Bernice Bing by Jen Banta

The Painting in the Rafters: Re-Figuring Abstract Expressionist Bernice Bing

by Jennifer Banta, 2009

What is the mystery? The mystery is the work in process. Visually, I sense a great order of things and attempt to transpose this mystery into a picture. I used to look for meaningful order in life, now I am accepting things as IS. That nothing is certain, and in my imagery is ever-changing. We are at an epoch of a brave new world, and my hope is that our views will change about how we see our world, not to stay with the things familiar, but to reach out for the unknown.

– Bernice Bing, Artist Statement for the Triton Museum Exhibition, 10/18/92

My tiny office with the Asian Pacific Islander Cultural Center, perched above the SomArts Gallery, is a site for exchange, community, politics, laughter, and ambitious cultural production. SomArts, one of six city-owned cultural centers, has history in every crevice The ineffable presence of those who came before pervades this space. Stored beneath the rafters above my desk, for example, was a 1980 painting by the first Executive Director of SomArts–painter Bernice Bing. Burney Falls was one of several canvases that she painted of this location in Northern California, sometimes called the eighth wonder of the natural world. (fig. 1)

I was told that Bing’s painting had been haphazardly propped up in the hallway until it was recognized and rescued to higher ground. The fact that Bing’s painting was stored in such a manner would seem to be at worst a high art crime, at best sheer neglect. I could not reconcile this lack of respect, yet it seemed oddly emblematic of the treasure trove that is SomArts, where high and low art comingle.

The specter of invisibility has become the conduit for considering how a desire to create a visual archive of Bernice Bing’s life, art, and legacy has as much to do with excavating and preserving the material of her artwork as with her lived experience. I needed to understand the importance of the spiritual path Bing followed and the meditation practice that gave her focus and confidence as well as her search for her diasporic community in order to begin to navigate this in-between space. By approaching this task experientially, through listening to stories, looking at her paintings, and reading her journals, I too have found myself in the mystery of constant discovery. I am drawn to this state of absence, and I find that presence is returned by how I negotiate this space. I believe that art provides a medium for accessing this space of forgotten stories– making visible the invisible. As if the catalyst for my intent had been far closer than I could have realized, with Burney Falls hanging above my head every day, Bernice Bing’s oeuvre needed to be, in effect, dusted off and brought to light.

What exactly were the conditions that contributed to Bing’s marginalization? It is perhaps all too familiar an occurrence that a lesbian artist of color was filtered out of art history. If I accept this reality as a given, then I must also go beyond this banal fact and tease out the details of her story. There are so many facets of Bing’s identity–all of which beckon to be further explored, including the period of Beat history that contains such fissures and forgotten stories. Bing had access to the art world as an integral player.[1] Her marginalization occurred with the passage of time.

Perhaps the materialistic aspect of preserving Bing’s art is antithetical to the fact that her work was rooted in process and the negotiation of mystery. On the relation between art and Buddhist spirituality, Bing stated, “I haven’t learned to let go of art. The highest form of art is a vehicle, a mantra. I am burdened by the materialistic aspect of producing art.”[2] I am intrigued by the complex and dynamic relations between Bing’s life and work. At present, there is little written about Bernice Bing save for the work begun by Moira Roth and the memorial essay written by Lydia Matthews, both archived on the Queer Cultural Center’s website by Rudy Lemcke. Despite this paucity of textual material, I find myself in the privileged position of being surrounded by people who knew and loved her.

