Marlon T. Riggs

MARLON T. RIGGS

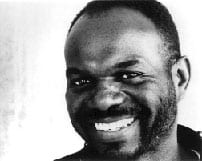

Before his death in 1994, African-American filmmaker, educator and poet Marlon Riggs forged a position as one of the more controversial figures in the recent history of public television. He won a number of awards for his creative efforts as a writer and video producer. His from theoretical-critical writings appeared in numerous scholarly and literary journals and professional and artistic periodicals.

His video productions, which explored documentary various aspects of African-American life and culture, earned him considerable recognition, including Emmy and Peabody awards. Riggs will nonetheless, be remembered mostly for the debate and contention that surrounded the airing of his highly charged video productions on public television stations during the late 1980s and early 1990s. Just as 1990; art-photographer Robert Mapplethorpe’s provocative homoerotic photographs of male nudes caused scrutiny of government agencies and their funding of art, Marlon Riggs’ video productions similarly plunged public television into an acrimonious debate, not only about funding, but censorship as well.

Riggs’ early works received little negative press. His production, Ethnic Notions aired on public television stations throughout the United States. This program sought to explore the various shades of mythology surrounding the ethnic stereotyping of African Americans in various forms of popular culture. The program was well-received and revolutionary in its fresh assessment of such phenomenon as the mythology of the Old South and its corresponding caricatures of Black life and culture.

The video Color Adjustment, which aired on public television stations in the early 1990s, was an interpretive look at the images of African-Americans in fifty years of American television history. Using footage from shows like Amos ‘n’ Andy, Julia, and Good Times, Riggs compared the grossly stereotyped caricatures of Blacks contained in early television programming to those of recent, and presumably more enlightened decades.

By far the most polemical of Riggs’ work was his production, Tongues Untied. This Art fifty-five minute video, which “became the center of a controversy over censorship” as reported The Independent in 1991, was aired as part of a series entitled, P.O.V. (Point of View), which aired on public television stations and featured independently produced film and video documentaries on various subjects ranging from personal reflections on the Nazi holocaust to urban Documentary street life in contemporary America.

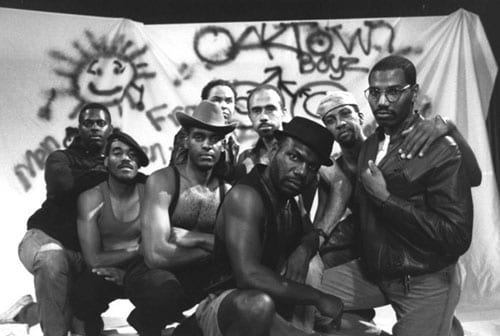

Tongues Untied, is noteworthy on at least three accounts. First, Riggs chose as his subject urban, African-American gay men. Moving beyond the stereotypes of drag queens and comic-tragic stock caricatures, Riggs offered to mainstream America an insightful and provocative portrait of a distinct gay sub-culture–complete with sometimes explicit language and evocative imagery. Along with private donations Riggs’ had financed the production with a $5,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), a federal agency supporting visual, literary and performing artists. News of the video’s airing touched off a tumult of debate about the government funding of artistic creations that to some were considered obscene. While artists argued the basic right of free speech, U.S. York government policy makers, especially those of conservative bent, engaged in hotly contentious debate regarding the use of taxpayer money for the funding of such endeavors.

The second area of consternation brought on by the Tongues Untied video concerned the area of funding for public broadcasting. The P.O.V. series also received funding from the Endowment, in the amount of $250,000, for its production costs. Many leaders of conservative television watch-dog organizations labeled the program as obscene (though many had not seen it). Others ironically heralded the program’s airing, in the hope that American taxpayers would be able to watch in dismay how their tax dollars were being spent.

Lastly, the question of censorship loomed large throughout the debate over the airing Tongues Untied. When a few frightened station executives decided not to air the program, the fact of their self-censorship was widely reported in the press. As mentioned, Tongues Untied was not the first P.O.V. production to be pulled. Arthur Kopp of People for the American Way noted in The Independent “…the most insidious censorship is self-censorship…It’s a frightening sign when television executives begin to second guess the far right and pull a long-planned program before it’s even been attacked.”

Riggs defended Tongues Untied by lambasting those who objected to the program’s language and imagery by stating in a 1992 Washington Post interview, “People are far more sophisticated in their homophobia and racism now…they say ‘We object to the language, we have to protect the community’…those statements are a ruse.”

Tongues Untied was awarded Best Documentary of the Berlin International Film Festival, Best Independent Experimental Work by the Los Angeles Film Critics and Best Video by the New York Documentary Film Festival. Marlon Riggs succumbed to AIDS in April 1994.

