David Wojnarowicz

David Wojnarowicz

by Felix Guattari

Translation from: Rethinking Marxism,

vol 3 #1, Spring 1990

(no original source nor translator given)

David Wojnarowicz’s creative work stems from his whole life and it is from there that it has acquired such an amazing power. It could even be said that it is through his plastic work and literary texts that he has turned himself into what he is today. The authenticity of his work on the imaginary plane is quite exceptional. His “method” consists in using his fantasies and above all his dreams, which he tape-records or writes down systematically in order to forge himself a language and a cartography enabling him at all times to reconstruct his own existence. It is from here that the extraordinary vigor of his work lies. David Wojnarowicz’s intention is explicitly ideological: his aim is to affect the world at large; he attempts to create imaginary weapons to resist established powers.

To better understand how he connects his singular fantasies to a historical scheme, listen to his comments on his major themes, from the steam engine to the gear wheel: “History has been written and preserved by and for a particular class of people so in my work I want to rewrite or give new meaning to the histories that exist in textbooks using present day experience as a departure. For example, in a painting about the American West, I focus on the steam engine; the train that carried white culture through the land inhabited by the Indians. Obviously, judging by the current state of Indian affairs, there was intense exploitation and eradication by white people of anything or anyone that resisted their ‘cultural’ expansion. Given that I wasn’t born at that time, I can only speak of these elements in terms that exist today – I gather them by traveling, or from written works, images in popular culture, dreams and other symbols that will help me construct a discourse about this reality rejected or hidden by the white culture.

“Using gears or machines as symbols is important to me because in the early part of the century the Futurists thought that the machine was God. They placed all their hopes and the hope of civilization on the machine. They thought the machine would liberate people from the slavery of unnecessary labor and leave them free to truly live their lives.

“Take a walk along any river in any country and you can see that the machine is almost defunct; God is rusting away leaving a fragile shell – factories – like the shell of an insect that has metamorphosed into an entirely different creature and flown away. So now if we take the Futurists’ idea of God and make it current I guess God has metamorphosed into the microchip of the computer. So, for me, the image of the gear or the defunct machine is the image of what history means reached through the compression of time. Scientists have discovered that if the head of a moth is cut off it can still continue to lay its eggs; somehow I don’t think civilization is all that different; we are fossilized before we can even make further gestures; society is almost dead and yet it continues reproducing its madness as if there were a real future at the end of its collective gestures. Until the rude shock becomes magnified enough to wake us from this sleep we will continue to have more tiresome dreams…”

What is important is that, through the concatenation of semiotic links he forges, he manages to produce a singular message that allows us to perceive an enunciation in process; a singular vocation can thus be transferred on another plane. The image is not only meant to exhibit passively significant forms, but to trigger an existential movement, if not of revolt, at least of existential creativity. When everything seems to be said and repeated at this point in Art History, something emerges from David Wojnarowicz’s chaos which confronts us with our responsibility to intervene in the movement of the world.

This painter-writer is unique in the sense that he fully subordinates his creative process to the daily disclosures in his life.Thus, he concretely reinstates a principle of singularization in a universe that has too much of a tendency to give in to universalist comfort. This singularization today is all the more dramatic that David Wojnarowicz has the increased possibility of an encounter with death. He knows he has the Aids virus in his body and he integrates this sequence of his life into what may be the ultimate phase of his Aids virus; he reinvents on the way the inspiration of the great ‘60s movements.

His revolt against death and the deadly passivity with which society deals with this phenomenon gives a deeply emotional character to his life work, which literally transcends the style of passivity and abandon of the entropic slope of fate which characterizes this present period.

Paris 1989

David Wojnarowicz Reading

AIDS Community Television

from a benefit fund-raiser for Needle Exchange

David Wojnarowicz (1954-1992) read several works from his writings at the Drawing Center (New York City 1992) as a benefit for Needle Exchange shortly before he died.

