Harmony Hammond

Harmony Hammond is Guggenheim fellow and recipient of two NEAs, is an artist, art writer, and independent curator who lectures, writes, and publishes extensively on feminist and lesbian art, queer art, and the cultural representation of “difference.” She co-edited the ground breaking “Lesbian Art and Artists” issue of Heresies magazine in 1977 and curated the first exhibition of lesbian art in New York in 1978. Recently she curated “Out West” for Plan B Evolving Arts in Santa Fe. Her work was included in the 1995 exhibition “In A Different Light: Visual Culture, Sexual Identity, Queer Practice,” at the University of California, Berkeley.

In the Succeeding Silence

By Paul Eli Ivey

I look for moments of engagement in art and life. Art makes connections. It is a tool. It is a weapon. It makes the strange familiar and the familiar strange. Both [art and the martial arts] are about occupying and negotiating space, moving through it, with an awareness of how you affect the world around you, moving with intent and ethical responsibility. Harmony Hammond, “M(art)ial Engagements” 1998 Harmony Hammond, prominent first generation feminist artist, activist, curator, celebrated author, professor, martial artist and volunteer firefighter, has produced a new and powerful body of work that is a sophisticated restatement of her continued engagement with the relationships between form, process and meaning in painting and sculpture. These concerns are wedded with her commitment to explore and intensify personal and cultural symbols of the gendered body, now made more vulnerable when viewed through the lens of tragic lost innocence, fused from the crucible of September 11, 2001.

In 2000, Hammond’s pioneering Lesbian Art in America, A Contemporary History, was published by Rizzoli International Publications. This award-winning book testifies to a career-long interest in the problems of lesbian self-representation in a patriarchal society where images of women are still primarily controlled by men and their bodies objectified by male desire. Hammond’s book explores what it is to “see”and represent as a gendered, lesbian subject. This topic is dramatically reframed in “Dialogues and Meditations” through the use of both traditional art materials and physical signifiers embedded in western myths and fairy tales concerning female sexual power and sexual transgression. The works provide insights into the psychic mechanisms that inform the ways in which we represent and view our sexuality and also reveal our primal fears of loss and vulnerability.

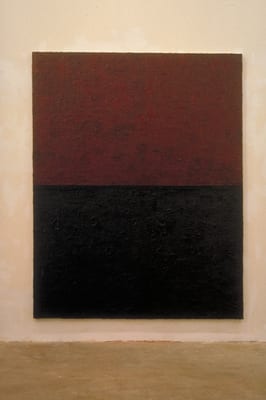

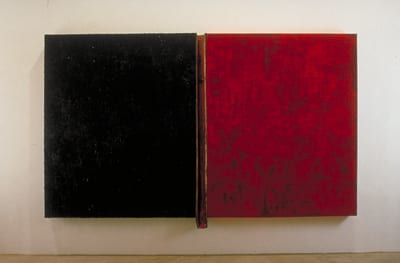

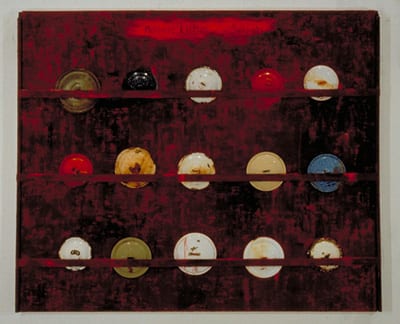

Hammond always uses symbolic substances and images, but often in very abstract ways that are not immediately apparent to the promiscuous gaze, seeking simple erotic pleasure across the surfaces of bodies and objects. Her formal, abstract works use paint as an expressive topographical substance, exploring notions of connection, fragmentation, insertion, intervention and transgression, transmuting the modernist painting field into the body-as-site. In “Rupture,” for example, the thick layering of dense paint, juxtaposed to transparent alizarin crimson, is connected/separated by a bloody metal gutter that can be read as a trench bisecting two fields, or as a metaphor for the body’s circulatory system. In either case, the gutter, meant to collect and carry life fluids, is now dried up. The painting becomes a dialogue of human relationships as well as formal ones.