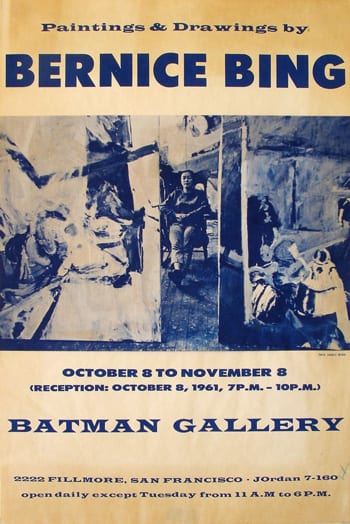

Spontaneous moments arise at SomArts where I find myself in conversation with people who knew Bernice Bing. Bing’s life had a catalyzing effect on a group of people who came together after her death to remember and honor her life, and who remain connected. Lydia Matthews, in the essay she wrote to memorialize Bing after her death, Quantum Bingo, writes, “Hers was a powerfully sustained yet quiet career. This kind of artist can easily fall through historical cracks if we do not diligently keep her memory alive.”[3] Indeed, Bing has now largely fallen through the cracks, though in her lifetime she was quite visible. During the 1950s, Bing was among the first generation of post-war women artists in California, and after her graduation, Bing enjoyed a one-person exhibition at the Batman Gallery, one of several Beat galleries that appeared briefly during the late ’50s and early ’60s in San Francisco. Bing appears in the poster announcing her 1961 show, surrounded by her paintings in her studio above the Spaghetti Factory in North Beach, the seat of Beat activity. Bing received early critical acclaim for her work with a 1963 and 1964 Artforum review by critic James Monte. In many ways, this period marked the beginning of a promising career. However, this level of recognition waned substantially over the ensuing years, often due to her difficulties in surviving financially as an artist, time devoted, at least in part, to administrative duties (such as her role as the first Executive Director of SomArts), and her failing health. (fig. 2)

The art community in the San Francisco Bay area experienced a surge of creative energy after World War II, and the city was the site of interchanges between abstract painters, Beat poets, jazz musicians, the West and East coasts, as well as artistic and spiritual contacts with Asia.[4] This zenith of creativity encompassed a Beat sensibility that included collaboration, collectivity, and many forms of artistic expression. What was it like to come of age artistically during these times? In many ways, this post-war period represented a liminal stage, and Bing was an integral player in this moment.

San Francisco’s Bohemian history is rich and has been lovingly documented in numerous publications, yet these tales are only part of the story. In the Bohemian milieu, the masculine world of the literati and the male subjectivity of Abstract Expressionism dominated. Of course, women were present and not just as wives and stunning guests at parties and openings, but as business partners and artists. Rebecca Solnit has written extensively about Beat painting as concurrent with that of the literati’s activities during this period in the catalog accompanying the Whitney Museum of American Art’s exhibition, Beat Culture and The New America, 1950-1965.[5] She explicates that though the historical focus has always been on the literati’s activities in North Beach, the strong presence of painters and jazz musicians in the Western Addition promoted significant artistic exchange. The two prominent women in this group that Solnit writes about were close friends of Bing’s: Jay De Feo (married to Wally Hendrick) and Joan Brown (married to Manuel Neri).

Romantic alliances that were formed within this bohemian haven were an integral part of the movement and formed a nexus of lovers, partners, and roommates. A woman’s success and visibility as an artist was no doubt heightened by the partnerships she formed with successful men, and in many ways created a conflation of roles previously prescribed to women in bohemia’s history, such as the unsettled distinction between woman as muse and woman as artist. This idea was perhaps most clearly defined within Surrealism by Andre Breton, who attributed the female muse with child-like qualities that he saw as closer to the unconscious than men were.[6] Although De Feo and Brown were talented artists in their own right, I think it is important to question why they are written about and not Bernice Bing, the lesbian artist. Their marriages, as far as history is concerned, ensure that they are remembered by association.

Bernice Bing was born in San Francisco’s Chinatown in 1936. Her mother and aunt worked as hat girls and dancers in Chinatown’s infamous Forbidden City, a Chinese-themed cabaret frequented by military personnel. For Bernice’s mother to choose to step out of the tightly prescribed domestic female roles was to invite a certain degree of ostracism from the community. She did it anyway; it was a job, and the Depression was in full force. Bing’s aunt Lonnie was also drawn by the allure of late nights, glamorous costumes, and people from outside Chinatown;[7] it is unclear whether this was the case for Bing’s mother. However, I like to think that this act became a legacy for Bing who was continually drawn to the avant-garde and spent her life deeply immersed in a variety of different worlds while maintaining separate identities. (fig. 3)