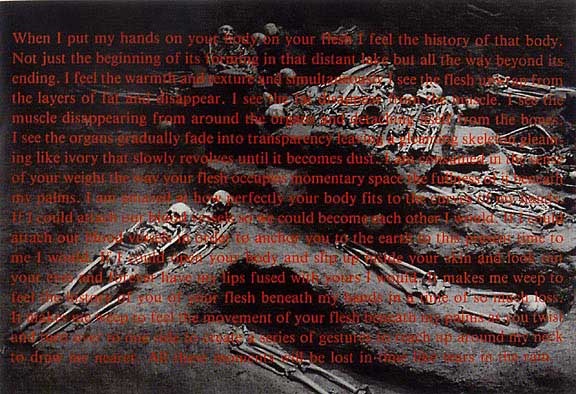

“’If I had a dollar to spend for healthcare I’d rather spend it on a baby or innocent person with some defect or illness not of their own responsibility; not some person with AIDS…’ says the healthcare official on national television and this is in the middle of an hour long video of people dying on camera because they can’t afford the limited drugs available that might extend their lives__ and I can’t even remember what his official looked like because I reached in through the T.V. screen and ripped his face in half__ and I was diagnosed with AIDS recently and this was after the last few years of losing count of the friends and neighbors who have been dying slow and vicious and unnecessary deaths because fags and dykes and junkies are expendable in this country __’If you want to stop AIDS shoot the queers…’ says the governor of texas on the radio and his press secretary later claims that the governor was only joking and didn’t know the microphone was turned on and besides they didn’t think it would hurt his chances for re-election anyways __ and I wake up every morning in this killing machine called america and I’m carrying this rage like a blood filled egg and there’s a thin line between the inside and the outside a thin line between thought and action and that line is simply made up of blood and muscle and bone and I’m waking up more and more from daydreams of tipping amazonian blowdarts in ‘infected blood’ and spitting them at the exposed necklines of certain politicians or government healthcare officials or those thinly disguised walking swastika’s that wear religious garments over their murerous intentions or those rabid strangers parading against AIDS clinics in the nightly news suburbs __ there’s a thin line a very thin line between the inside and the outside and I’ve been looking all my life at the signs surrounding us in the media or on peoples lips; the religious types outside st. patricks cathedral shouting to men and women in the gay parade: “You won’t be here next year—you’ll get AIDS and die ha ha’__ and the areas of the u.s.a. where it is possible to murder a man and when brought to trial one only has to say that the victim was a queer and that he tried to touch you and the courts will set you free__ and the difficulties that a bunch of republican senators have in albany with supporting an anti-violence bill that includes ‘sexual orientation’ as a category of crime victims __there’s a thin line a very thin line and as each T-cell disappears from my body it’s replaced by ten pounds of pressure ten pounds of rage and I focus that rage into non-violent resistance but that focus is starting to slip my hands are beginning to move independent of self-restraint and the egg is starting to crack __ america seems to understand and accept murder as a self defense against those who would murder other people and its been murder on a daily basis for eight count them eight [nine, ten…] long years and we’re expected to quietly and politely make house in this windstorm of murder__ but I say there’s certain politicians that had better increase their security forces and there’s religious leaders and heathcare officials that had better get bigger dogs and higher fences and more complex security alarms for their homes and queer-bashers better start doing their work from inside howitzer tanks because the thin line between the inside and the outside is beginning to erode and at the moment I’m a thirty seven foot tall one thousand one hundred and seventy-two pound man inside this six foot frame and all I can feel is the pressure all I can feel is the pressure and the need for release.”

Partial Bibliography:

Close to the Knives

A Memoir of Disintegration

by David Wojnarowicz

Vintage Books

Random House, Inc

Memories That Smell Like Gasoline by David Wojnorowicz Artspace Books (San Francisco)

David Wojnarowicz,

Brush Fires in the

Social Landscape

Aperture #137

Fall 1994

Seven Miles a Second

comic by

David Wojnarowicz & James Romberger

Vertgo Verite

David Wojnarowicz,

Tongues of Flame

edited by Barry Blinderman University Galleries Illinois State University Normal, Illinois Distributed Art Publishers (New York, New York)

David Wojnarowicz: The Last Rimbaud

by Donald Kuspit

1988

There’s no question about it: David Wojnarowicz had a hard life. It was a kind of loss leader for his art, which reads like a surreal case history documenting it. Wojnarowicz’s artistic career seriously began with Arthur Rimbaud in New York (1978-1979), a series of twenty-four black-and-white gelatin silver prints in which a friend, wearing a mask of Rimbaud, was photographed in a variety of New York settings, all more or less sordid and “underground.” Wojnarowicz’s identification with Rimbaud is clear, and there is a startling resemblance between their lives, and even their art.