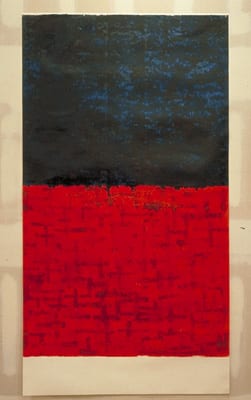

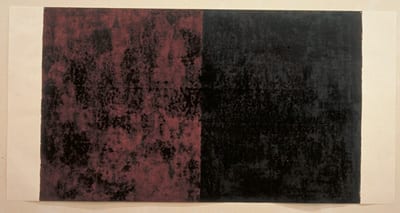

Hammond’s paintings are grounds for a meditation on encounter and balance, on sacrifice and survival. She builds up lush, impasto works of great presence and weight, where the eye rests on thick surfaces without cognizance of brushstrokes, only to look through as the paint exudes and reveals in its depths the bleeding bodies underneath, particularly apparent in the mixed media piece “Meditation.”

Some paintings balance the tensions between thick paint and thin, revealing gaps that suggest psychic spaces realized but not actually seen. These are suspended in a liminal space that oscillates in our field of vision, never materializing into an image, but found in the often raw and uncanny feelings that are created by the great physicality and scale of the works and their suggestion of bodily substances. To Hammond, the painting surface and the perimeter of the work are both edges that mediate between the piece and the viewer, setting up a dialogue between them.

The suturing of one canvas to another by way of an architectural referent reveals the multivalence of Hammond’s use of remnants and fragments from the world. Hammond utilizes these and other elements as surrogates that condense many possible meanings, even apparently disparate ones. For example, the rusting gutter and roof ridge, like the corrugated tin, linoleum, and buckets in her past work, are materials that denote their original functions and meanings, but also suggest other readings: the labor of construction, the domesticity of the home, survival in difficult times, and abandoned farms. Her use of straw and latex rubber also suggests the body. The paintings become metaphors for the private and sexual body, the gutter and roof ridge are linked as elements in-between, where the encounter of equal partners sometimes causes friction and blood to be shed. These paintings provide the theoretical templates that help us understand Hammond’s fascination with suggestive materials like hair, skulls, and hemp.

***

Hair is a potent personal and cultural symbol and one that Hammond has returned to throughout her career. She has used actual human and animal hair, materials such as thread, straw and hemp that reference hair, as well as images of forms typically constructed of hair, such as the braid and the pony tail. In the early 1970s in New York City, where she began her martial arts training, started to exhibit her feminist art work, and came out as a lesbian, Hammond used human hair in numerous pieces, such as her hair blanket, a hair dress (later destroyed), and a series of small hair bags representing individual women in her feminist art group. In 1974, after a devastating fire in her Bowery loft, she cut off her long hair. Her new crew cut was a cleansing, a visual sign of change in her life, and a proclamation of her gender and lesbian sexuality. Later, in the 1990s, Hammond combined latex rubber with her own hair and the hair of her daughter or friends, to suggest landscapes of gendered and sexualized bodies. The braid and the pony tail also took on a life of their own as personified characters: the braid relating to an integration of mind, body, and spirit; the stylized ponytail becoming a flirtatious, sexualized persona.

Many of the pieces in this exhibition have literal and symbolic references to hair, as do many classic myths and folktales about female sexuality, such as the Medusa and Rapunzel stories. As Hammond reminds us in her 1984 book Wrappings, Essays on Feminism, Art, and the Martial Arts, when the beauty and power of the feminine are combined in myth, the result has been called “a monster, a vampire, a witch, a lesbian, a mad woman, Medusa, a woman gone wild.” (1)

Hammond’s first etching in art school was a head of Medusa. The image does not appear literally in this exhibition but the signifying elements of the Medusa abound. Hammond includes bronze heads in three of the works, taken from life casts of her own head that were then reworked in their wax states, but not as self portraits. These she juxtaposes or combines with real hair or hair-like braids.