Before his death he began work on a production entitled Black Is, Black Ain’t. In this video presentation Riggs sought to explore what it meant to be black in America, from the period when “being Black wasn’t always so beautiful” to the 1992 Los Angeles riots. This visual reflection on gumbo, straightening combs, and Creole life in New Orleans, was Riggs’ own personal journey. It also unfortunately served as a memorial to Riggs. Much of the footage was shot from his hospital bed as he fought to survive the ravaging effects of AIDS. The video was finished posthumously and was aired on public televisions during the late1990s.

-Pamela S. Deane

Biography of Marlon Riggs

(1957 – 1994)

Marlon Riggs was known for making insightful and controversial documentary films confronting racism and homophobia that thrust him onto center stage in America’s “cultural wars.” Born in Ft. Worth Texas on February 3, 1957, Marlon graduated Magna Cum Laude from Harvard and received his masters’ degree from the University of California – Berkeley where he became a tenured professor in the Graduate School of Journalism.

Marlon’s first major work, Ethnic Notions (58 min, 1987), traces the evolution of the racial stereotypes which have implanted themselves deep into the American psyche across 150 years of U.S. history. The documentary received a National Emmy Award and other top film festival honors and has become a core audio-visual “text” in a wide range of courses.

But it was Marlon’s second major work, Tongues Untied (58 min, 1989), which catapulted him into the debate over public funding of the arts. This moving, highly personal, sometimes angry, always poignant documentary was the first frank discussion of the black, gay experience on television. Though acclaimed by critics and awarded Best Documentary at Berlin and other film festivals, its broadcast by the PBS series P.O.V. was immediately pounced upon by the Religious Right as a symbol of everything wrong with public funding for art and culture, particularly culture outside the mainstream. Riggs had received $5,000 from an National Endowment for the Arts’ regional re-granting program (now eliminated) and P.O.V. had received both NEA and Corporation for Public Broadcasting funding.

The Christian Coalition edited a highly sensationalized seven- minute clip from the film which they sent to every member of Congress. Senator Jesse Helms was point man for the chorus of denunciation. In a telling Freudian slip, he invariable referred to the film as Tongues United. Then Patrick Buchanan re-edited a 20-second clip from the film (a blatant copyright infringement) for a sensationalized TV ad “hit piece” blasting the NEA during the 1992 presidential primary.

Marlon responded with an Op Ed in the New York Times entitled “Meet the New Willie Horton” which recalled the notorious race- baiting ad George Bush himself used in the 1988 election. “The insult,” Riggs wrote, “extends not just to blacks and gays, the majority of whom are taxpayers and would therefore seem entitled to some means of representation in publicly financed art. The insult confronts all of us who witness and are outraged by the quality of political debate.”

It was perhaps inevitable that Marlon would become a lightning rod in this fight since he was an outspoken activist for a more diverse and inclusive media. In 1988 he spoke before a U.S. Senate Committee as part of the successful campaign to create the Independent Television Service (ITVS) supporting controversial, independent voices on public television. Expressing his vision of a more democratic, more inclusive television, he testified, “ITVS is supposed to shake you up, to address areas of deep taboo no one is willing to talk about, to give voice to communities which have been historically silenced. America needs to realize the value of having a communicative institution designed to challenge us and upset us. There is value in doing something more than making culture answerable to the marketplace.”

Marlon’s own next major work, Color Adjustment (86 min, 1991), challenged television itself. It traces over 40 years of the representations of African Americans through the distorting prism of prime time television, from Amos ‘n’ Andy to Cosby. Color Adjustment garnered television’s highest accolade, the George Foster Peabody Award, among other awards. That same year the American Film Institute granted Riggs their Maya Daren Lifetime Achievement Award.

Marlon Riggs’ final film, Black Is…Black Ain’t (86 min, 1995), is an outstanding example of the kind of committed television programming he struggled to support all his life. It wasn’t easy. While in production Marlon maintained his teaching position at U.C. Berkeley, took on public speaking engagements, and continued to write. All the while, the HIV virus was ravaging his body. Hospitalized by kidney failure and other ailments, he continued to direct – even appeared on camera – from his hospital bed and the film gradually took on a more personal tone as he got sicker.

Marlon finally succumbed to AIDS April 5, 1994. He was 37 years old. Black Is…Black Ain’t was completed by his co-producer Nicole Atkinson and editor / co-director Christiane Badgely from the footage and notes he left behind. Marlon is survived by Jack Vincent, his life companion of 15 years.