Wojnarowicz was born in 1954, exactly a century after Rimbaud, and died in 1992, living one year longer than Rimbaud, who died in 1891. Both were the products of broken homes and abusive parents; both ran away from provincial homes to the big city; both traveled widely; both were gay. Both needed a loving relationship with an idealized father figure and artistic mentor to stimulate and support their own art—Paul Verlaine in the case of Rimbaud, the photographer Peter Hujar in Wojnarowicz’s case—and both were violent personal- ties—Rimbaud eventually shot Verlaine, and death and destruction run rampant in Wojnarowicz’s imagery, most famously in Untitled (Falling Buffalo), 1988- 1989. (In one film, bodies are mutilated and torn apart.) Both had a certain arrogance, evident in Wojnarowicz’s videotaped “performances” as a gay activist. Rimbaud was rejected by the Parisian literati as an arrogant, boorish drunk. At one time or another both lived beyond the social pale, Wojnarowicz as a child prostitute, Rimbaud as a gunrunner. The criminal or outlaw experience gave them pleasure—their art in fact is a kind of homage to the pleasure principle, celebrated as illicit—as Wojnarowicz’s writings, intense and eloquent as Rimbaud’s, indicate. They felt they could get away with being exceptions to the rules everyone else must follow and they paid a human price for it, whatever the artistic compensations. Both died horrible deaths, Rimbaud after having his cancerous right leg amputated—he apparently suffered from syphilis—and Wojnarowicz from AIDS-related illness.

Perhaps most crucially, Wojnarowicz’s imagery pursues the same hallucinatory effect as Rimbaud’s poetry—both attempt to break the mold of artistic stereotypes by suggesting a complete derangement of the senses, as Rimbaud called it—and, like Rimbaud, he tried to transform his suffering into seerdom. That they both failed is revealed in lives that were a prolonged “season in hell.” For both, art became a way of life when no other avenue worked, or seemed possible, because each chose to be an outsider, or had become one by virtue of an unhappy experience of life. However hard they tried to escape from their lives and feelings by transmuting them into art—to turn the sordid raw material of their life into sublime art—they could not do so completely: their images attained a certain vigorous purity but continued to vent suffering and dissatisfaction. Their art did not save them; it permitted them to cope, temporarily. Rimbaud abandoned art when it could no longer help him, and in a sense Wojnarowicz abandoned art by using it to make political statements that blamed the world for his troubles and stopped his development. Indeed, he may have turned to politics because he had nothing more to say about his life. The ruins of their lives washed up on the shores of art, to our benefit, but not clearly to theirs.

But the resemblance eventually breaks down: Rimbaud was an avant-garde innovator, Wojnarowicz an avant-garde decadent. Both were brilliant, but Wojnarowicz ended—brought to an ambiguous populist conclusion—what Rimbaud began: the idea of the artist as an experimental visionary. Wojnarowicz brought down to earth what for Rimbaud was a mystical way of ascending to psychic heaven. Wojnarowicz standardizes and stereotypes Rimbaud’s unusual techniques and puts Rimbaud’s surreal expressionist aesthetics to anti-aesthetic use. He, in effect, makes exoteric, naturalizes, what was once an esoteric art with an esoteric purpose. In short, he conventionalizes what was once unconventional, and does so with a casual ease that betrays its difficulty. Surrealism is vernacularized in the juxtaposition—however momentarily startling the incongruity—of monkey, money, and tornadoes in Fear of Evolution (1988-1989), and expressionism is vernacularized in the untitled series of sculptured heads made in 1984. In both, collage—Wojnarowicz’s major technique—is routine, however lively, mechanical, however novel its content.