The mythic Gorgon Medusa, originally a woman of such beauty that she competed with the goddess Athena, was known for her luxurious and attractive hair. When she was ravished out of wedlock by Poseidon, disguised as a horse, in chaste Athena’s temple, the goddess punished this transgression by turning her plaits into snakes and giving her the power to turn any would-be lover or enemy who gazed upon her to stone. Perseus beheaded Medusa, and the primal energy of her power was subjugated and constrained: her mighty head was used in battle and her blood to either poison the living or to reanimate the dead. Gorgons have long symbolized female sexual energy and the fear that men have for this creative, animating power.

The two dark bronze female heads of “Unspoken,” beautifully patinated, are sleeping muses that at first glance remind us of Brancusi’s passive ovoid shapes, but their reworked surfaces are rough and violated. Their eyes and mouths are closed but they are not mute: they confront and engage us in wordless, uncanny feelings. They are uncleanly decapitated and subtly bleeding. The gash in each reveals a dark emptiness, as if all inspiration and power has seeped away. Only the shorn hair remains. The heads are juxtaposed to a single braid of human hair. Disembodied, it is a free-floating signifier of power, cut off from its source. Medusa is both bald and beheaded, doubly signifying loss of innocence and a sexual disempowerment where female sexuality becomes a blindspot that cannot be simply seen or easily represented by the male gaze. This opens up a powerful space for lesbian desire, for what the male gaze cannot see or control becomes lesbian.

In the Rapunzel story, the powerful connection between two women is hair, a lesbian theme finely developed in American confessional poet Anne Sexton’s “Rapunzel.”(2) Rapunzel, given to a witch upon birth, was shut up in a tower at puberty to keep her safe from the world. She was available only to the witch, who visited her daily by climbing up the great lengths of her beautiful, golden hair. A prince who dared to seduce Rapunzel to ride away with him on his horse was confronted by the witch, and in fear he leapt from the tower into a thicket of brambles that blinded him. Rapunzel’s hair was cut off and she was banished to the desert. Walking endlessly the prince finally found Rapunzel, whose tears of joy touched his eyes, healing them. In this version of the story, Rapunzel’s loss of hair indicates disconnection and banishment until she rediscovers hetero-normative desire. The story also suggests, as does the Oedipus myth, that the power of female desire blinds males, who are therefore unable to visibly represent it. The talisman of hair in “Unspoken” reconnects us with the power of female desire.

The notion of sacrifice itself is an important framework for understanding many of the works in this exhibition. Sacrifice is fundamentally a search for connection or reconnection with the sacred. As George Bataille suggests, that which is sacrificed is no longer an object in the world but a conduit, intimately connected to a realization of the all pervading, indwelling immanence of the sacred: of life’s continuity in the face of death.(3) The hair, once a part of a human being, has been cut off and sold for economic reasons. Hammond reframes this commodification as an element that has the power to connect us to myth, to continuity, even to the sexual life with the development of the gendered psyche. This dead braid and the heavy, dead heads, actually affirm a life beyond the commodity, a life where the passionate struggle between self-understanding and creativity is the key to an intimate blending with the sacred and sexual.

As psychoanalytic specimens, the hair and heads also remind us of body parts displayed as artifacts in an anthropological or medical museum. Strangely living and dead at the same time, they become the debris of the modern erotic unconscious, with its connection to the fear of death. Together, the unseeing, severed heads and the estranged hair produce a reaction that Freud called the uncanny, which summons up unconscious fears of castration and loss, of being cut off from what’s homey or secure. The surrealists were fascinated with the uncanny, and used the disruptive potential of the female mannequin as a surrogate for the male’s fear of castration, produced by seeing the woman as lacking and with the potential to cause his own lack. Man Ray, in particular, manipulated women’s eyes in his pieces to produce this anxiety at the level of the visible. But in “Unspoken” the eyes are closed: the space for representing women’s desire will not be simply visible and might often be hidden from the male gaze.

