Tee Corinne: Self Portraiture

Tee Corinne – Self-portraiture in the Lesbian Community & Picturing Cancer in our Lives.

With Tee’s subsequent passing in August of 2006, we decided to bring these photographs together with her stirring lecture on lesbian self-portraiture – a tracing of the vibrant history and different modes of expression – and in a sense surround her with her peers. This exhibition was presented at SomArts Cultural Center in San Francisco in June of 2007 as: “Tee Corinne – Self-portraiture in the Lesbian Community & Picturing Cancer in our Lives.”

SELF-PORTRAITURE IN THE LESBIAN COMMUNITY

(Reconstructed from an essay by Tee A. Corinne)

Curated by Aspen Mays

A Century of Lesbian Self-Portraiture: a slide lecture

In addition to her own investigations of the photographic self-portrait, part of Tee’s legacy was her tireless research and celebration of other lesbian artists. The following are excerpts from a slide lecture Tee presented at the Women’s Caucus for Art 1992.

Any search for lesbian self-portraits is, for a lesbian artist, a search for iconographic precedents, a quest for role models and peers.

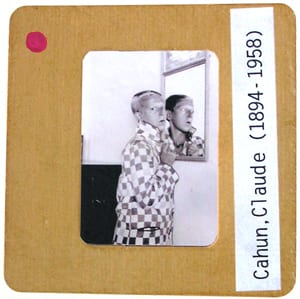

I skimmed the text looking for code words like “never married” or “life-long companion” and was pleasantly surprised to find the word “lesbian.” It was an article about Claude Cahun, born in 1894. I asked myself, as I have before: “Why haven’t I heard of this woman?” Personal reticence? Family interference? Negative social attitudes?

Whatever the reason, I’m grateful to have access to her imagery.

Any search for lesbian self-portraits is, for a lesbian artist, a search for iconographic precedents, a quest for role models and peers.

I skimmed the text looking for code words like “never married” or “life-long companion” and was pleasantly surprised to find the word “lesbian.” It was an article about Claude Cahun, born in 1894. I asked myself, as I have before: “Why haven’t I heard of this woman?” Personal reticence? Family interference? Negative social attitudes?

Whatever the reason, I’m grateful to have access to her imagery.

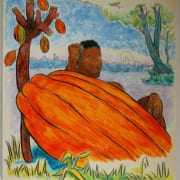

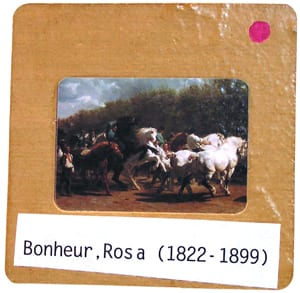

There are other provocative self-portraits by past lesbian artists. If James Saslow is correct, the central androgynous image in Rosa Bonheur’s “The Horse Fair” of 1883 is actually an image of Bonheur (1822-1899) herself.

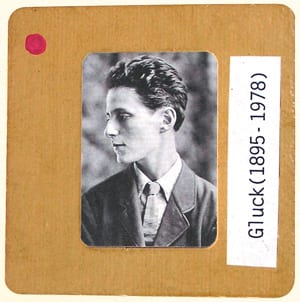

Gluck (b. Hannah Gluckstein, 1896-1978), English, Jewish, was one year younger than Cahun. Gluck’s self-portraits reflect her preferred, masculinized self-image.

There is a broken tradition in the study of lesbian visual arts because of the fear by many lesbian artists, art historians and critics that if their love of woman were known they would lose their chances of success in the larger world.

|

|

|---|---|

| Untitled (Self-portrait) Gluck 1919 |

The Horse Fair Rosa Bonheur 1853 |

|

|

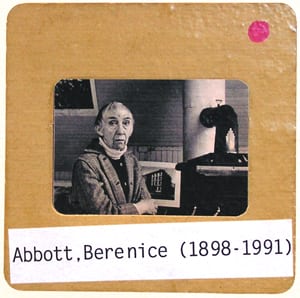

| Untitled (Bernice Abbott at 83) John Loengard 1976 |

Cathy Cade, who has a Ph.D. in Sociology, has concentrated on photos of working women and lesbian mothers with their children.

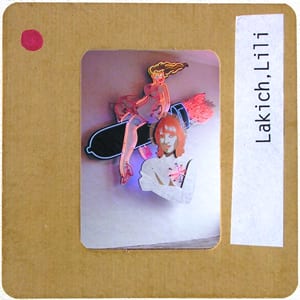

Neon Artist Lili Lakich has been professionally active for almost three decades. In the 1980s, Lakich was published by the pioneering lesbian magazine, “The Ladder.”

Happy (L.A.) Hyder brings her awareness of marginality as a Lebanese American to her imaging.

Deborah Bright, with her playful self-insertation into old movie stills, has claimed a new kind of imaginative lesbian space.

Photographs by Roberta Almerez were first seen in “Between the Lines, An Anthology by Pacific/Asian Lesbians of Santa Cruz, California,’ in 1987.

“Forbidden Subjects, Self-Portraits by Lesbian Artists,” (1992) expanded lesbian visibility. From its cover image by realist painter, Lenore Chinn and others, this thoughtful, graceful volume does more for international lesbian art visibility than a multitude of exhibitions.

Jean Weisinger’s name is often on the credit line of photos of Audre Lorde and Alice Walker. In “Forbidden Subjects” she writes that “Seeing Myself Through Alice Walker’s Eyes” ‘expresses…a new way of seeing myself. A BIRTH.’

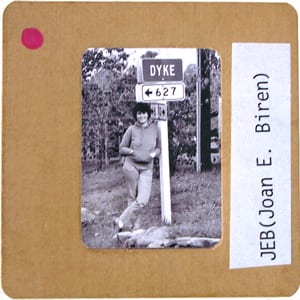

JEB (Joan E. Biren) was one of the earliest out lesbians documenting this wave of U.S. Feminism.