Bing’s mother died when she was a young girl. Though her father, grandmother, and aunt were alive, both she and her younger sister Lolita spent their childhoods shuttled between Caucasian foster homes with only sporadic contact with their Asian relatives and infrequent visits to Chinatown. Bing was not an orphan since she had next of kin, but was orphaned nonetheless from her primary family. In her memories of her childhood, Bing emphasizes the cultural differences she experienced:

“My grandmother represented China, the old country, bringing over her feelings of anger and subservience, but her strength, too. She was a woman who had bound feet, bound at the age of five. I didn’t really know my mother but, of course she was my grandmother’s child . . . my mother had an ambitious life as a young woman but she was never able to fulfill herself completely because she died at the young age of twenty-three. For me there was the difficulty of being an Asian American child going to a basically very middle class white school, and trying to assimilate both of these cultures.”[8]

The early rupture in her life caused by her mother’s death disconnected her from the key sources of cultural transmission. Gone were the superstitions, the stories, the language, and the food that all serve as conduits for transferring her Chinese culture from the elders in her family. Though she was raised in foster homes, she had relatives who exposed her to her Chinese heritage through the occasional visits, and this was enough to spark an interest which she pursued as a young woman through her studies and for the rest of her life.

Her memories of Chinatown (the sights, the smells, the colors, and sounds) were only a memory, not something that was directly cultivated growing up. How does such an influence grow? In the absence of an environment that nurtures a sensibility, is there information in the space of memory that provides an intuitive map to navigate the world?

At that time I knew almost nothing about Eastern art or thought. I was totally naive about my own cultural heritage. I was living in and reacting to parallel worlds–one, the rational, conscious world of the West; the other, the intuitive, unconscious world of the East. This duality caused me to explore the differences and samenesses in art forms.[9]

Is Bing strategically toying with stereotypical notions of East/West dualism here? When she refers to the West as “conscious” and the East as “unconscious,” I am inclined to think this construct refers tacitly to the organizing principal of interconnectedness that is understood as part of a dualistic whole. If I understand that in every cliché there is an element of truth, then it compels me to go beyond the face-value of her statement. It also has to be acknowledged that, given she was born, raised, and educated in the United States, her context, first and foremost, was a hybrid of the experiential, the learned, and the intuitive, given her artistic sensibilities.

Bing’s statement can also be understood as an admission of her own naiveté about her cultural heritage. In fact, Bing later turned to a Japanese mentor, Sabro Hasegawa, who inspired her with a context to begin thinking about her heritage. In her words, “I had no idea what it meant to be an Asian woman and he got me started thinking about that. I was in awe of him.”[10] This reveals a complex process that included all sorts of intercultural knowledge. Bing’s lack of experience and innocence in this regard, along with her hunger for knowledge about her heritage, would have included impressions gleaned from the dominant culture at the time. Clearly, this process was a life-long endeavor of absorbing information and discovering self-truths.

Gifted with a facility for drawing at a young age, art became the means by which she navigated the two worlds in which she lived: the memory of the brief exposure to her Chinese culture in the first years of her life, and the Western context in which she was raised. Nona Mock Wyman, in her memoir about growing up in the same orphanage as Bing, titled Chopstick Childhood In A Town of Silver Spoons: Orphaned at the Ming Quong Home, recalls the nuns who washed Bing’s mouth out with soap as punishment for her smart and feisty tongue.[11] Raised in an orphanage, Bing was not a dutiful Chinese daughter curtailed by the family structure. The story Wyman tells is emblematic of Bing’s angry rebellion and unwillingness to conform. This spirit would follow her throughout her life and find its outlet in her paintings. Early in her student career, Bing was drawn to teachers that could inform her about painting, calligraphy, abstraction and Zen. In other words, her early facility for drawing became the means by which she also was able to access and learn about her heritage.

Bing was also deeply influenced by her studies in Abstraction with Richard Diebenkorn and Nathan Oliviera. In her book, Abstract Expressionism, Other Politics, Anne Gibson points out that Abstract Expressionism (a style whose definition was intimately related to the identity of the artist), while being promulgated as a universal story, has been told as a triumph of the outsider. Abstract Expressionism represented a rebellious movement born of the post-War period in America. This narrative, based on the trials of a privileged group of white, heterosexual bohemians and intellectuals, and celebrated by critics such as Clement Greenberg, reflects the story of Abstract Expressionism as it has been written into the art historical canon.