In “Untitled (head),” the decapitated head has been sheered off, as in public execution, reminding us that women in the public sphere have often been viewed as threatening to the gendered, patriarchal order. Symbolically, decapitation is also a displacement of castration anxiety: “Off with her head!” The guillotine produces martyrs for the revolution, and the head becomes a symbol of the act of transgression, recalling the severed warrior head of Medusa taken into battle. The head appears burned and scarred, its eyes and mouth fixed open, the letter “L” incised into its forehead. Abandoned on a rusted iron dolly, it seems to whisper: sexual transgression is political subversion. The gaze here is petrified, and is another image of Medusa immolation as the face looks beyond the death of self and joins with others who have been sacrificed for the crime of having seen and spoken as a woman. We fear dead things and becoming a dead thing, but we know that death connects us. We avert our eyes in remembrance of those killed for simply being women or outlaw women.

***

“Speaking Braids” is an uncanny combination of elements, with its elevated and disembodied head, braided hemp hair, and squarish piece of thick wax . While the plaited head echoes the beauty of antique korai figures, often said to represent a self- consciousness of the power accorded femininity in the archaic period before goddess myths were totally eclipsed, it is also cut off from the body. From its mouth a hemp braid springs to the ground, encircling a wax, book-like form. The fixed, impersonal eyes betray the fact that the vomiting form has been associated with feminine hysteria, symbolizing psychic conflicts suffered by women who refuse to marry. But it is also purging, as the braid is a tress of interwoven strands, a metaphor for the joining together of similar but disparate female voices, in the act of writing a book about lesbian art that is open-ended, suggestive, molded like wax but broken off, unfinished.

Hammond weaves and connects the strands, taking in inspiration, breathing out narrative. In Japanese Shinto hemp represents cleansing, purity and even fertility. It also represents the forbidden and the hidden as it is unduly associated with criminality in the West. Here it resonates with a perception of the importance of coming out with a public confession of one’s outlaw sexuality.

“Speaking Braids” is about the burden of representing other women’s voices and accepting this task, as well as about the necessity of speaking, as author and artist, with a gendered and sexed voice. We move from the woman as signifier of male desire and fear, to woman as the power broker, negotiating ways to creatively represent herself for herself with her own creative voice. Like the twelfth century Lady Godiva who knew that the ancient Greeks had held the nude body in great esteem as an object of pure beauty, and accepted her husband’s challenge to ride unashamedly naked through the town in return for a repeal on taxation. With her long hair braided about her head, she rode like a warrior, with great pride and dignity, impressing everyone with her perfect female body. So Hammond, as author, engages her audience in a public way, proclaiming the dignity of the powerful lesbian body through writing a book that was itself an act of resistance against cultural erasure. Authorship also provided Hammond with an oversight that fully informs her own work as a visual artist: that female energy and desire are agents of a fighting spirit not simply captured in pictures but felt as a powerful presence, as a raw essence, as a transformative and creative power that demands its own place within the masculinist site of modernist painting.

***

The paintings in this exhibition meditate on and interrogate the history of modernist painting since the rise of Abstract Expressionism. Hammond has been able to strike out into territory occupied by artists such as Robert Rauschenberg, Joseph Beuys, Eva Hesse, Anselm Kiefer, Bruce Nauman, Leon Golub and Kiki Smith, and in a way that makes use of abstraction, figuration, and symbolism. In the paintings, color combinations dialogue with each other at the central border while the outer edges of the surfaces are often irregular, with paint coagulating on the margins of the armatures, resisting the geometry of right angles. The paintings become bodies in tension and balance, competing and integrating with each other. Ancient classical medicine sought the balance of bodily fluids, called the four humors, which were associated with certain colors: blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile. Often blood-letting and induced vomiting were used to bring these humors back into balance. Metaphorically, Hammond’s paintings also deal with hot and moist colors as well as cold and dry ones. She seeks to balance these often erotically-charged elements, such as the dried and bloody crimsons next to deep and earthy blacks.