The visionary impulse was intact in Wojnarowicz, but his experiments—and he was relentlessly experimental, as his restless movement between painting, sculpture, printmaking, music, film, video, and numerous collaborations indicate—are not as ingenious and radical as those of Rimbaud. They are more clever than subtle, more blatant than intimate. Wojnarowicz lacks the emotional breadth, complexity, and depth of Rimbaud, tending instead to harp on one emotional note—usually rage, as he acknowledges. This is partly because of his populism—evident in his use of collective imagery, comic-strip style, and such social materials as supermarket posters as points of departure—and partly because he wants to make a political point, to put his firsthand experience to social use, which requires that one write one’s ideas large and simplify them. Mass consumption always involves reduction to a common denominator, and Wojnarowicz was torn between the wish to make high art and to influence the indifferent masses. Moreover, if his political imagery did not incorporate his personal narrative, which involved self-mythologizing, his activism would have lost its cutting edge and poignancy.

Having said all this, Wojnarowicz remains a major figure and symbol, largely because of the existential fundamentalism evident particularly in his death-inspired photographs. I am not thinking of the famous masochistic image of him with his lips sewn shut that appeared in the video Silence=Death (1990), nor of the frequently sadistic character of his imagery, in which hostility often climaxes in murder. Rather, I am celebrating his sophisticated, nuanced use of black and white, suggesting the closeness and even mutuality of death and life, in his Ant Series and Sex Series (1988-1989) and Dust Track I and II (1990). Black and white intertwine the way life and death do; Wojnarowicz’s demonstration of this is his true visionary achievement. Prosaic images become sheer poetry—the stuff of life is at last transformed into art that transcends it—art that is death defying even as its entire atmosphere is funereal. As has been said, there is nothing like death to concentrate the mind. And there is nothing like death to bring an art to ripeness.

Hujar died from AIDS in 1988, and Wojnarowicz, discovering that he was HIV positive, realized that he also would also probably die soon. In his last works he faces his death: social critique and homosexual explicitness are embedded in brooding on death. No doubt his social engagement—inseparable from his self-acceptance—was an attempt to be adult, but he was never more adult than when he dealt with death. It was then that he finally came to terms with his lot in life. There is a subliminal solemnity and intensely mournful quality to Wojnarowicz’s last works that is more heroic than their in-your-face aggression. In them he struggled to integrate his death and life instincts to achieve and maintain a sense of ego. He succeeds: we admire the strength of ego that allows him to face his own death and life. He was not, in the end, the vulnerable frog with whom he identified in some images.

Both Rimbaud and Wojnarowicz died midway through life, at the age when Dante became depressed enough to begin his voyage to heaven—to take salvation seriously. In contrast, they never left hell, but they were able to endure it with dignity. Perhaps there was even something more to Wojnarowicz’s art—something that made it even more authentically existential than Rimbaud’s. If, as Milton said, “the Mind…can make a Heaven of Hell, a Hell of Heaven,” then Wojnarowicz, while not able to make the adolescent hell of his mind into the consummate artistic heaven Rimbaud did, he nonetheless used art to arrive in purgatory. Perhaps he was able to do so because he continued to make art to the bitter end of his life—it was a kind of lifeline to which he desperately held—while Rimbaud abandoned art early in life, suggesting it was an adolescent trifle. To reach purgatory is certainly a step beyond hell and the next best thing to heaven, and brought Wojnarowicz closer to salvation than Rimbaud. The lesson of Wojnarowicz is that if one persists in pushing the Sisyphean wheel of art uphill—it always falls back, and one has to start pushing again—one may not only get further in life, but in the afterlife.

Donald Kuspit is a professor of art history and philosophy at SUNY at Stonybrook, and A.D. White professor-at-large at Cornell University.

IDOL WORSHIP:

TALKING WITH DAVID WOJNAROWICZ

(August 1991)

By Owen Keehnen

When I interviewed the amazing David Wojnarowicz in August 1991 it was a very clear case of hero worship. I was in awe of the raw brilliance of this man. It blazed and crackled in every sector of his work — his photos, his film and collage work, his writing… It was how the man lived his life. At the time I was a fledging activist and had just finished reading the explosive and brilliant collection of essays Close To The Knives (Vintage Books) that in my opinion still ranks today as one of the finest and most important piece of writing to emerge from the epidemic.