Artists such as Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning were enamored with the idea of a pure process related to self-discovery through painting. The time of Abstract Expressionism was also the era of New Criticism in which political affiliations were suppressed along with one’s biography. As a result, Gibson contends, Abstract Expressionism emerged as the “work of artists of one gender, one color, and one sexual preference…while critics also insisted that their judgments were made without reference to the artist’s identities.”[12] Abstract Expressionism claimed the mantle of marginality and appropriated aesthetic strategies (such as masking, maternalism, and social invisibility) that paralleled experiences more familiar to blacks, women, gays, and lesbians and was certainly resonant to Asians experiencing bitter and protracted prejudice in San Francisco during this time in American history.[13] In particular, from the turn of the twentieth century, until its repeal in 1943, the Chinese Exclusion Act was a national system formed specifically for regulating Asian immigration, a system that invoked fear and suspicion of Asian Americans in the larger community.[14]

Clement Greenberg and some of the influential critics that followed him all practiced this kind of New Critical/Death of the Author interpretation that actually perpetuated the power and privilege of the individual artist within a space of critical denial. How does one understand this notion of the self? In this context, an understanding must first address the construct that in many ways actively appropriated styles and tropes from other traditions while positioning Abstract Expressionism, in Greenberg’s words, as an “art that lies almost entirely within Western tradition.”[15] Nothing is pure. What is authentic is entirely subjective to the individual and, perhaps, takes a lifetime for that individual to discover.

Bing’s understanding of the East came largely from her own desire to pursue this knowledge as a young woman, namely through her studies with Sabro Haesgawa at the California School of Fine Arts who introduced her to Zen, the writings of Lao Tzu, and Chinese painting. Based on Bing’s own biography, the historical references Bing makes to calligraphy, philosophy, and ancient Chinese Art in her work drew from her experience. Her search represented an excavation of her roots and was a reflection of her unfolding identity. At the same time, it represented a confluence of different styles and cultures.

In 1997, the year before she died, her painting, Burney Falls (1965), was included in Asian Traditions / Modern Expressions: Asian American Artists and Abstraction 1945-1970, a traveling exhibition organized by the Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University. Burney Falls (1965) closely references the one-stroke approach of traditional Chinese ink landscape painting, rendered in washed-out blues, browns, and greens. It is also deeply rooted in the natural scene in Northern California where it takes its name and the California Abstract Expressionism that Bing studied. (fig. 4)

During the period of Abstract Expressionism’s development, a significant number of Asian American artists comprised a largely unnoticed group of abstractionists, according to the exhibition curator, Jeffrey Wechsler. He proposes that this art, “centered in nature and meditative rather than assertive in spirit, has roots in a fundamentally Asian esthetic.”[16] Wechsler further suggests that the signature features of Abstract Expressionism (gestural brushwork, a restricted palette) had time-honored Asian precedents.[17] Wechsler understands Bing’s work in the context of geography/biography and the historical traditions by which her work is influenced. This context is provocative given that Abstract Expressionism, at its advent, was promoted by critics such as Clement Greenberg as a purely American Art form. Wechsler proposes a much more fluid re-framing of this moment based on a confluence of different traditions, coincidences, and influences rather than a spontaneous generation on American soil.

Art Historian Margo Machida asserts that the framing of issues “through an Asian American lens continues to be widely regarded as parochial and self-marginalizing.” At the same time, “there is nothing inherently restrictive, essentialist or balkanizing about concepts like difference and identity.” In fact, essentialism further collapses the scope of inquiry rather than inviting further investigation and imagination.[18] Machida maintains that reproducing Asian American visual art without new means of interpretation and contextualization is problematic. As the world becomes an increasingly hybrid, transnational environment, the issues of meaning and cultural translation have to move beyond the rhetoric of race and ethnicity. In this premise, there is a provocative question concerning intercultural knowledge. If it can be said that the discourse has evolved beyond mere representation as a means to counterweight stereotypes, than it can also be said that anybody’s biography contains complex and disparate elements. Bing’s biography complicates and adds depth to her art because she was actively engaged in an ongoing process of examination. Not everyone elects to do this, and it takes a certain degree of courage to look within in this manner.

