovits, “Shock of the Black and Blue” Soho News (May 20-26, 1981): 9-11.

8 Gay sadomasochism is here understood as consensual erotic practice between members of the same sex in which the roles of power and powerlessness are rendered explicit and performative. The word “performative” is here meant to call attention to the intrinsic theatricality of gay sadomasochism and especially to the use of erotic props and fetish paraphernalia (leather and latex, clamps and whips, masks, harnesses, hoods, boots) and to the sexualized, stylized role-playing of top and bottom, master and slave, father and son, cop and criminal, etc.

For more on the theatrics of gay sadomasochism, see Don Miesen, “SM: A View of Sadomasochism,” Drummer 10, No.87: 15-17, 100-103 and Jeffrey Weeks’ Sexuality and Its Discontents: Meanings, Myths, & Modern Sexualities (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul): 236-41. For an excellent discussion of the theatricality of lesbian s/m see Pat Califia’s “Unraveling the Sexual Fringe: A Secret Side of Lesbian Sexuality,” The Advocate, December 27, 1979, 19ff.

9 Although the viewer is, of course, free to imagine the frontal view which the image denies: my own such view sees that Helmut, now in the midst of jerking off, is taking a hit of poppers, hence the crook of his left elbow as that arm reaches upward and the droop of his head as it receives the amyl.

10 Kobena Mercer and Isaac Julien “Imaging the Black Man’s Sex” Photography/Politics: Two, 1987 reprinted in Male Order, Unwrapping Masculinity (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1988) 143-144.

11 Mapplethorpe’s now notorious Jim and Tom, 1977-78, a photograph of two men engaging in “water sports” in a Sausalito bunker, is the obvious exception to this tendency. See Robert Mapplethorpe (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1988): 63.

12 Son of Drummer was a special edition of Drummer magazine, the premier gay porn publication devoted to leather and s/m. My selection of figure nine as a comparison to Mapplethorpe’s work was prompted by the fact that the issue of Son of Drummer in which it appears also reproduced a portfolio of Mapplethorpe photographs from the “Censored” exhibit.

See Son of Drummer (1978): “The Robert Mapplethorpe Gallery”: 14-17 and (for figure 9) “Color Shots from–The Room’s: David Warner’s Hot New Leather Film”: 5.

13 Guy Hocquenhem, Homosexual Desire, trans. Daniella Dangoor (London: Allison & Busby, 1978) 83.

14 I am indebted to Susan Scott Parrish for this formulation.

15 According to Susan Sontag, “I once asked Mapplethorpe what he does with himself when he poses for the camera, and he replied that he tries to find that part of himself that is self-confident.” In “Certain Mapplethorpe’s,” preface to Certain People (Pasadena: Twelvetrees Press, 1985): unpaginated.

16 This was Mapplethorpe’s response when asked whether he derived sexual pleasure from photographing gay sadomasochism. Quoted in an unpublished transcript of a public discussion of the “Censored” exhibition held at 80 Langton Street, April 1978, and later cited by Robert McDonald in “Censored,” The Advocate June 28, 1978, Issue 244: 21 (Second Section).

17 Hebdige: 191-192.

CENSORED

Robert McDonald

from The Advocate

“I am a man; nothing human is alien to me.” This statement by the Roman playwright Terence (190 – 159? B.C.) would have been a fit epigraph for the first uncensored exhibition of photographs by New York artist Robert Mapplethorpe.

Internationally renowned for his society (“Jet Set”) portraits and fashion ads, Mapplethorpe has experienced many difficulties in finding an exhibition space for his most recent works: images of the gay S & M scene. Even in “open-minded” cities like New York and San Francisco, commercial galleries and public museums alike have turned him down. They have shown the portraits (a nude Patti Smith, for example), his studies of flowers, even the relatively “soft-core” pics–men in leather and chains, bondage, full frontal nudity–but not the “hard core” stuff.

