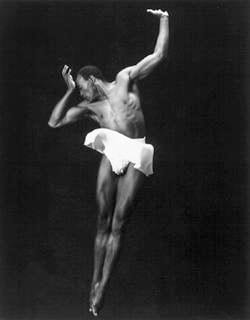

Bill T. Jones

A Louder Public Voice

September 23, 2001

By BILL T. JONES

My company was to have performed at Evening Stars Onstage on the temporary stage set between the Twin Towers the evening after last week’s catastrophe. In thinking about the future of dance, I think about my dancers and dancers in general. I think highly of dancers — not always the culture of contemporary dance, but the armies of individuals engaged in the body-punishing daily ritual of training, rehearsing, traveling and performing. These efforts are often unknown by the mass public and as a result are undervalued in the economic marketplace. I think of the choreographers as well, the architects of time and space who deploy these dancers. Much of the last 20 years or so have witnessed this group of creators searching for a way through an impasse of cultural irrelevance, embroiled as always in a particularly 20th-century preoccupation with loss of identity, loss of conscience and then disease. “The world has changed!,” we choreographers have been told along with everyone else. So it has. How will our work change? Trial and error, reaction and experimentation have defined art even before it declared itself modern. Just as what is deepest in life evades analysis, so it is with any artist’s process. But if we look back not so long ago to another numbing, paralyzing crisis that confronted and continues to confront the dance community — AIDS — we may get some insight. We can expect to see works that plunder history — iconographies of style, personality, fashion — giving all an ironic spin with the intention of expressing our present anxiety and dislocation. Works with a public voice will sound even louder in certain quarters recently vacated by the cool, aloof gestures of modernism. More literary or theatrical in nature, some will “name names,” decry and demand to know what is really happening and who is responsible. These works act as a service of social change that will exploit the potential of movement to communicate and manipulate viscerally. But they will also appropriate with great verve and sophistication mass culture, mass media and the new technology. Just as luxury and expedience as represented by a jetliner were transformed into a weapon of mass destruction, technology will become an even more essential means to critique itself in our changed world. Virtuosity, athletic prowess and the glamour they radiate will find a golden age in the new era. Just as in the midst of a dance world confronted with mysterious debilitating disease, the new era defined by the ever more present reality of decomposing human flesh clutched by twisted metal and rubble will reveal something essential to the dance world’s ethos — to dance strongly, with energy and emotion, is to rebel. “We dance or we die!” has been a battle cry. Are we at war? We shall see. A college professor once told us, “No great art is ever created during battle.” I would say, however, that at such times people do pray and make exquisitely subtle delineations between action and inaction, good and evil. We can expect intense quiet works as intimate as prayer, and others that in their invention and formal arguments will read like fine philosophical discourse. Though artists are justifiably profiled as alienated, unengaged and suspicious of “reality,” few would deny that events of Sept. 11 were but an overture, a beginning. All of the above approaches and strategies will be proposed and executed among further attacks/counterattacks, acts of heroism and its opposite, births, deaths and the thirst for “normal life.” But please, look closely at what will be produced! Some of it will be important. Few other mediums besides dance will offer us such a raw, noncommercial opportunity to witness live bodies negotiate the tyranny of the present and its minefield of unforeseen events.

Bill T. Jones is co-founder and artistic director of the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company.

BIOGRAPHY

Born: February 15, 1952

Occupation: dancer, choreographer

Bill Jones was born and raised in rural Steuben County in upstate New York. He began his dance training as a student at the State University of New York at Binghamton where, as a theater major on an athletic scholarship, he enrolled in dance classes with Percival Borde.

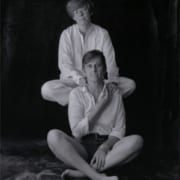

After living briefly in Amsterdam, Jones returned to SUNY in 1973 and joined with Lois Welk in forming the American Dance Asylum. Two years earlier, Jones met his long-time partner and companion Arnie Zane. The two choreographed and performed innovative solos and duos in the 1970s, often employing openly gay choreography. In 1982 they founded Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane and Company, which provided a vehicle for the development of their choreography. Their works increasingly took on evening-length dimensions.

Jones, a tall, powerful dancer, was an outstanding soloist who often mixed video, text, and autobiographical material with his choreography, as he did in “Blauvelt Mountain” (1980) and “Valley Cottage” (1981), part of the trilogy that began with “Monkey Run Road” (1979). Jones and Zane gained recognition as “new wave” or “post modern” choreographers whose large-scale, abstract collaborations, such as “Secret Pastures, Freedom of Information,” and “Social Intercourse,” were visually and spatially altered by contemporary sets, costumes, and body paintings. They danced in costumes by clothing designer Willi Smith and had sets created by pop artist Keith Haring. These collaborative works were performed in prestigious venues such as the Brooklyn Academy of Music and New York’s City Center theater.

In 1983, Jones was commissioned to create the fast-paced, all-male “Fever Swamp” for the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, followed by “How to Walk an Elephant,” in 1985. After Zane’s death in 1988 from AIDS, Jones continued to choreograph and perform. His works expanded to the field of opera and musical theater. He choreographed British composer Sir Michael Tippett’s “New Year” (1990), choreographed and directed Leroy Jenkins’ “Mother of Three Sons” (1991) at the New York City Opera, and directed Kurt Weill’s “Lost in the Stars” in 1992. Jones’ work has been commissioned by companies throughout the U.S. and Europe. In 1986 Jones and Zane received a Bessie Award, and in 1991 Jones was recognized as an “innovative master” with the Dorothy B. Chandler Performing Arts Award. In June of 1994, Jones was awarded a MacArthur fellowship.

— Julinda Lewis-Ferguson