In 1958 Bing transferred from the California College of Arts and Crafts, where she had studied advertising, to the California School of Fine Arts to pursue a degree in painting. She earned a BFA with honors and went on to graduate as part of the first MFA class in 1961.[19] Bernice Bing, or Bingo as she was affectionately called since childhood, was part of a Bay Area art scene that included Joan Brown, Bill Wiley, Robert Hudson, Leo Vallidor, and Cornelia Schulz–colleagues in her 1961 MFA class at the California School of Fine Arts.

After her graduation, she enjoyed a one-person exhibition at the Batman Gallery. The Batman Gallery was so-called due to the influence of poet Michael McClure (who, when asked about the origin of the name, quipped, “You know, battling the forces of evil.”) and the “blackness” that was artist Bruce Connor’s creation: black floor, black ceilings, the complete opposite of what you would see in most galleries with their stark white walls.[20] This alternative site for artists and intellectuals was still a decidedly male-authored environment. William Jahrmarkt financed the Batman Gallery, and McClure and Connor were instrumental is its design and concept.[21]

Alfred Frankenstein reviewed Bing’s solo show at the Batman in the San Francisco Chronicle: “Bing . . . has a remarkable gift for fluid line . . . carried to the verge of abstraction in some extremely good small drawings. Her paintings are huge and are most remarkable for the majestic sternness of their blacks and reds…” [22] The artists who inspired Bing (de Kooning, Kline, Motherwell, Still [23] favored monumentally scaled works that stood as reflections of their individual psyches [24]. Bing also favored huge works that were as bold a statement as her male counterparts. It could be surmised that she was able to garner a solo show at the Batman because of the scale of her works, at a time when a one-woman show was rare. Bing’s work was informed by this confident masculine energy, while at the same time she was unassuming. According to Bing, the Batman show was “surprising” to her contemporaries since she did not make a lot of noise at school.[25]

In the poster announcing the 1961 show, there is a degree of brazen, almost defiant, authorship in this tableau, as she sits in a rocking chair, looking boldly at her audience. Bing creates a diptych with the arrangement of the paintings in the poster that moves us from one chapter of art history to the next. She places her physical body within the field, in a triangulation of art history. To her right, her 1960 painting of Las Meninas, based on the famous 1656 painting by Diego Velázquez, the painter of King Phillip IV, represents Western figurative painting and to her left, is an unidentified abstract study. The bold horizontal lines on the left connect the scenes and suggest a continuation. As we look at her and her paintings, she also looks at us; we have entered the sanctified space of her studio. In this moment, we have happened upon Bing, who seems to radiate a quiet sovereignty. (fig.5)

It was typical of art education at the time to have students recreate paintings by the masters of art history, just as they had done for hundreds of years. Bing painted Las Meninas in 1960 when she was still at the California School of Fine Arts. Velázquez’s Las Meninas shows a large room in the Madrid palace of King Philip IV of Spain, and presents several figures, most identifiable from the Spanish court. Just behind the figures, Velázquez portrays himself working at a large canvas while looking outwards at the viewer.[26] In Bing’s Las Meninas, the focal point of the scene is arranged around the Infanta Margarita. The depiction of the painter in the left of the canvas is abstracted to the background, though the canvas he is working on predominately frames the scene. The presence of the Infanta highlights the female looking out of the painting at the viewer. By recreating this painting, Bing is also aligning herself with the master who painted the scene. (fig.6)

The scene staged by Bing in the poster for her exhibit at the Batman Gallery mimics, in certain ways, Velázquez’s famous painting. Velázquez placed himself to the side of the painting on which he is working, and, significantly, Bing is framed by several large paintings in her own studio. Both artists identify as painters and associate themselves within the represented scene. Though Bing is not actively working on her paintings in the same way as Velázquez, the scene is staged at the site of her production, within her studio, and her paintings serve as her entourage. Her gaze, like Velázquez, signals an awareness of the viewer.