This interview took place via telephone — me in my stifling Chicago apartment and Wojnarowicz’s in his stifling NYC apartment. I was so struck by the power of Close to the Knives that I mustered my courage and called out the blue asking him for an interview. He had someone over at the time and so he somewhat reluctantly set up a time an hour or so later. Initially during the interview he was guarded and suspicious of me as a journalist and as one who might possibly misrepresent his work and ideas…or even as a possible stalker/fanatic. However, I think what eventually won his confidence in me was the obvious puppy dog enthusiasm I had for his work. Listening to the full recording of our conversation I can almost hear him thinking, this person is not a threat! It is the kind of interview I look back upon and am grateful for the opportunity, but it’s also the kind I read through and think “I wish I would have had a bit more of a cool journalist head about me”. But as I said it was a very clear case of hero worship.

He was an amazing man and an incredible artist. In 1992, only a few months after this interview took place that incredible and dynamic voice was silenced and David Wojnarowicz was dead of complications from AIDS.

Close to the Knives is so excellent and important. I’ve been recommending it to everyone.

It’s odd. I think I’ve gotten 2 or 3 reviews. It’s been pretty quiet on one level, but apparently the book is doing well so it must just be by word of mouth.

Do you sense a conspiracy or push to silence the book. Well, I agree with your stance that Close to The Knives is outside a formula. I’d call it surreal social criticism — like Genet meets Larry Kramer.

The few reviews I’ve read of it have been interesting. It’s like people generally like the book, but can’t understand why.

What was your intention?

My intention has been since I was in my early 20s to write a book about what it was like to live in this country. And it’s a fairly dark book of what I’d experienced up to that point. The issues of privacy and what should remain private are a total joke to me especially in the light of things like the epidemic. The fact is that it’s still exploding mainly because of these insane notions of privacy and the body. There is so much irony in how information is disseminated. We can look at Ronald Reagan’s asshole on TV and in newspapers and yet we can’t discuss health issues pertaining to our bodies. I wanted to write a book to show where people, specifically myself, can get pushed living in this society. It was also a record of things I’ve carried in my head all my life. I wanted to put it down on paper because I’m feeling mortality. I wanted a record of what I cared about, what I was attracted to, what I did in terms of self-destruction, all that stuff.

It’s there. It’s powerful in its anger and immediacy and voice. And it’s visually stimulating at the same time. Your anger is incredibly beautiful.

I don’t see anything wrong with anger. I think it’s a healthy and transitory emotion. It leads you to other things or to action or whatever. People think the only reason why I write like this is because I have AIDS. I’ve had to deal with that the past year or two. People are frightened by any display of anger or writing that deals with anger. This whole nation is so full of denial that it makes people uncomfortable and they can’t deal with that.

What’s your view of the NEA battles?

I have very little respect for the way they’ve handled any of this stuff. The last thing I saw (John) Frohmeyer (NEA director) trying to handle was the ‘Poison’ controversy and he’s getting a little better but I still wouldn’t trust him as far as I could throw him. My experience of what I went through is just sickening. My sympathies aren’t great with the NEA. They haven’t really done shit in terms of getting beyond certain clique mentalities.

I think you state it pretty clearly when you talk about legitimate art as basically the perpetuation of straight white male fantasies.

The right wing and the fundamentalists have jumped into the fray over the past couple of years — (Don) Wildmon (of the American Family Association), (Pat) Robertson, people like that. It’s just a huge moneymaking gambit. A British journalist in the last year filmed Wildmon’s compound and he has seven volunteers who just empty checks out of envelopes all day. Last year he claimed to have made over five million dollars in $10 and $15 dollar donations. It’s a huge racket. They have an effect on art and television and they’re not far from evil. It all boils down to money and notions of power.

“When I was told I’d contracted this virus it didn’t take me long to realize I’d contracted a diseased society as well”. That statement captures so much the ongoing battle occurring in this country.