No wonder! “Conventional” viewers, whether straight or gay, might find them brutal and dehumanizing, including as they do images of FF–even double FF!–rimming and mangling.

Mapplethorpe, considering the nature of the art support system and its patrons, realistically never expected a public exhibition of these works. Still he was hopeful, and through the intercession of influential friends in San Francisco, his work was brought to the attention of the Curatorial Committee of 80 Langton Street, an alternative exhibition space.

Eighty Langton Street, a non-commercial institution, was founded four years ago by the San Francisco Art Dealers Association (from which it is now independent) for the exhibiting of works of art that, for reasons of either form or content, are not shown in galleries and museums. Most often 80 Langton Street, located in the city’s industrial South of Market Street area, and formerly a casket factory, shows conceptual, non-static, non-object and performance works.

While the form of Mapplethorpe’s works is certainly conventional – 16″ x 20″ black-and-white photographs – the content, equally certainly, is not. The members of 80 Langton Street’s volunteer Curatorial Committee, artists, gallery and museum people, men and women (all straight, by the way), put aside their personal, moral proclivities and decided to exhibit the work on the basis of aesthetic criteria: composition, lighting, gradations of tones from black to white, and so forth.

Mapplethorpe’s exhibition, title “Censored” because of his earlier experiences in trying to get the work shown, consisted of 19 images selected by guest curator, San Francisco art-dealer Edward de Celle. It included a self portrait of the artist which appeared on the announcement for the exhibition-now a collector’s item. With a whip’s handle up his ass, he resembles a scorpion.

The toughest photographs in this very tough show were a sequence of four images of progressive mangling of male genitalia, concluding with a bloody orgasm. The device used resembles the stocks (in miniature) often employed by our Puritan forebears for punishing miscreants. It fits around the penis and testicles, however, rather than neck and limbs.

For all their gruesomeness, the images in this sequence are striking in their resemblance to works by the patriarchal American artist, Willem de Kooning, in his distortions of the human figure and expressionistic use of paint. The depersonalization in the images, a separating of the subject mind from his body and of the artist’s “self-distancing” from the subject, was accentuated by the harsh flashbulb light used by Mapplethorpe. (For those who care, the subject, and his lover, whose hands also appear in the series, do “get off” on the process.) In comparison, the other works exhibited appear sedate, even elegant, and sometimes humorous-but only in comparison.

In making such S&M photographs, Mapplethorpe’s purpose is to document human experiences that have until now been either ignored or suppressed. Aficionados of S&M, though a minority in the gay as in the non-gay world, are human. What comes across in Mapplethorpe’s images are the physical strength of the subjects and the tenderness of their helpers in the exploration of the poetry of pain.

Mapplethorpe initially became a photographer, – after having worked in other art media, because he wanted to take “dirty pictures” of himself with a Polaroid camera. He prefers the term “pornographic” to “erotic” to describe his work – but he insists that he makes pornography that is art. No one else, he feels, has worked with the subject matter as he does. “42nd Street just doesn’t go beyond a certain level. I do work that’s worth doing.”

While Mapplethorpe enjoys photographing sex, he enjoys sex itself more. “Sex without the camera is sexier. Sex is the highest art form. It’s the most complicated thing men can be involved in. It has a magic in it comparable to the magic in great art.”

“The point of making art,” Mapplethorpe asserts, “is educating people.” His exhibition at 80 Langton Street may not have been to everyone’s taste, but it was instructive and did increase awareness about what is means to be a human being.

Other Mapplethorpe exhibitions at the Simon Lowinsky Gallery in San Francisco and University art Museum in Berkeley have also revealed the artistic vision of a significant young American photographer– All the works shown are consistent in the photographic beauty of their images.

CENSORED

Robert Mapplethorpe

March 21 through April 1, 1978

Reception: Monday, March 20, 6-8 p.m.

80 Langton Street, San Francisco

(415) 626-5416

Gallery Hours: 1-5 p.m.

Tuesday – Saturday