Michel Foucault’s study of Velázquez’s Las Meninas focused on the artwork itself as though it were before him, describing in minute detail what he saw. [27] Foucault conceptualizes the significance of this painting as a “self-reflexive meditation on the nature of representation” which signals a paradigmatic shift in Western culture regarding representation.[28] Foucault writes, “We are observing ourselves being observed by the painter, and made visible to his eyes by the same light that enables us to see him.”[29] Through Foucault’s act of observing and describing the painting, he reveals a reciprocity of looking that complicates the relationship between those who are represented and those who look. In effect, there is a degree of uncertainty in visual representation. Bing suggests a shift in the field of abstraction that is dependent on the viewer’s interpretation. Here Bing shows in visual terms the thesis that Foucault later elucidates with language. Bing’s choice is oddly prescient as Foucault’s study of Las Meninas would not be writtern for another six years.

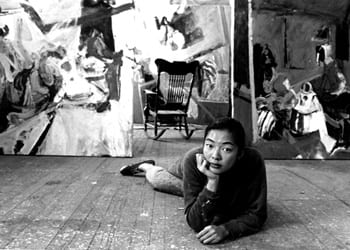

The photographer Charles Snyder captured Bing during the late fifties in several iconic shots in her studio, including the one used for the Batman Gallery poster. In a second photograph, the scene is similarly framed as the one for the poster, except that here Bing is in the foreground, lying down on the floor, her sweatshirt and clam-diggers spattered with paint, her chin resting in her hand. Her gaze fully engages the viewer and the photographer. In the background, the rocking chair is framed by the two paintings but has been turned to face the other way. The informal air to this scene reinforces that the studio is where she is most at home. (fig.7)

In another image by photographer Grover Sales, Bing is captured as if in contemplation of her painting that fills the background of the frame. (fig.8) Here, in the midst of her reverie, she looks out at the viewer who has entered her space. Bing is wearing a white oxford with the sleeves rolled up, her hair pulled loosely back, and her trademark red lips captured in black and white. Her hand holds a lit cigarette; the tendrils of smoke become part of the field of abstraction in her painting. There is something seductively voyeuristic about these shots and I can’t help but describe her presence in these glamorous and feminine terms. I would venture to assert that, here, Bing assumes the “the mask of femininity” as she poses within her studio. According to the analysis of Joan Rivière, in her essay, “Womanliness as Masquerade,” “womanliness therefore could be assumed and worn as a mask, both to hide the possession of masculinity [read power and authority] and to revert the reprisals expected if [the women] was found to possess it.”[30] There is a symbiotic relationship between Bing and the paint that reveals an intimate and carefully crafted look at the artist.

The Sales photograph presents one version of Bing’s “self,” embodying both her authority as an artist and her feminine presence. The similarities between the photograph of Bing in the white oxford and the photo that appears on the Batman Gallery poster are as striking as the marked differences, and I can only surmise why one and not the other, in the end, was chosen for the poster. Ultimately, by reframing and developing the shadow presence of the Batman Gallery and by extension, the times around Abstract Expressionism and the Beat movement in San Francisco, the whole picture comes into focus. The Batman Gallery poster is a piece of ephemera that function as one of the few remaining testimonials to this place and time.

Reading the poster provides clues to the context of history, gender, and Bing’s concurrent quest for identity that make clear the need to expand the art historical canon to acknowledge the key role of this visionary painter. The poster demonstrates that Bing was present and that she was an integral player in Beat History. At the tail end of the fifties, a time dominated by the masculine presence in the arts, Bing chose to identify in bold and unmistakable terms that she was a painter, while positioning herself squarely within the trajectory of art history.

Burney Falls was returned to the Bing estate in July 2009- an end of an era and a reminder that there is still much to do… this is dedicated to the memory and spirit of Bernice Bing and Jack Davis- may we never forget.