To have grown up in a time when there were still electro-shock treatments for homosexuality and it was still considered a mental disorder…to be labeled mentally defective by my desire by a country I feel is borderline insane is idiotic. Every direction you turn, in terms of social politics or social concerns, I just can’t believe this country can get any more sick and yet — for example during The Gulf War we’re constantly fed these images of a homogenous society that seems to consist mainly of white zombies waving flags.

And wearing yellow ribbons.

The best image I saw in the past couple of months was out in SF at The Writer’s Conference. I was down in the Tenderloin District sitting in a coffee shop and outside the window this hideous fucking pile of rags was walking around. You couldn’t tell what gender it was, totally fucked up red scaly arms hanging out the sides and a rag turban so you couldn’t see the face. It was someone who was obviously suffering. And attached to its chest was this HUGE pristine yellow ribbon. It’s time like that when I really feel like I’m going to lose it. Here is a person who is obviously human waste to this society and yet they’ve bought into war fever.

Do you attribute that mainly to the media?

I think an enormous amount should be attributed to the media. It’s denial, it’s ignorance, it’s weird misplaced hope. People don’t want to see how horrifying things are and are rapidly becoming. Sometimes I feel like I’ve been dropped from another planet because the denial is so severe. I’m just amazed all these starving people aren’t rampaging. People’s tolerance for physical distress is unbelievable.

Speaking of the media, explain your myth of the one-tribe nation.

The best context to place that in is what we get in the media. The generic upper and upper middle class group information/illusion fed us X number hours a day. The information apples to a mythic ‘general public’ and that is used by politicians and fundamentalists and anyone trying to set a particular structure in place and have it enforced morally or otherwise by institutions. It’s this myth that there’s one generic public that is totally untrue. Once you deal with people that myth breaks down.

In Close to the Knives you muse as to why more people don’t go completely berserk. What do you think pushes them to the brink?

I certainly have my moments where I feel if I witness one more thing I have the capability of crossing over a line and the only thing stopping me is that I don’t have access to weaponry. When I see some savage asshole on TV making proclamations about the epidemic, acting like the amount of death that has taken place is acceptable or of no concern or that the virus has or moral code or sexual orientation or whatever.

Or the racist fact that it’s been completely ignored in Africa.

Have we really gotten any information about AIDS in the past 10 years? People still laugh and make “who doesn’t know how to use a condom’ jokes on talk shows when using a condom is mentioned. But most people don’t know how to use a condom in a way that will keep a virus or STD from breaking through. We’ve never had any of that information blatantly outlined. I just throw up my hands. Come on, it’s 1991.

The anger in your book comes from frustration and also isolation. Do you think the level of frustration in this country makes people ready to revolt, but the level is isolation makes that impossible?

Given the power structure of this country I have no doubt that if there was a genuine civil war the government would have no qualms about shooting us all down in the streets. Look at the laws now being passed by The Supreme Court…that coerced confessions are okay and admissible in court. I can’t believe it. Cops can beat the shit out of you, make you confess to things you haven’t done and that’s acceptable in court. Our civil liberties are disappearing rapidly. I’d be overjoyed to see a civil war in this country; at least it’s a reaction that breaks through the apathetic field. But in reality it’s hard to imagine what could make a major shift. The only thing I’ve been about to come up with is other countries uprising to break the controls of this government.

True, there’s such a push here to be a good little citizen.

I was talking to a friend of mine and he and his boyfriend had come out to their respective parents and he got a letter from some woman who knows them and she sent a list of things they shouldn’t do in public if they want to make themselves acceptable as a couple. He read me the list and it was so outrageous. It’s the heterosexual nightmare of what other desire is. Squash diversity or alternate desire. Acting in prescribed notions of what identity should be is a joke.

In the book there’s a tension between restriction and freedom. How can a person act freely in a restrictive society?

People choose different paths; many unfortunately, are extremely self-destructive. You can do drugs to attempt to shift it but it never physically removes you from those restrictions. The landscape of this country is so controlled. What is freedom at this point? My frustration comes from wondering how one achieves any sense of freedom. Just about any activity – physical, mental, sexual – is slowly being controlled or hampered. I foresee a time when certain books and ideas will just be banned. There are a lot of people who believe all our methods of communication should be shut down or outlawed.