Towards the end of Black Is…Black Ain’t Marlon looks up at the camera from his hospital bed and says, “As long as I have work then I’m not going to die, cause work is a living spirit in me – that which wants to connect with other people and pass on something to them which they can use in their own lives and grow from.” Marlon Riggs’ tireless and caring spirit inspired many. We hope you too have been able to take nourishment from his last work, Black Is…Black Ain’t, and will help pass on Marlon’s critical eye and warm embrace.

Tongues Untied

by Alex Castro

Tongues Untied (1989 USA 55 mins)

Source: CAC Prod. Co: MTR Production

Prod, Dir, Phot, Ed: Marlon Riggs

Scr: Riggs, Essex Hemphill

Alex Castro is the director of Filmoteca: Spanish and Latin American Film Society.

Identities are the names we give to the different ways we are positioned by, and position ourselves within, the narratives of the past. Stuart Hall (1)

Marlon Riggs’ short career (he died in 1994 aged 37) was remarkably productive across a number of fields. However, the chief focus of his work as media artist, essayist and teacher was the interrogation of the ways in which representations of race and sexuality determine personal and public reality.

As a video-maker he produced 8 works between 1987 and 1994. (2) Of these, Ethnic Notions (1987) and its sequel, Colour Adjustment (1993) encapsulate his central themes and concerns. Both videos examine the depiction of black Americans in popular American media. While the former looks at 19th and 20th century print media, Colour Adjustment surveys contemporary prime-time television. He maintained this focus on black America throughout his career and at the time of his death was working on Black Is . . . Black Ain’t, a semi-autobiographical video designed to explore issues of black identity. (3)

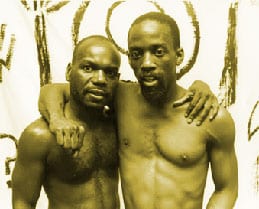

This particular mix of form and theme recalls the strategy of Tongues Untied (1989). Tongues weaves poetry, performance, popular culture, personal testimony and history in a complex pattern that emerges as an essentially personal statement. It presents the situation, politics and culture of black gay men using an intense mixture of styles ranging from social documentary to experimental montage, personal narrative and lyric poetry.

The idea for Tongues began as a video about the ‘Other Countries Workshop’, a New York-based poetry workshop for black gay men. As a non-poet, Riggs found himself drawn to their work because it spoke directly to his own experience. Through this, he became increasingly aware of feeling alienated by classical poetic form, which itself seemed to be speaking through and from the voice of a foreign and oppressing culture. Riggs’ focus shifted to a concern with the issue of voices and speaking, and how to do so from and about black gay culture.

Tongues speaks through a range of black, gay, and black gay cultural forms. The video is a melange that mixes the music of Billie Holiday and Nina Simone with the poetry of Essex Hemphill and Jospeh Beam; vogue dance and snap! expression (finger popping). The fictional Institute of Snap!thology, introduces us to snapping in a parody of ethnographic documentary. Riggs simultaneously celebrates the innovation and expression of the flamboyant gestures and acid wit of snapping, while also critiquing the positioning of black gay culture as an ethnographic subject. Similarly, he presents dance as an expression of cultural resistance, community building and cultural affirmation. With vogue, a dance style developed within black gay communities that animates the fashion photography of glossy magazines (such as the eponymous Vogue). Although subsequently popularized in white popular culture (think of Madonna striking a pose), Riggs makes the distinction of the dance as a performance for others (non-black gay men) and within the community. As the video cuts from vogue-dancers to a group of men dancing in Central Park he reiterates dance as a form of resistance and community.

Another key concern is the public expression of black homophobia and its relation to anti-gay violence. We see a montage-sequence in which church leaders decry gay relationships as an ‘abomination’, black political activists who consider black + gay as a conflict between loyalties, and we see excerpts from the ‘fag humour’ industry perpetuated by figures such as Eddie Murphy and Spike Lee. Riggs links these expressions to acts of violence in juxtaposing the violent rhythm of repeated insults with footage of the bashing of a black gay man. This is further emphasised in an autobiographical sequence, where Riggs’ personal testimony is framed by a series of abusive epithets: “fag, motherfuckin’ coon, punk”. Spat out at rhythmic intervals he underlines the interplay of racism and homophobia; experienced at one and the same time.

Through this personal testimony Riggs draws in secondary audiences unfamiliar with the black gay experience. As he recounts his experiences of bullying as a teenager, we recall our own adolescent doubts and anxieties. Yet, while many sympathise with the adolescent facing hostile schoolmates, the compounding of racism and homophobia call upon a leap of imagination for many non-black gay viewers.