[1] In 1960, Bing accompanies Joan Brown a close friend at this time, to New York, for Brown’s first one-person show at the Staempfli Gallery. Meets Duchamp at a party. “That was my most thrilling experience in New York.” Moira Roth, “A Narrative Chronology”, in Moira Roth & Diane Tani, eds. Bernice Bing, (Berkeley, CA: Visibility Press, 1991), 22-23.

[2]Bernice Bing , Video Interview with Moira Roth, 1989

[3] Lydia Matthews, “Quantum Bingo,” (San Francisco: SomArts Gallery, Retrospective Exhibition, 1999).

[4] Susan Landauer, The San Francisco School of Abstract Expressionism (Berkeley, CA: University of CA Press, 1996), 5-6.

[5] Rebecca Solnit, “Heretical Constellations: Notes on California, 1946-1961,” Beat Culture and The New America, 1950-1965, (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1995), 69.

[6] Briony Fer, David Batchelor and Paul Wood, Realism, Rationalism, Surrealism: Art Between the Wars, (London: Open University, 1993), 237.

[7] Lenore Chinn, in conversation with the author, (July 3, 2008).

[8] Moira Roth, “A Narrative Chronology”, in Moira Roth & Diane Tani, eds. Bernice Bing, (Berkeley, CA: Visibility Press, 1991), 22-23.

[9] Asian American Women Artists Association, Of Our Own Voice, (Berkeley, CA: AAWAA, 1998), 13

[10] Moira Roth, “A Narrative Chronology”, in Moira Roth & Diane Tani, eds. Bernice

Bing, (Berkeley, CA: Visibility Press, 1991). 22-23.

[11] Nona Mock Wyman, Chopstick Childhood In A Town of Silver Spoons: Orphaned at the Ming Quong Home (Walnut Creek, CA: MQ Press, 1999),

[12] Ann Eden Gibson, Abstract Expressionism: Other Politics (Connecticut: Yale University Press, 1999), 59.

[13] Ann Eden Gibson, Abstract Expressionism: Other Politics (Connecticut: Yale University Press, 1999).

[14] Life on Angel Island, Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation, 200-2008 http://www.aiisf.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=58&Itemid=71, (accessed on April 8, 2009).

[15] Ellen G. Landau, ed. Reading Abstract Expressionism: Context and Critique, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005), 207.

[16] Jeffery Wechsler, ed. Asian Traditions/Modern Expression: Asian American Artists and Abstraction, 1940-1970, The Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum. (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1997.)

[17] ibid.

[18] Elaine H Kim, Margo Machida, and Sharon Mizota, eds. Fresh Talk, Daring Gazes: Conversations on Asian American Art, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003). xi-xiii.

[19] Edited by Moira Roth & Diane Tani, Bernice Bing, (Berkeley, CA: Visibility Press, 1991).

[20] Jack Foley, “O her blackness sparkles!” in The Beat Generation: Galleries and Beyond, (Davis, CA: John Natsoulas Press. 1996),163.

[21] Jack Foley, 164.

[22] Alfred Frankenstein as quoted in Moira Roth, “A Narrative Chronology” in Bernice Bing. 26.

[23] Bernice Bing, Artist’s Statement. Completing the Circle, (San Francisco: Southern Exposure Gallery, 1990).

[24] Paul Stella. “Abstract Expressionism”. In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/abex/hd_abex.htm (accessed September 5, 2008).

[25] Ibid.

[26] Madlyn Millner Kahr. “Velazquez and Las Meninas”. The Art Bulletin, Vol.57, No. 2, June 1975. 225.

[27] Michel Foucault, “Las Meninas,” The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (London: Routledge. 2002), 3-18.

[28] Yvette Greslé, “Foucault’s Las Meninas and art-historical methods,” Journal of Literary Studies, Volume 22, Issue 3 & 4 (London, England: Routledge Press, December 2006): 211-228.

[29] Michel Foucault, “Las Meninas,”5.

[30] Joan Riviere, “Womanliness as Masquerade,” first published in International Journal of Psychoanalysis 9 (1929): 303-313; reprinted in The Inner World of Joan Riviere: Collected Papers, 1920-1958 (London: Karnac Books, 1991), 90-101.