What do you think of outing?

One of the biggest problems is that I look at things from 12 different angles. When it’s somebody who’s actively destructive towards the gay community and who is in a position of power to effect laws etc. and they hide the fact that they’re a homosexual or lesbian I say “Out them”. It’s a complicated psychological process for people to come out. To out people merely because they’re not being verbal and outspoken about their desire — It can really do a lot of damage emotionally and psychologically if they’re not prepared. Personally, I had to work through certain things before I finally realized that society had no right to deny my feelings. I’m mixed on outing. It sounds wishy-washy but I think it’s an incredibly complex issue. The bottom line is if everyone came out life would change drastically because the power would be so evident. I wonder what it’s like for teenagers now. I don’t think it’s any easier culturally, but there is a much more visible system of support.

You mentioned realizing you were gay around 9. What happened for you?

My mother had custody of us and she put us in some kind of weird home with some psychotic woman and a whole bunch of other kids and somehow my father kidnapped us out of there and spirited us around in parts of Michigan to the farms of different relatives. When I was about 8 and a half brother, my sister and me contacted my mother to live with her in New York and after that the family just fell apart really quickly. By the time I was 9 I started having sexual experiences because I lived not far from Times Square and I practically lived in the movie houses because they were cheap cheap movies. I inadvertently tapped into this whole subculture and learned about hustling. I started running away from home periodically for different lengths of time and ended up living on the streets sometime in my mid teens. I came close to dying there. I was a walking skeleton and had no access to any kind of healthcare. I remember at 17 trying everything I could in terms of city agencies and not being able to obtain health anywhere. Eventually I got off the streets when some guy picked me up in Times Square who let me live with him for a month in this cheap apartment in that area. He was an ex con man. He worked as a counselor with fake degrees at a halfway house for ex-cons. He got tired of me being around because I was always stealing animals from pet shops and I turned his place into a zoo…giant African frogs and lizards and turtles. It was something I just always did as a kid. I used to steal alligators out of Macy’s and let them go in Central Park Lake thinking they were going to eat ducks and survive. I didn’t realize issues like winter. Anyway, this guy got tired of me and pretended he found me on street and took me to a halfway house. They took a look at my background and realized that if they didn’t let me in I’d eventually be there as an ex-con. Once I got into this house it was the first chance I really had to try and pull everything back together. I’d always tried to do some writing and drawing and once I got off the streets I just started exploring it more and more.

You’ve described your art as ‘fragmented mirrors’ of what you believe the world to be. Does that accurately describe Close to the Knives as well?

Absolutely. I had this conversation with my sister a couple years ago. I was talking to her about my work and she said, ‘You like to shock people’ and I said, ‘Look, that’s not what I try to do at all, this is really how I see the world.” People have this idea that I do certain things to provoke certain responses. Well on one level, sure, great, if I can provoke something. But it’s literally what I see and what I experience in the visual work, which has it’s own language, as well as the written work. It’s fragmentation and I think we’re all experiencing it but some people seem to be able to put up blinders and focus on very limited or small or specific things in order to make it through without experiencing the weird horror of what’s happening.

What would your reaction be to being called the conscience of the epidemic?

Well…there’s a lot of odd stuff that gets tossed towards me. One of my intentions with the book was to deal specifically with my own structure, my own sense of perception — visual or otherwise. If something I write or say encapsulates feelings that are out there — great. But the people I have the most respect for in ACT-UP, for example, aren’t generally the people with the greatest visibility. For me it’s the lesbian waitress from NJ who’s on her first action with her lover who’s scared to death and the two of them are about to place themselves on the line of being arrested for the first time in their lives. I have an unbelievable respect for people like that because they’re dismantling this illusion of law – of what law is and what law is intended to do. Quiet, anonymous people doing things that are confrontational for them. My response is that those people deserve the respect.

Thanks David, your book is amazing. It’s been great talking to you.

Thanks Owen, be well.

Photo ©Grover Sales

Photo ©Grover Sales