However, although Riggs’ voice is central to the video, it appears as one voice among many. The many other voices we hear and see in the film create a sense of a dialogue that unfolds, rather than a singular, ‘tell it like it is’ argument. This dialogic mode of address brings the viewer into a direct relationship with the stories and individuals present in the video. Through this strategy, Riggs’ does not appear representative of black gay experience. Rather he speaks from the specificity of his own experience, which, because of the presence of other voices and stories, is not generalized or typified as the norm.

It is perhaps his dialogic strategy and interrogation of identity that distinguish Riggs from his American contemporaries. While there exists similarities and parallels with the work of other black American independent film-makers such as Spike Lee and Julie Dash, perhaps Riggs is closer to the black gay British film-makers and intellectuals such as Isaac Julien, Pratibha Parmar, Essex Hemphill, Kobena Mercer and Rotimi Fani-Koyde. As Riggs stated, “Taken as a group, we do not subscribe to notions of artistic effort for the sake of delighting the eye. Rather, our work addresses issues of identity, selfhood and nationhood in an effort to interrogate received notions of who we are.” (4)

© Alex Castro April 2000

Endnotes

1. quoted in Kobena Mercer, “Black Gay Men in Independent Film”. CineAction 32 (1993): 53.

2. These are: Ethnic Notions (1987), Tongues Untied (1989), Anthem (1990), Affirmations (1991), Non, Je Ne Regrette Rien (1992), Colour Adjustment (1993), Black Is…Black Ain’t (1994). 3. Janet K. Cutler “Marlon Riggs: Identity and Ideology”. Persistence of Vision (1995): pp65-66.

4. Cutler, pp72-73.

MARLON RIGGS

Born in Ft. Worth, Texas, U.S.A., 3 February 1957.

Graduated from Harvard University, magna cum laude, B.A. in history 1978; University of California at Berkeley, M.A. in journalism 1981. Taught documentary film, Graduate School of Journalism at the University of California, Berkeley from 1987; produced numerous video documentaries, from 1987. Honorary doctorate, California College of Arts and Crafts, 1993. Recipient: Emmy Awards, 1987 and 1991; George Foster Peabody Award, 1989; Blue Ribbon, American Film and Video Festival, 1990; Best Video, New York Documentary Film Festival, 1990; Erik Barnouw Award, 1992. Died in Oakland, California, 5 April 1994.

TELEVISION DOCUMENTARIES

1986 Ethnic Notions

1989 Tongues Untied

1992 Color Adjustment

1992 Non, Je Ne Regrette Rien (NoRegret)

1994 Black Is…Black Ain’t

PUBLICATIONS (selection)

“Black Macho Revisited: Reflections of a Snap! Queen.” Black American Literature Forum (Terre Haute, Indiana), Summer 1991.

“Notes of a Signifying Snap! Queen.” Art Journal (New York), Fall, 1991.

Grundmann, R. “New Agendas in Black Filmmaking: An Interview with Marlon Riggs.” Cineaste (New York), 1992.

FURTHER READING

Becquer, M. “Snap-Thology and other Discursive Practices in Tongues Untied.” Wide Angle–A Quarterly Journal of Film History, Theory and Criticism (Athens, Ohio), 1991.

Berger, M. “Too Shocking to Show.” Art in America (New York), July 1992.

Corey K., and Alexander Doty. Out in Culture: Gay, Lesbian, and Queer Essays on Popular Culture. Durham, NorthCarolina: Duke University Press, 1995.

Harper, Phillip Brian. “Marlon Riggs: The Subjective Position of Documentary Video.” Art Journal (New York), Winter 1995.

Maslin, Janet. “Under Scrutiny: TV Images of Blacks.” The New York Times, 29 January 1992.

Mercer, Kobina. “Dark and Lovely Too: Black Gay Men in Independent Film.” In, Gerver, Martha, with others, editors. Queer Looks: Perspectives on Lesbian and Gay Film and Video. New York: Routledge, 1993.

Mills, David. “The Director with Tongue Untied; Marlon Riggs, A Filmmaker Who Lives Controversy.” Washington (D.C.) Post, 15 June 1992.

Prial, Frank J. “TV Film About Gay Blacks is Under Attack.” The New York Times, 25 June 1991.

Tongues re-tied? Filmmaker Marlon Riggs speaks for a group mainstream America would prefer to erase. – August 12, 1991

Scott, Darieck. “Jungle Fever? Black Gay

Identity Politics, White Dick, and the Utopian Bedroom.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies (Yverdon, Switzerland), 1994.