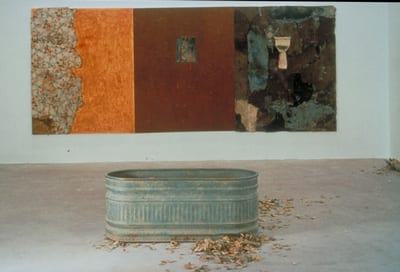

“Meditation,” the most ambitious painting in the show, is monumental in its solidity and symbolic resonances. Using the horse skull was risky for Hammond because skulls are over-determined symbols of the wild west and a well-known motif in the imagery of one of northern New Mexico’s most famous women artists, Georgia O’Keeffe. While the use of the horse image might come simply from living around horses (her house literally abuts a horse stable), this skull was carried to New Mexico when Hammond moved there from New York in 1984, and its importance as a symbol is far-reaching.

From the decapitated head of Medusa sprang the flying horse Pegasus, who was tamed by Athena and later caused the fountain of the muses to gush forth: thus Pegasus typified inspiration. The horse represents freedom of movement and escape, as well as the powerful force of female sexual desire, in the paintings of Rosa Bonheur and Romaine Brooks, two painters who were openly lesbian long before the liberation movements of the late 1960s‚ or the queer theory of the 1980s and 1990s. Adolescent girls’ fascination with horses has often been translated as displaced sexual desire: a theme explored in the work of contemporary lesbian artists Deborah Bright, Julia Kunin and Patricia Cronin. Earlier works by Hammond such as “Burden,” a weathered, workhorse collar atop a wounded straw field, and “The Dyke and the Diva,” a portrait of a relationship consisting of a skin of latex rubber, a braided lariat, and a worn leather riding whip, also referenced horses and sexuality.

In “Meditation” the encrusted, flayed surface, with its great, fiery energy bubbling underneath, is punctuated by a horse feeding trough, in which the violently ruptured cranium of a horse head hangs suspended. In the bottom of the trough is a residue of a leathery, flesh-like substance and tiny bits of straw. The holes in the trough are oozing. The nails that hold the trough in place pierce the painting, violating it and reasserting the surface as a body that bleeds. The altar-like arrangement of horse and trough suggests a sacramental sacrifice, ritually enacted. As Bataille puts it, the sacramental element of sacrifice, is the revelation of continuity through the death of a discontinuous being to those who watch it as a solemn rite. A violent death disrupts the creature’s discontinuity: what remains, what the tense onlookers experience in the succeeding silence, is the continuity of all existence with which the victim is now one. (4)

The equine symbol, which resonates with the ideals of our freedom of movement, inspiration, and sexual longing and fulfillment, thrown into stark relief last September, is powerfully positioned as a reminder of our personal connection to life’s continuity and our own fear of loss and even death. We grieve for those who have died needlessly; we grieve for that which has been sacrificed.

***

The works in this exhibition are not didactic and do not expose some underlying single truth of being, but are maps of meaning where fields, territories and borders are negotiated, personal and cultural symbols are deployed and left for us to feel, read and decode. To do the work that these works require is to explore the mechanisms of the creative female psyche representing itself and encouraging our interaction. These visual works are committed to establishing what Hammond calls “a true meeting of energies or an encounter with others” that the martial artist seeks on the path of spiritual realization.(5) They reveal a pathos sited on the fragility of our sexual bodies and yet they work to reconnect us to a very human and creative continuity that is powerful in its passion, hope, and connection to others.

Paul Eli Ivey, Tucson, Arizona, 2002

(1) Harmony Hammond, Wrappings, Essays on Feminism, Art, and the Martial Arts (New York: TSL Press, 1984), 89. (2) See Anne Sexton, The Complete Poems of Anne Sexton (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1981), 244-249. (3) See Georges Bataille, Theory of Religion (New York: Zone Books, 1992), and Georges Bataille, Erotism, Death and Sensuality (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1986). (4) Bataille, Erotism, Death and Sensuality, 82. (5) Harmony Hammond, “M(art)ial Engagements,” New Observations, 118 (Spring 1998), 8.